The Other Side of Brady

FOXBOROUGH, Mass.—Anyone who profiles Tom Brady has to confront certain images of him: the supermodel wife, the GQ covers, the designer clothes, the movie cameos, that kind of thing. That’s Tom Brady, the part that’s not relatable.

Then there’s the story arc, also familiar: The kid who grew up in California, who went to Michigan and didn’t start, who met with a sports psychologist, who did start (eventually) for Michigan but fell to the sixth round in the NFL draft, who took over as the Patriots’ quarterback in 2001 when Drew Bledsoe suffered a hit so severe it caused internal bleeding. That’s also Tom Brady, the part that’s more relatable.

That’s the baseline for a Brady story, for any Brady story—Brady the star, compared to Brady the regular person. But the more I looked into why Tom Brady is playing this well at age 37, why he’s at least in the conversation for league MVP, the less he seemed like either of those worn narratives and the more he seemed like, well, not at all what anyone expected.

For a story that ran in this week’s Sports Illustrated magazine and is available on SI.com, we looked at Brady’s routines. He has a lot of them. His schedule is mapped three years in advance. His workouts are geared for short- and long-term. They take place on sand, on land and in water. His diet is based in part on what season it is and what kind of foods —hot property, or cold property—will help him maintain “internal harmony.” Yes, internal harmony was something that he talked about.

Tom Brady Wants To Play u2018Foreveru2019

He is 37 and in his 15th season, and there’s no end in sight. Greg Bishop uncovered the unorthodox regimen, every aspect of which is micromanaged and mapped out years in advance, that the Pats QB follows to prolong his Hall of Fame career. FULL STORY

It’s less a training method for Brady than a life philosophy, which he hopes to teach to other athletes and other people once he’s done with football. He arrived at that philosophy through Alex Guerrero, a 49-year-old California native with a Master’s degree in traditional Chinese medicine. Brady calls Guerrero his “body coach.”

He also has a throwing coach in Tom House, who replaced the late Tom Martinez in that capacity, and performed three-dimensional analysis of Brady’s throwing motion. And a trainer in Gunnar Peterson, who works with celebrities such as Bruce Willis and Sylvester Stallone and Jennifer Lopez. Peterson said three athletes stand out in his decades of training: Pete Sampras, the tennis great; Kevin Love, the basketball star; and Brady.

Brady tells teammates he’s going to “play forever,” and he’s only partly joking. This support system is designed to allow him to maintain his current skill level well into his 40s. (Guerrero floated age 48, even, as how long Brady could play for.) It’s not something he does part of the year. It’s something he does every day.

“I’ve always been intrigued by different methods,” Brady told me. “I enjoy learning. So when I came to meet Alex through Willie McGinest, Alex’s thoughts made so much sense. It’s a very common-sense approach. I don’t see it at all as a sacrifice. I’m going to do something one way or another to enhance my performance. I may as well do the right things.

“That’s really what I’d love to ultimately share with the next generation of athletes. You see all these stories of guys with concussion issues or knee replacements or hip replacements. It doesn’t need to be that way. You have to train right. More so than anything else, I feel like this is what my kids need to be learning.

“I was told by my doctor after the ACL tear that my knee would never be the same. That I would never be able to run around and play with my kids, which was all a bunch of bulls---. That knee feels as good as my other knee. It never swelled up one day in the last six years. I would say that’s through everything we’ve done, with nutrition and exercise, body work, never letting little things become big things.” This was an unexpected side to Brady, but one that makes perfect sense. Other than the season he lost to the ACL tear, Brady hasn’t missed any significant time since he took over for Bledsoe in 2001.

* * *

The Other Side of Brady

Photo: Winslow Townson for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Winslow Townson for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Winslow Townson for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Jeff Haynes for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Winslow Townson for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Photo: Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

I talked to nearly two dozen teammates, former teammates, coaches, former coaches and executives about Brady. There were a million stories—glimpses into his leadership, his competitiveness, his persona away from the spotlight. Together they provide some insight into an icon who jealously guards his image beyond what we see on the football field.

