The painful existence of being a Browns fan

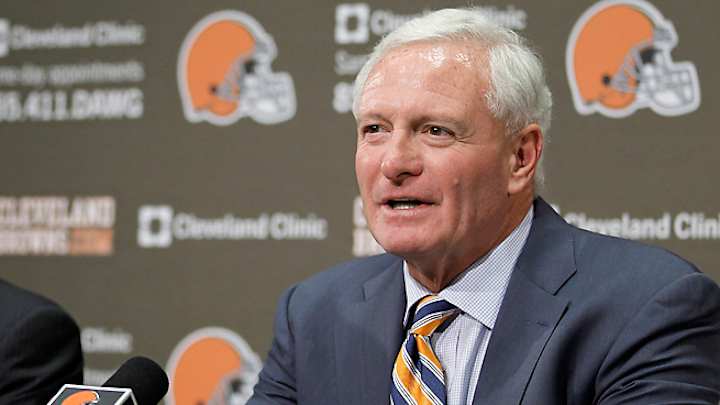

SI.com producer Paul Forrester is a Cleveland native and Browns fan. With the news that team owner Jimmy Haslam -- whose purchase of the team brought hope for the long-suffering fanbase -- is being investigated for fraud, we asked him to describe the familiar emotions of frustration and disappointment that come with being a member of the proverbial Dawg Pound.

For some, the fact that a team's owner is under investigation by the FBI would constitute an impending disaster. For anyone following the Browns, it's little more than a flower of frosting on a cake of disappointment the team has baked its fans for decades.

The ongoing fraud probe into Browns owner Jimmy Haslam's business practices at his chain of Pilot Flying J truck stops joins a long, disheartening list of failures by which Cleveland fans mark their interaction with pro football.

There's "Mike Phipps," the No. 3 overall pick of the 1970 draft, who threw for 40 touchdowns and 81 interceptions over the course of seven seasons quarterbacking the Browns.

There's "Red Right 88," the play called when quarterback Brian Sipe rifled an end-zone interception into the arms of Raiders safety Mike Davis in the final minute of Cleveland's 14-12 1980 AFC Divisional loss on a zero-degree day at home.

There's "The Drive," when John Elway led the Broncos 98 yards at the end of the fourth quarter to tie the 1986 AFC Championship Game at 20 before moving Denver 50 yards in overtime to set up an AFC title-clinching field goal.

There's "The Fumble," when Cleveland running back Earnest Byner undid the goodwill brought on by his two touchdowns in the 1987 AFC title game by fumbling away what appeared to be a game-tying touchdown into the hands of Broncos cornerback Jeremiah Castille with a minute and change left in the fourth quarter.

There's Bill Belichick, who worked out the kinks of his Hall of Fame coaching career by compiling a 36-44 record while also cutting local hero Bernie Kosar, who may have been past his prime but not past his popularity.

There's Art Modell, who, for all the good he did for the league, will be remembered in Cleveland for two things: firing team founder Paul Brown and moving the franchise to Baltimore when he couldn't reach a deal with the city to build a new stadium.

And that was all in the first incarnation of the Browns.

In the late '90s a construction effort took off, aimed at enticing suburbanites to go to Cleveland to shop, eat and maybe attend an Indians game at was then their relatively new stadium. The Browns hadn't been part of that effort, what with civic dollars tight and what money there was tied to the Indians' new park and a new arena for the Cavaliers. In not getting a seat on the urban renewal train, the Browns, in need of new revenue streams as much as any NFL team, left for the stadium dollars promised in Maryland.

At that point, the Browns transformed from a football franchise into a ticking clock. Literally. When Modell moved the franchise to Baltimore, a huge public outcry earned Cleveland an expansion team with the Browns' history attached. But three years would pass before the NFL returned to the city. In its place was stadium construction, ticket waiting lists and a countdown clock, located a half mile from the new stadium site in the middle of Tower City, a newish, downtown mall part of that development.

Unlike the rest of Cleveland, though, the Browns didn't need renewal to attract visitors in the first place. The franchise was the medium through which everyone in northeast Ohio could communicate, no matter how many trough urinals backed up at the stadium or how long you had to wait in line for a beer. Sports fans tailgating at the sprawling municipal lot outside Cleveland Stadium or single mothers who didn't watch a minute of football Sunday all knew whether the Browns had won or lost, who had starred and who had disappointed. That wouldn't help on the balance sheet, but you'd like to think it would have been enough to keep the team afloat until the economic realities of the NFL left no choice but to build a new stadium when feasible.

It wasn't. And with the team's departure came unanswered questions about being a fan. The team hadn't appeared in a championship game since 1964, and the sadness with which each season ended played a pivotal role in developing the fatalistic nature many from Cleveland (OK, at least me) possess. But there wasn't anything embarrassing in coming up short when the effort appeared clear. You can live with disappointment, learn to fight through, if the effort is there. But when the team gave up and packed up, what was left for its fans to hold?

The promise of a new regime? An expectation that the new Browns couldn't be as heartbreaking as the old ones?

Wrong.

Tim Couch, the new team's first draft pick, showed they could draft a quarterback almost as disappointing as Phipps at No. 1 overall.

In 2003, the new Browns also showed they could choke away a game as easily as their predecessors. A 33-21 lead in a divisional playoff game against the Steelers evaporated into a loss in the final seven minutes when Tommy Maddox led a Pittsburgh comeback and Browns receiver Dennis Northcutt dropped a drive-extending, first-down pass with about two minutes to go.

And now comes Haslam, who rode in on a billion-dollar white horse to save the team from an ownership family that changed front offices as if they were car leases. And though Haslam had long been a part owner of the hated Steelers, though he had no ties to Ohio and though he bought the team because it was available more than because he wanted the Browns, Cleveland fans bought in. That's what a 73-151 record since the team returned to the NFL will do to a fan base.

But before even drafting a player, Haslam has taken his place in that long line of Browns' disappointments. Maybe the accusations are false. Maybe he didn't know about a scheme to defraud trucking companies of gasoline rebates so his company could pad its bottom line. But the FBI doesn't target people by accident for the most part. And with the federal government involved, the case is sure to drag on, carrying with it countless stories about what Haslam knew and didn't know. More importantly to Browns fans, what will Haslam's role with the team will be moving forward? Eddie DeBartolo didn't survive (on NFL terms) his run-in with the feds, and he had five Super Bowl rings; will Haslam?

By now, the standard by which Clevelanders judge their teams isn't high. Maybe a .500 record would be a start? Hell, 10-6 and your name will be on the stadium. Stale bread and water is quite a feast to someone in prison. And though Browns fans aren't in prison, we're certainly not free of a past, and present, that tests one's reason for being a fan. That countdown clock may be gone, but the team never really came back, not the way it was, not yet. But we'll keep waiting.