What’s Lovie Smith Doing on Sunday?

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie Ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. —Ralph Ellison, from “Invisible Man”

* * *

LAKE FOREST, ILL. — It would be rude to turn up on Lovie Smith’s doorstep without bringing something, even if that something is little more than a preconceived notion. Smith’s enduring image while coach of the Chicago Bears was that of an arms-folded, thousand-yard staring, robotic-speaking sphinx—John Amos without the Good Times. And even though it’s been 10 months since the Bears fired Smith and effectively killed off a character that never meshed with the Windy City’s cast of mythically outsized coaching personalities, surely some version of that sideline sphinx waited inside this stately brick house in this northern Chicago suburb on this unseasonably bright and warm October Sunday.

But another figure, as tall and bald and beefy as the coach of lore, rises from an overstuffed living room couch dressed in a black T-shirt and dark jeans. His arms are spread out in welcome. His eyes glisten with excitement. He laughs sheepishly. There is an English Premier League game on a big screen TV. This must be the wrong address.

“I’m sorry—I know this looks bad, but I swear I didn’t put this on,” says Smith, assigning blame for the footie faux pas to Matt, the middle of his three kids—all boys, all grown up. The youngest, Miles, in his final semester of college, was supposed to be here too, “but he’s a single guy,” Smith says. “A young, single guy that lives in Chicago. He’s trying to have a good time.” Smith apologizes again for not answering the door sooner, but he was blasting Natalie Cole’s “This Will Be” too loud to hear the doorbell.

Hold up—Lovie Smith … rocks out? “Oh, come on now,” he says, rolling his eyes. He darts into the kitchen, digs out a stereo remote and hits the play button.

Hugging and squeezing and kissing and pleasing

Together forever throughever whatever

Yeah yeah yeah yeah

You and me

The funk is casting its spell anew. Smith’s eyes are closed, his head bobbing. He’s in a groove now. He dashes through the garage—“Look at Matt leaving the garage door open,” he says, in that way fathers do—past his sky-blue ’67 Mustang and a Bears golf bag to the backyard to show off his garden, a row of gray box planters on the edge of a driveway basketball court and a putting green. One box has cantaloupe. Another has cucumbers. Most of this harvest will wind up paired with store-bought spinach and kale and crammed inside a NutriBullet for breakfast smoothies. As for those blackberries growing in clusters on the backyard fence, a bunch met their end inside a giant mason jar on the kitchen table labeled BLACKBERRY BRANDY. Smith considers his purple potion and smiles wryly. “You gotta find a way to use ’em all up,” he says.

There’s more produce in a giant bowl in the living room, an outgrowth of Smith’s farmland upbringing and a legacy of diabetes that chased his sister and mother to the grave and holds two other siblings in its grip. Make yourself at home. The early games are about to start. Matt flips from soccer (thank god) to the DirecTV game-mix channel. Chief among the eight tiles of NFL games, all playing simultaneously, is Saints-Bears.

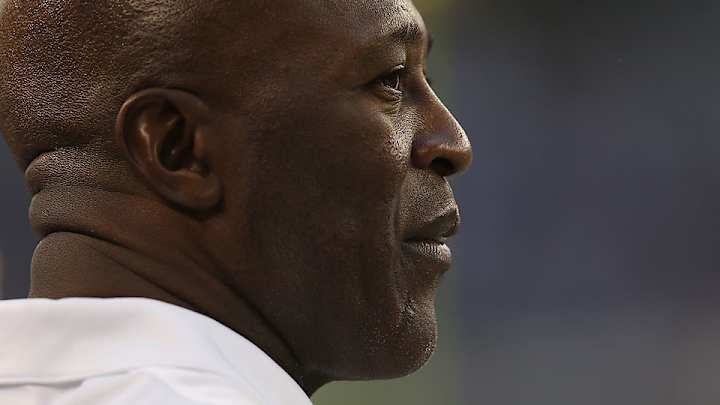

For the first time in more than three decades, Lovie Smith has the fan’s view of the game. (Andrew Lawrence/SI)

A Sunday veg-out session with a real, live NFL coach would qualify as a Make-A-Wish moment for most football fans. At best it’s a window into the logic that informs modern game plans; at worst it’s a reminder that a peripheral grasp on the game, no matter how tight, is no match for the knowledge that comes from a lifetime on the inside.