To Robert Kraft, the Patriots’ owner, Brady is like a “fifth son.” Kraft relayed the familiar story of the first time the two met. It was right before Brady’s second season. “He came down in training camp and introduced himself,” Kraft said. “Here was this skinny beanpole, with this pizza under his arm. He says, ‘I’m Tom Brady.’ ”

Brady and Robert Kraft after the Super Bowl XXXIII win. (Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated)

“I know who you are,” Kraft told him. “You’re our sixth-round pick.”

“I’m the best decision this organization has ever made,” Brady responded.

“Normally, that kind of bravado would be a turn-off,” Kraft said. “I don’t know how to explain it, but with him it resonated.”

To Bill O’Brien, a Patriots assistant from 2007 to ’11 and now the Texans coach, Brady could seem obsessive in his desire to win anything. “He viewed practice like a game,” said O’Brien. “He was competitive in walk-throughs. I remember we used to do a bucket toss on Fridays, in the end zone, to work on the fade ball. It was always a competition between him and Brian Hoyer or him and Matt Cassel or Ryan Mallett. If he didn’t win that day, he was not happy. You couldn’t talk to him for a bit.”

Brady talks with Bill O'Brien, then the Pats’ quarterbacks coach, in 2009. (Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated)

To Brian Hoyer, a 2009-11 New England backup who’s now with Cleveland, Brady was a blueprint. He remembered when Brady broke a finger during practice and Guerrero spent what seemed like the next 24 hours attached to Brady’s hand, even massaging it in meetings. “It was eye-opening to see how committed this guy was,” Hoyer said. The broken finger “was just another challenge to overcome.”

When Hoyer became a starter in Cleveland in 2013, he tore his ACL, and he called both Guerrero and Brady regularly for advice. (Another Brady tidbit: He is known to respond quickly to email.) Hoyer did his rehabilitation with their influence. He found an anti-gravity treadmill in the Cleveland area—not as easy as it sounds—because that’s what Brady used. He came back from the injury to hold off Johnny Manziel for the Browns’ starting job this season. “I always hear him, still,” Hoyer said. “He never wanted to come out, even during run plays in practice. He would always tell me, ‘Be ready for your opportunity,’ but then he would take all the reps. Except when there was a new center. Then he’d be like, ‘Hoyer, you got this one.’ I took those words to heart when I got the opportunity and had the injury and Johnny was drafted here.”

Brady celebrates with Brian Hoyer after a Hoyer touchdown pass in the 2010 regular-season finale. (Jim Davis/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

“By the way,” Hoyer said, “I still can’t believe he’s on Facebook. I remember when Twitter first came out. He would be like, ‘How does it work?’ We’d give him s--- for being the old guy.”

To former NFL tight end Cam Cleeland, who played for the Patriots in 2002, Brady was a glimpse of greatness. Cleeland still remembers the touchdown pass he caught from Brady. How could he forget? It was a Monday night game, at the Meadowlands, against the Jets. It was pouring rain as Brady dialed up “Fake 16 All Cross,” calling for Cleeland to run across the field toward the back corner of the end zone. He ran the route, and Brady delivered a touchdown strike. Somehow Cleeland’s spike made it onto one of his trading cards, and he kept whole packs of them to remind himself of the touchdown he caught from Brady, one of 13 over his career. “His leadership,” Cleeland says, “is something that needs to be studied.”

Cam Cleeland caught a glimpse of Brady’s greatness—and this TD pass against the Jets—during a season with the Patriots in 2002. (Bill Kostroun/Getty Images)

To former wideout Troy Brown, the Patriots’ second all-time leading receiver, Brady is simply the best. Brown, who has done a few hundred interviews about Brady over the years, said that the most common topic is always Brady’s off-field persona. “You don’t really see him like Peyton Manning, all up in all those commercials,” Brown said. “You don’t see him out. He’s always giving the politically correct answer. So people always want to know what he’s really like. Does he have a sense of humor? I tell them, ‘What you see right there, that’s Tom. He’s a regular dude.’ ”

Troy Brown and Brady at the Pro Bowl in 2002. (Charles Rex Arbogast/AP)

“He could be doing a million ads, but that’s not him. Maybe that’s why people seem to like Peyton Manning more than they like Tom Brady. I always tell Tom he’s funny, he can be a comedian, he should do more commercials. I’m sure he would be more popular if he did.”

