Leadership will be main problem in NFL's ongoing labor negotiations

Gary Roberts has witnessed a full spectrum of loony behavior while studying sports law for more than three decades.

A judge asking for a witness' autograph? Roberts, the Dean of the Indiana University School of Law and one of the nation's foremost experts on sports antitrust and labor issues, still speaks incredulously when recalling the time a judge leaned over his bench to ask for Don Shula's signature.

Congressional hearings packed for an athlete's testimony, then deserted when the real experts show up? Judges using nonsensical sports terminology, like running a full-court press to score a touchdown, to fit in with celebrities gracing their courtroom? They're among the dozens of examples Roberts remembers.

"Sports tend to make otherwise intelligent and thoughtful people turn into blithering gooneybirds," Roberts told a gathering of the nation's newspaper sports editors at a labor law workshop sponsored by the Indiana University National Sports Journalism Center in Indianapolis. "People do the dumbest things when sports are involved."

Such as threatening to shut down the immensely popular NFL when television ratings are setting records and revenues are soaring? Roberts has seen it before, and foresees the outcome like the cliché ending to a b-grade movie.

"Put it on your calendar," Roberts said before delivering his predicted end to football's labor strife. "It'll be about Sept. 8."

Seem a little quick for a labor dispute building off two hyped years of tough talk and stiff demands? It might be, if the storylines were truly the core issues. But in Roberts' view, they're mostly a smokescreen.

The real issue, he says, is about leadership.

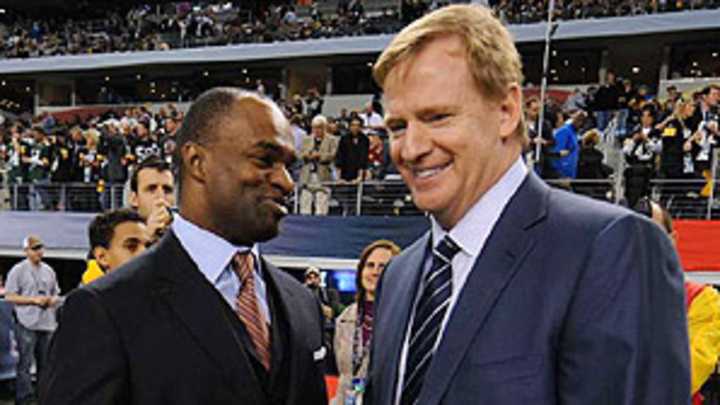

On one end of the table is Roger Goodell, the charismatic NFL commissioner who forged his early identity around getting tough on player conduct. Now, Roberts said, the commissioner who wasn't voted into his position by owners five years ago until the fifth ballot was cast, is looking to show owners that he can get tough with the union as well. Same goes for DeMaurice Smith, the football outsider and former Washington D.C. law firm partner who established a get-tough agenda after joining the union two years ago.

It's a sharp departure from the uneventful negotiations former union chief Gene Upshaw held with former commissioner Paul Tagliabue nearly five years ago. Owners decided they got hosed on that deal and opted out of the CBA in 2008, charging Goodell with delivering concessions from players. Smith dug in after taking over and led a stiff resistance.

Two men negotiating their first collective bargaining agreement. Two men who have no reason to trust each other yet. And two men whose constituencies expect a tough stand.

That's what this labor strife is about, Roberts said, not revenue splits, player health care and shortened careers brought on by longer seasons.

"We've got a leadership problem, in my judgment," said Roberts, the author of a widely used sports law casebook, "Sports and the Law." "You don't see deals done before absolute Armageddon is on the horizon when that's the way that the sides approach collective bargaining. What we've seen here is an issue where the leadership and the strongest elements within the constituency of the players and the constituency of the owners is insisting on toeing a very hard line, and they've sort of painted themselves into a corner. Neither side wants to blink first."

The rhetoric will continue, Roberts said. Tempers will heat up, fingers will point and name calling will grow offensive.

And just when it looks like hope is giving out, Roberts believes, the deal will get done.

Most likely by early September.

"When feet are held to the fire, you're going to see an agreement done," Roberts said. "There's just too much at stake not to."

But that doesn't mean things won't get legally complicated before settling out. Some possible outcomes Roberts believes could happen include:

Contention over union decertification: Reports have circulated for months suggesting that the NFLPA may elect to decertify in order to gain legal leverage in the event of a lockout. Roberts said a 1996 Supreme Court ruling (Brown v. Pro Football) prevents the union from bringing anti-trust litigation against the NFL as long as it remains certified by the National Labor Relations Board, but by decertifying the union the lockout could be viewed as an unfair labor practice.

The NFL would then contest the legitimacy of the union's decertification, Roberts said, claiming that it is only a smokescreen tactic by an organization that will recertify once negotiations are completed.

"Whoever has heard of a law that you can just turn on and off like a light switch?" Roberts said. "There are a lot of husbands out there who would love that deal. But that's what the union believes it can do, and it's not clear whether that would be effective."

The ruling for either side would significantly affect who holds the leverage in negotiations. But the union has one card in its pocket that could trump the owners' case.

Judge David S. Doty, friend of the union: Roberts said the union would file their anti-trust argument in Minnesota, where they eventually would get the case in front of U.S. District Judge David Doty, whose previous rulings have favored the NFLPA. Doty's rulings heavily influenced NFL labor negotiations in the early 1990s and helped produce the current CBA.

If Doty recognizes the union's decertification and allows anti-trust litigation to proceed, the legal entanglements could drag on for years, Roberts said. It's an unlikely scenario because the damage created would cost both sides significant amounts of money. But if it happened, Roberts said it may be the only scenario that could cost the NFL a full season.

"Because of all of this chaos going on, with the parties not really knowing how this is going to play out in court, you could end up with a situation where both sides judge that their legal position is stronger than it might actually be," Roberts said. "And that's the one scenario in which I could see the work stoppage lasting a lot longer past early September."

Decertification not guaranteed: Roberts doesn't believe decertification will be an initial tactic the union employs because of the risks involved. By decertifying, Roberts said a union stands to lose its influence over the players, control over benefits, such as pensions, and the ability to certify player agents. Some of that control can be difficult to regain if the players recertify the union.

"I think that the NFLPA will only decertify if they see it as a last resort," Roberts said. "But I think that could happen if the owners are holding firm, not making any concessions, they lock the players out and the players see the only way they're going to have a chance at salvaging the season without making huge concessions is to decertify. I think (under those circumstances) they will try that. It will be an unhappy day for them, but nevertheless, it's a tactic they may well see they have to use."

Lockout may not occur in March: While the owners are widely expected to lock out the players when the CBA expires on March 3, Roberts said the owners do not have to initiate the lockout immediately. Terms of the current CBA would continue until a new agreement is reached, and events such as the NFL Draft could continue unaffected.

But if the lockout doesn't begin immediately, Roberts said the owners will be forced to lock the players out if no deal is reached before training camps open because of a 1962 legal ruling (NLRB vs. Katz) that prohibits employers from changing labor terms under negotiation. So once players report to camps, the NFL owners would be forced to operate under the terms of the old agreement for another full season.