And yet it is impossible to fully enjoy this afternoon, knowing that Smith, 55, is simply too young and too good to be on this side of the TV. It’s not that the Bears weren’t within their right to terminate their relationship with him after nine years; they’re a business, not a charity. It’s that they fired him with a winning record, after a 10-6 season, one of a handful of such seasons since the expansion to 16 games that didn’t culminate in a playoff berth for the team in question. Even stranger, none of the seven other teams seeking to fill head coaching positions before the 2013 season moved to scoop up Smith, a former NFL coach of the year who won the NFC North division three times, led Chicago to two NFC championship games and came within a few Rex Grossman turnovers of stealing Super Bowl XLI.

Shortly after his dismissal, Smith interviewed with the Bills, Chargers and Eagles about their head coaching vacancies but was passed over. He wasn’t the right fit, they more or less told him. Just a few days ago he was reported to have interviewed for the vacant USC job, but he insists there’s no truth to that. He has no interest in going back to school. “I’m a Pro coach,” he says by way of a Tuesday morning text message—the capital P, his. Rather than take a step down and try to catch on with another pro staff as a defensive coordinator (the side of the ball where Smith built a reputation as a Cover 2 guru), or become a TV pundit, or lose himself down a mental rabbit hole trying to deconstruct the reasoning behind the cryptic job rejections he received, the coach disappeared. He took his 81 wins and the $5 million balance owed to him on a Bears contract that runs through the end of this season and went home. Getting here was a trip.

St. Louis, where Lovie Smith was defensive coordinator for three seasons, was the 10th step on the long climb to a head coaching position. (James A. Finley/AP)

There’s a reason why football coaches, despite their public speaking prowess and convenient campus locations, make crap career-day presenters: Their racket is nobody’s Plan A. The dream is to play. It’s only when the dream dies that coaching seems like a plausible way to make a living. Never mind that the pay is laughably low at the entry level, the hours are interminably long and the what security that is to be had is all tied to performance. The benefits—namely, the winning, the stature, and the effect you can have on people’s lives on and off the field—beat just about any spoils your standard cubicle job can offer.

Growing up in Big Sandy, a runt of a northeast Texas town serving a permanent time-out off of US 80, Smith never imagined a day when he’d see himself any differently from how he is preserved on a wall in his basement workout room: on a ballfield, skinny, shirtless and Afro-ed. (“If I only had hair like that again,” he says. “It’s been so long, I wouldn’t know what it felt like to comb hair, shampooing it and all that.”) An all-state star at Big Sandy High and All-America at Tulsa, Smith—an end-slash-linebacker-slash-safety—expected a 20-year NFL playing career for himself; this despite having spent much of his time battling through chronic hamstring problems. What he got instead was a few weeks of training camp with the Atlanta Falcons, who signed him as an undrafted free agent in the late ’70s. His tender hamstrings gave out on the first day. For Smith, the injury affirmed a latent suspicion that he never had enough rope after all to string out a run in the pros. And when Atlanta proved him right and cut him soon after his hammies healed, Smith set out upon a coaching odyssey.

The Big Sandy star and All-America at Tulsa had NFL dreams, but balky hamstrings meant his playing career never got farther than one camp with the Falcons. (L.M. Otero/AP)

That’s the other thing they don’t tell you about this racket. “When you sign up to be a coach, you sign up to be a gypsy,” says Terry (Tank) Johnson, a retired defensive tackle who played three of his seven seasons under Smith in Chicago, from 2004 through ’06. Since hanging up his cleats in 2010, he has wanted no part of a grind that demands so much moving around to move up. Johnson’s home doesn’t have a bookshelf like Smith’s, which runs the length of a basement wall and provides a handy visual timeline of his career climb. Each column is filled with helmets and game balls from his stints as a linebackers coach at Tulsa (1983-86), Wisconsin (’87), Arizona State (’88-91) and Kentucky (’92); defensive backs coach with Tennessee (’93-94) and Ohio State; linebackers again with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers (’96-2000); defensive coordinator of the St. Louis Rams (’01-03); and, finally, as head coach of the Bears from 2004 through ’12. (The souvenirs from his high school coaching stints at his alma mater and at Cascia Hall Prep in Tulsa he keeps in an office two flights up.)