As one of Brady’s teammates during the run when they won three Super Bowls in four seasons, Brown said he gets a little tired of hearing about Brady’s lack of a supporting cast. So this is how he looks at it: “If all Tom Brady played with is nobodies or guys without talent, if all he has is guys who can’t play, he has to be the best who ever did it. Or if we aren’t all that bad, then I guess you could have an argument.”

To Christian Fauria, a Pats tight end from 2002 to ’05, Brady’s routines were “almost like being in prison.” They were that regular, that clockwork. “Is he slower than he was? Yes,” Fauria said. “Is he weaker than he was? He was never really that strong. Is his arm-strength diminished? Sure. He’s 37. But people make way too much of that. He’s not getting hit a lot. He has a great routine. He’s religious about it.”

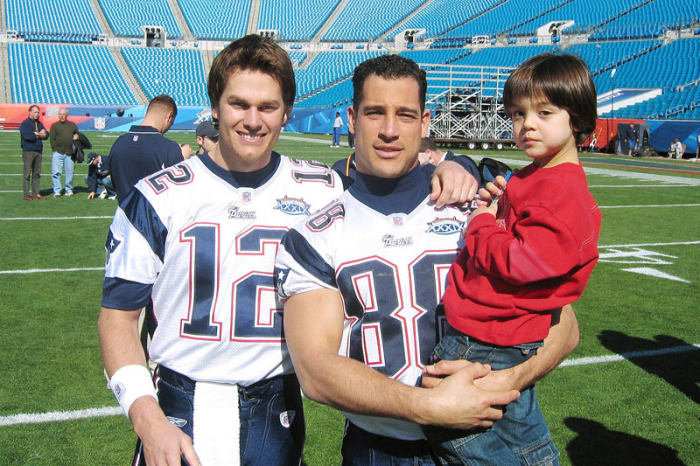

Brady with Christian Fauria and Fauria’s son, Caleb, at Super Bowl XXXIX. (Sports Illustrated/Courtesy Christian Fauria)

And intensely competitive no matter the setting. Fauria recalls a charity basketball game a few years back: “Brady rolls up with this Dan Cortez headband on. He’s serious. Now, this is for charity. We’re playing against cops and firemen. But they don’t know Tom at all. I remember he took a timeout. He’s like, ‘Come on, guys!’ Next thing you know, he’s banking in three-pointers! He’s driving the lane! I think he might have got a concussion that day. But that’s Tom.”

Fullback Heath Evans saw that side of Brady often when he played for the Patriots for four seasons in the 2000s. “I remember the verbal battles he had on the field,” Evans said. “Like with Ray Lewis. Tom would say the craziest stuff. I can’t repeat it all. But it was respectful, respectful trash-talking. Tom wouldn’t do that with everybody. He’s not going to waste his time with any weasel. Only the elites.”

Brady and Heath Evans in training camp in 2006. (Steven Savoia/AP)

But that’s not the side of Brady the public sees. “Take away the cute face and the designer clothes and listen to his post-game pressers, and it’s Bill Belichick speaking,” Evans said.

“The young kids need to listen up and take notes,” Evans said. “You can say a lot and say nothing. The stiff-arm Brady gives to the media, especially away from the field—that only makes him more attractive to people. That makes him more special. He’s not everywhere. He’s not posting on Twitter all the time. He leaves a little intrigue. This younger generation, they’re focused on all the wrong things. They have the right examples right in front of them. But it’s all about their brand. Look, the best thing for your brand is to have the respect of your teammates, the respect of your coach, and win.”

Photo by Winslow Townson for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]