The most powerful keepsakes on the bookshelf, though, are the childhood photos of Mikal, Matt and Miles. His wife, MaryAnne, sprinkled them there and throughout the house, like mile markers in a journey that never felt fully mapped out. They hark back to the growing pains along the way, like the time MaryAnne had just locked up their Lexington home and called in a panic to report that Mikal had bolted from the car a block into their drive to Knoxville, so despondent was their oldest son about having to abandon another new school after only his sophomore year. And that time early in Smith’s Chicago tenure when he would drive Miles to school in the mornings, and how his youngest whined and complained until Smith threw up his hands and transferred him to another school; there awaited another coach’s cranky kid—that of Ron Turner, the Bears newly hired offensive coordinator.

And then there was the time Smith bought Matt a new 2001 Mustang after taking the Rams job, as if to prove how serious he was about the promise he made to Matt back in Tampa, that they wouldn’t move again until he finished high school. Somewhere around 1,000 miles into the car’s life, in January 2004, Matt rear-ended another car while rushing to a basketball game. Shortly after Smith arrived on the scene, angry with himself more than anyone for buying the stupid death trap, his cell phone rang as he waited for the tow truck. It was Bears chairman Mike McCaskey, calling with the job offer of a lifetime. Smith, of course, accepted—but not at the expense of honoring a promise. Matt would stay behind with MaryAnne in St. Louis and wrap up his last two years of school, and Smith would head up I-55.

Which brings us back to this stately brick house, the 11th place the Smiths have called home in 33 years. Amazingly, throughout all the barnstorming, Smith has never had to choreograph a home move; that Herculean task always falls to MaryAnne. It was only two months ago, when Matt and his wife bought a house of their own, that Smith got his first taste. “All day I was there with the movers,” he says proudly.

His few outings to live sporting events have taught him much about the common fan’s struggle. Little things like parking, traffic and standing in line are fresh experiences.

Smith can’t remember another point in his life when he has had so much free time. For the last 30 years his days have been scheduled to the minute, a habit he picked up from his father, an Army corporal. When Smith set the schedule in Chicago, he filled it out down to the victory parade on Michigan Avenue; there but for the grasp of Grossman (who threw two picks and lost a fumble in Super Bowl XLI to doom the Bears to a 29-17 defeat to the Colts), Smith would have been the first black coach to reach the Super Bowl and win it. Instead, he shares the former distinction with his friend, mentor and former boss Tony Dungy, who faced him on the opposing sideline that rainy night in South Florida and won.

As much as Smith would have liked to be on his usual grind this season, he is relishing his downtime. His only standing obligation—self-imposed, naturally—is watching game tape three days a week, and staying on top of that is as easy as opening a laptop. Otherwise he burns through his favorite on-demand TV shows, like NBC’s “Parenthood”. He babysits Matt’s infant son, one of eight grandkids. During a nine-day visit to Costa Rica last February with his wife, Smith chased a pair of howler monkeys from their rainforest abode with a broom and machete. You know, he takes the day as it comes.

His few outings to live sporting events in between have taught him much about the common fan’s struggle. Little things like parking, traffic and standing in line are fresh experiences. When he coached, a bus dropped him off inside the stadium, a short walk from the locker room. As much as Smith misses the trappings of his former office, his appreciation for his seat on the couch is deepening. From here, he sees the game more clearly than ever.

For more than 30 years Smith has watched football with blinders on. The must-see teams were his own and the opponents next up on the schedule. The only way to watch them was from a catbird seat above the sideline or the goalposts, the enduring two-camera setup of coach’s tape. The stakes were high, so his attention level had to be too. He had to focus. He had to study. It was work.

Today? He wants to see everything. So the TV stays on the game mix for now, and the sound is kept low. This Clockwork Orange perspective isn’t recommended for regular viewers who want to know more than the score of a game and which team has the ball. It’s an array that doesn’t lend itself to individual scrutiny.

And yet Smith picks up on everything in the games: the personnel groupings, the pre-snap looks, where the ball should go and—in many instances—why it didn’t get there. When the Bears’ Alshon Jeffery catches a three-yard touchdown off of a pick play late in first half to cut the Saints’ lead to 13-7, Smith provides color commentary. “See, if you’re lined up on the line of scrimmage, there’s no such thing as an offensive pick or offensive pass interference,” he says excitedly, as Saints safety Malcolm Jenkins pleads to head linesman Tom Stabile for a flag. “You can block a guy if he’s lined up right there. So that’s what happened there. It’s not right, but it’s a pick. It’s just taking advantage of the rules a little bit.”

Watching the game mix, he picks up on everything: personnel groupings, the pre-snap looks, where the ball should go and—in many instances—why it didn’t get there.

Seeing Smith like this raises an obvious question: Why isn’t he on TV? Simple. He’s not one to criticize, certainly not publicly. Building players up is his strong suit—one that, unfortunately, doesn’t bring in ratings like tearing them down. Just because he isn’t on ESPN 10 times a day haunting Jay Cutler doesn’t mean he’s any less eager to coach again. If anything, it’s the other way around.

Besides, Cutler just made a great play. And Smith wants not just to talk about it, but to think it through. Defensive coaches like him aren’t supposed to be able to do that, or so goes one of the more common knocks against Smith. So what if it disregards two fundamental truths about coaching: 1) that there is nothing new in this game; and 2) that no coach enjoys that much success on the defensive side of the ball without a thorough understanding of what’s happening across the line of scrimmage.

Another knock against Smith: his derivative Cover 2 system—the Bear 2, which creates pressure with four down linemen, protects the deep secondary with two safeties and depends on an athletic middle linebacker to patrol the intermediate area. It has made a lot of quarterbacks look bad, from pocket passers such as Aaron Rodgers to scramblers like Michael Vick. It has also had the unintended effect of making Smith look bad, largely because his players don’t move much before the snap to force the illusion of confusion. It feeds the idea that the scheme operates on autopilot, that any good coordinator could keep the Bears D among the league leaders in takeaways, third-down efficiency and points allowed, the telltale metrics of an effective Cover 2.

Smith’s version of the Cover 2 (seen here in 2006) calls for four down linemen, two safeties deep and an athletic middle linebacker who drops to patrol the intermediate area. It’s not flashy, but it is effective. (John Iacono/SI).

Such was the logic that brought Mel Tucker to Chicago this season. The former Jaguars coordinator would keep the defense at altitude while first-year coach Marc Trestman, a CFL import, attempted to do for the Bears what no coach has done since George Halas: transform the offense into a consistently high functioning unit. Cutler and company have improved under Trestman, but the same can’t yet be said of the Tucker-led defense, which lags behind last year’s unit’s six-game numbers in takeaways (17 in ’13 versus 21 in ’12), opponents’ third-down conversion rate (42.7% versus 29.2%) and points allowed (140 versus 78). That wouldn’t look so bad if, in addition to Smith’s scheme, Tucker hadn’t also appropriated the verbiage that goes along with it. How does a team justify firing its coach while still running his defense?

Like this: The Bears D, despite the drop-off, still rates among the NFL’s most effective. And that’s after losing a perennial All-Pro middle linebacker (Brian Urlacher, to forced retirement) and the best D-line coach in the business (Rod Marinelli, to the Dallas Cowboys) along with Smith. For the coach, though, it just proves that the Cover 2 is the Bentley of defenses, that it’ll never go out of style despite arguments to the contrary. And when Green Bay starts driving on Detroit, another Cover 2 D, Smith seizes on it. “Let’s study,” Smith says. Matt puts the game on full screen.

Smith is off the couch now, an arm’s length from the screen, gesticulating as if back inside a Halas Hall meeting room. His movements are broad and purposeful. His thoughts unspool in long tangents. About the pointlessness of dropping a normally pass-rushing linebacker into coverage. (“Every time he doesn’t rush, you know what the offense is saying? Phew! Good!”) About the idiocy of pre-snap movement. (“You can’t confuse an offense. It’s basically the same thing. It’s just gap control. It’s just how you get into it.”) About the lack of appreciation for his defense’s contributions to the scoreline. (“We got punished because we took the ball away and scored. They’d say, ‘Well, you had those points, but your offense didn’t score those points.’ … It’s however you score as a football team.”)

He’s talked for a while now, and yet he’s not entirely sure he’s made his point. Perhaps seeing the game from another angle might make all this clearer. “Matt,” he says, “maybe an overhead look?”

“Dad, it’s not like that.”

“It’s not?”

“It’s not the coaches’ tape.”

Later there will be a demonstration of the proper marking technique for the Bear 2 defensive back, for which Matt will be summoned off of the couch. As the coach positions his human prop this way and that, Matt wears the expression of a son who has spent a lifetime animating his father’s ambitions. That he now works as his father’s agent seems fitting—as does Mikal’s working as a defensive assistant with the Dallas Cowboys and Miles’s intent to pursue a coaching career after graduation. “My kids all know football,” Smith says. “They really do.”

The Chicago Way: The city demands two things of its coaches: outsized personalites—from Ditka’s histrionics to Guillen’s nuttiness to Jackson’s zen cool—and distinctive facial hair. (John Biever/SI :: Al Tielemans/SI :: Manny Millan/SI)

Smith’s voice fills the room. His East Texas twang never came in so clearly, especially in the digressions about his family, where words like my (mah) and wife (wahf) really stand out; when he mentions MaryAnne expressly, he mashes her name and title into one long drawl—mahwahfMuryAnne. Smith doesn’t look or sound anything like the guy who spent nine years speaking in front of cameras and microphones in monotone delivery that made his vague and cliché-laden answers to questions about the Bears so frustrating for the local media tribe. “No head coach is gonna go through the week and start giving you [privileged] information,” Smith says. “As an organization, we decided to do this. We don’t want to give the opponent an advantage.”

And even though that tone is in harmony with the droning that emanates from podiums across the league—shoot, even the Jets’ Rex Ryan, Coach Bombast, has regressed to the mean—it never resonated in Chicago. Here, the populace demands that coaching personalities be as out front and distinctive as their facial hair. Ozzie Guillen was the White Sox’ goateed flamethrower. Phil Jackson was the Bulls’ bearded Svengali. Mike Ditka was the Bears’ mustachioed hard-ass. Smith? Not only is he hairless from the neck up, but he doesn't make foul-mouth cracks, doesn’t lead his players in pregame meditation, doesn’t throw sideline tantrums. “What I found is you look a guy in the eye and you tell him what you want, and he will fall in line,” Smith says. “You don’t have to scream and yell, especially when you know the camera’s on you, and put a guy down when he makes a mistake to get your point across.”

In the end, though, Smith’s problem was not the little he said but the frequency with which he repeated himself. His fate in Chicago was sealed by a five-word mantra: “Rex Grossman is our quarterback.” It became a catchphrase that echoed in so many failures: an offense that cracked the top 15 just once on Smith’s watch, a single playoff appearance in his last six seasons, a 2012 squad that started 7-1 but stumbled to a 3-5 finish.

His fate in Chicago was sealed by a five-word mantra: ‘Rex Grossman is our quarterback.’

This wasn’t the plan. Smith set out to build an outfit similar to the one he left in St. Louis, one where his opportunistic defense could thrive alongside a high-powered offense. But when he found himself in Chicago with more talent on defense than offense and management never was able to even the scales, he simply stitched together the best teams he could. How many other coaches would have been able to do as much with so little balance? How many others could live with being called boring in the paper each morning, to keep the locker room together? “Rex Grossman struggled tremendously our Super Bowl year, but our team never one time came close to pointing a finger at Rex or saying anything publically in the media, because we saw that our coach wasn’t concerned about it,” says Tank Johnson. “He was confident enough to say, ‘Hey, we limit [the impact of] those mistakes if we continue to play hard.’ There’s something to be said for that type of faith and that type of loyalty to your system.”

Not many other coaches keep winning in spite of their quarterback. Well, maybe one. “I did have a great example in Tony Dungy, in how he did things,” Smith says of his time as a Dungy assistant with the Bucs. “Never compromised his principles. My first year in Tampa we went 0-5 to start out the season. Each Monday, Tony said, ‘Guys, keep doing what you’re doing. Stay the course. Don’t overreact. Don’t panic. If you have a good plan, eventually you’re gonna come out on top. It’s not a straight road always. Sometimes it winds, sometimes it’s dirt. But eventually it’s going to be a paved highway.”

He harbors no ill will against the Bears, the first team to ever fire him. In fact, he says, “I loved my time here.” What he can’t reconcile, though, is why he’s still here in his living room, and not running an NFL team somewhere. He would hate to think it’s because he’s black.

In March 2006, Marvin Lewis (Bengals), Lovie Smith (Bears), Tony Dungy (Colts), Herm Edwards (Chiefs), Romeo Crennel (Browns) and Art Shell (Raiders) posed in Orlando. There are half as many black NFL head coaches this season. (Al Messerschmidt/Getty Images)

For the coach who is lucky enough to make it as far as Smith has, through the long hours, the low wages and ever-changing addresses to the top of the profession, buckle up; the air in this stratified part of the job market is even rougher. In this part of the market—call it 82 teams, the 32 NFL franchises plus the top 50 Division I schools—there are fewer jobs to go around than there are applicants who are good enough and smart enough to hold down a corner office.

Until recently, however, you would be hard-pressed to find many candidates who fit this description and were minorities—which is strange considering how many of the men inside NFL locker rooms are not white. Much of the reason why coaching staffs haven’t reflected their workforce is because minorities have been fighting for a place in the game as intellectual contributors since second-year running back Fritz Pollard, another black man from Chicago, played for and coached the Akron Pros in 1921. On and on the battle waged, a breakthrough coming when Tom Flores, a Hispanic-American, coached the Raiders to a Super Bowl title in 1980.

After Flores came the Raiders’ Art Shell in 1989, followed by the Vikings’ Dennis Green, the Buccaneers’ Dungy, the Eagles’ Ray Rhodes, and the Jets’ Herm Edwards. It was hardly a tidal wave. In 2002, a report presented by attorneys Johnnie Cochran and Cyrus Mehri called “Black Coaches in the National Football League: Superior Performance, Inferior Opportunities” analyzed every league season from 1986 through 2001 and found that black coaches—mostly that fab five—averaged 1.1 more wins per season and reached the playoffs more frequently than their white counterparts (67% versus 39%). Affirmative action, the report implied, was good for business.

In December 2002, NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue, acting on the advice of a committee of owners led by the Steelers’ Dan Rooney, adopted the Rooney Rule; it requires, among other things, that teams interview at least one minority candidate for open head coaching positions. The impact was immediate; the number of minority head coaches jumped from three in 2003 to seven in 2006 to an all-time high of 11 midway through the 2011 season. And then on the Monday following the end of the 2012 regular season, seven coaches were fired; 10 days later the Jaguars fired Mike Mularkey. Of the eight coaches on the street, two—Smith and Kansas City’s Romeo Crennel—were minorities. No minorities were hired as head coaches.

And yet if all you had to judge the league’s diversity standard by was last month’s clash between the Steelers and Vikings in the annual London Game, you wouldn’t think there was a problem—especially if you were English and an NFL novice. All you’d see was a sight foreign to Wembley Stadium and to soccer in general: two black men, Mike Tomlin and Leslie Frazier, on the pitch calling the shots. You’d think this is how all footie must look like back in the States. “The other side of that,” says Smith, “is that there’s only one other coach [the Bengals’ Marvin Lewis] back home.”

The sociologist Harry Edwards might think that sad if he hadn’t seen such a scenario coming almost 30 years ago, when he teamed with the 49ers’ Bill Walsh to build a diversity coaching initiative in San Francisco that would become a template for the league. “The fundamental problem was that creating a pool of viable candidates who the owners, GMs, head coaches and others knew about and at some point might be willing to bring on really was a franchise-by-franchise [decision],” says Edwards, who remains a 49ers advisor. “None of it is organically related to how football coaches typically emerge within the NFL system.”

Pupil and mentor: Lovie Smith and Tony Dungy shared a moment after Super Bowl XLI, when they jointly broke the color barrier for head coaches at the Super Bowl. (David Duprey/AP)

The fundamental problem is that many of those candidates emerge from the college ranks, where minorities coaches have historically had an even harder time than in NFL. At the time the Rooney Rule was adopted, Division I schools had hired a grand total of 21 black coaches ever. But thanks to the influence of the Rooney Rule and the efforts of organizations like the Black Coaches Association, there are about as many minorities coaching at schools now.

In Chicago, Smith used the junior assistant positions on his staff to get minorities in the door; he treated them like graduate assistants on a college team.

To flush the stagnation in the pool, the league has discussed expanding the Rooney Rule to include minority candidates for vacant coordinator jobs. Robert Boland, a coach agent turned sports management professor at NYU, suggests a better idea: use the Rooney Rule to bring more minorities into the ground floor of NFL teams and let them work their way up.

Lovie Smith was already doing that. While in Chicago he used the junior assistant positions on his staff exclusively to get minorities in the door; he treated them like graduate assistants on a college team. “I’d say, ‘Guys, I’m gonna bring you in here for a couple years, and then after that you need to get another job,’ ” says Smith. “I wanted them to go out there and do their own thing and then bring them back later on.” His alums include Andrew Hayes-Stoker, the running backs coach at Florida International; Harold Goodwin, the Arizona Cardinals’ offensive coordinator; and his son Mikal, a defensive assistant with the Cowboys.

“Now that I think about it,” Smith says, “are they playing yet?”

No, Denver-Dallas is still a few minutes away. And when it does finally arrive, and Mikal flashes on the screen, it will take Smith a beat to recognize his own reflection. The nice thing now is that a black assistant on an NFL sideline is now ordinary enough to miss entirely.

But before that moment arrives, Matt receives an alert on his phone.

“Miami of Ohio just fired their coach, Don Treadwell,” he says.

“Huh?” says dad.

“Miami of Ohio fired their coach.”

“They did?”

They did. Just like that, another brother—gone. The mood at the house is sub-basement-level now. The only sound comes from the TV. After a long pause, the name of Mike Haywood, Treadwell’s predecessor at Miami, comes up. Three years ago Pittsburgh hired Haywood away from Ohio; he was to be the school’s first black coach in a major men’s sport. But before he ever devised a game plan, Haywood was arrested on felony domestic violence charges, which were ultimately dismissed. Too late. The Panthers fired him.

“What is he doing now?” Smith asks.

He started a couple energy firms in the Houston area.

“He’s out of coaching,” Smith says.

He’s waiting on another chance. Just like Smith. “I cannot wait for this next opportunity,” he says. “Chicago was just a learning experience. I’m so much more of a good football coach now than I was back then.”

Hopefully, it’s not a long wait. The window of opportunity can shut quickly on the minority coach, after all. It operates the same for winners like Jim Caldwell, who nearly went undefeated in his rookie season leading the Colts in 2009 and helped spark the Ravens’ Super Bowl run last year when he was promoted from quarterbacks coach to offensive coordinator in December; and for losers like Jon Embree, who after a 4-21 college tenure at Colorado took a job as the Browns’ tight ends coach and is making a Pro Bowl player out of Jordan Cameron. The market doesn’t recycle them as readily as it does men like Norv Turner and Wade Phillips. The hot trend is always morphing—from professorial (Dick Jauron, Marc Trestman) to college cult figure (Steve Spurrier, Chip Kelly) to young and brash (Eric Mangini, Josh McDaniels) to coach’s kid (Lane Kiffin, Rex Ryan).

We are family: Lovie with Mikal, Matthew, MaryAnne and Miles after the NFC title game win. (Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images)

A minority coach, it seems, can’t be any of these things. He never seems to fit. He is always a minority first. And for Smith, that’s hard. Race is such a central element of his story—from being bused to segregated schools as a kid, to standing at the head of a mixed-race family (MaryAnne is white), to breaking through to the Super Bowl with Dungy—and yet not very central to his life. His mother made sure of that. “That was never a part of our makeup, that [race] was going to stop you,” he says. “The only thing that’s gonna stop you is what you do on the field, who you are, all of that. That’s why I just can’t think that race is…

The window of opportunity can shut quickly for a minority coach. The market doesn't recycle them as readily as it does men like Norv Turner and Wade Phillips.

“That’s why it’s so important to keep going. You just can’t accept that as a reason, because in the end if you work hard and you do things the right way and you’re good at what you do, things are gonna work out for you. And that’s the only way I can see any of this. I just refuse to believe that people [are racially motivated].”

So rather than waste the rest of this fading Sunday rehashing every token interview he’s had in his career, why not dig into this Broncos-Cowboys game everyone’s so excited about, finally on the TV in full? Why not give the X’s and O’s lecture a break and just let all this passing offense wash over? Or take a stab at guessing the score at the end of each quarter? Or the number of yards Peyton Manning and Tony Romo will have at the end of the game? Why not take a moment to meet Mary Jane, the family’s overfed cat, as she curls up in the crook of Smith’s arm?

Because soon, the sun will be gone, all the guesses will be wrong and Tony Romo—at the 506-yard mark; who had that?—will throw an epic interception that will have Smith whooping, rocking back and startling the cat damn near out of her fur. That’s when you’ll see Lovie Smith for who he truly is: a man who loves football way more than he lets on. Just wait ’til he gets back in the game. He’ll show you.

The man is always on watch. (Andrew Lawrence/SI)

Andrew Lawrence is an SI staff writer, specializing in motor sports for the website and magazine. Follow him on twitter @by_drew.