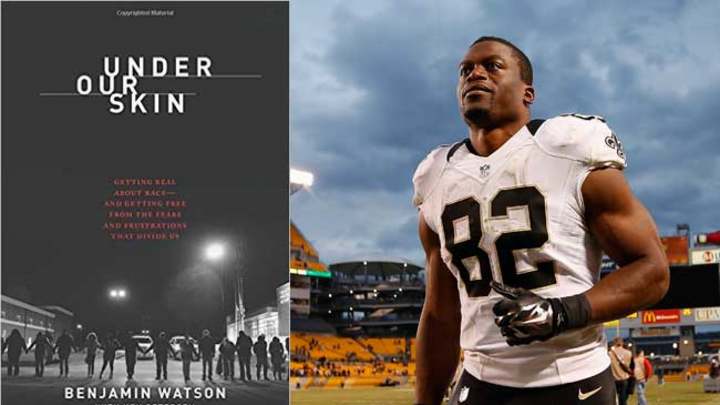

Benjamin Watson Goes Deep

NEW YORK — In his 12 seasons in the NFL, Benjamin Watson never dreamed that he’d be spending his bye week talking about a book he wrote. But there he was this week in midtown Manhattan, accompanied by his wife, Kirsten, and their 3-month-old daughter—the youngest of their five children—to start his book tour for Under Our Skin.

It all started last summer, when the Saints tight end saw news reports about an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown, being fatally shot by a white police officer, Darren Wilson, in Ferguson, Mo., and the ensuing riots. Three months later, while Watson was playing the Ravens on Monday Night Football, the news broke that a Missouri state grand jury did not indict Wilson. (The Justice Department would also eventually clear Wilson of federal civil rights violations, with attorney general Eric Holder saying “the facts do not support the filing of criminal charges.”)

A few days after the grand jury announcement, his feelings still raw, Watson authored a Facebook post that went viral. It was just a few hundred words about the complicated emotions he felt upon hearing the news that night: anger about past and present injustices, embarrassment over the violent protests, sadness for the loss of life, sympathy for both Brown and Wilson without knowing all the facts of the night, and both hopelessness and hopefulness about the racial divide in America. His book grew out of that dispatch and explores the many nuances of the Ferguson case and similar ones from around the country.

On the field, Watson is having a career season at age 34, but he’s trying to make an even bigger impact off it. In his book, he weaves his personal experiences as a black man with the events of the past year and asks readers to confront how and why race divides America.

VRENTAS: From a Facebook post to author of a book. How did it happen?

WATSON: I never thought, a year ago, that I’d be sitting here talking about a book I had written. The incident in Ferguson happened during training camp last year, and I was following it like everyone else, and waiting for the [grand jury] decision to be made. It came down during our Monday Night Football game, and I remember coming home and watching CNN, FOX and the local news, seeing those images and feeling all those emotions I ended up writing down. I didn’t quite know what to say or how to say it, but I’ve always kind of liked to write a little bit. Over the course of those next two days, I started to write down those thoughts on my iPhone. I didn’t even know how to post to Facebook at the time, so I sent it to somebody and they put it on my page. My wife said, “Did you post something to Facebook? My feed is going crazy.” My phone had died, and I had no idea. Over the course of the next few months, I had the opportunity to speak at some churches, social events, and go on TV to talk about my thoughts. That led to people saying, “You should expand on that,” and the opportunity was presented to write this book.

VRENTAS: How much of a challenge was this book, not just in finding the time to do it, but also in tackling such a complicated subject?

WATSON: Fortunately for me, I worked with a great writer in Ken Petersen. He helped me a lot, pulling things out of me and helping me to unpack a lot of these ideas. You have this short Facebook post, but how do you turn that into a book? What are the underlying stories of your life that brought you to this point to have those certain emotions, and to be able to sit there and dissect them all and see things from different angles? During the wintertime, I’d be on an airplane, and I would just start writing—my ideas, more and more thoughts about each emotion. The meat of the writing came between June and July when we really decided, OK, we are going to do this book thing. My wife got me a new computer, and got me a desk. There were some late nights there, but I had to get most of it done before training camp, because we wanted to get it out around the year anniversary of Ferguson. Even during training camp, there were some late nights when I would get back from practice and be on the phone with Ken, talking about chapters, reviewing things and writing a little bit on my own late at night. It was a hectic process but I’m really happy with the turnaround. That was my first experience with anything like this, so I had no idea that books take a year, two years. I didn’t know. To have it turned around in a rush like that in a few months is something that rarely happens. But I think this topic is something that is very important, and very pertinent to where we are—something that doesn’t seem to go away. So I think the timing was right.

VRENTAS: You write in the book’s introduction that your father said he had not seen protests like this and a movement addressing race relations in cities across America since the upheaval of the 1960s. What change do you hope can come out of this period of time?

WATSON: He said that a little while ago, and it was really weird because in our lifetime, we have never seen these types of frequent protests that are happening all the time. Number 1: it makes us realize that we don’t have it all together. We have done a great job of coating over things, and we are very cordial a lot of times. Sometimes we are not, but we have the ability to be cordial with each other, to go to schools together, and to vote, and to be integrated. We have black friends; we have white friends. But it shows that when it comes to these divisive incidents, we all come into it with a certain lens and certain assumptions based on our heritage, our background. We still have these issues. The ‘60s, and the time period before that, were nothing compared to now. We have come so far. It’s not saying that we are in the same place, because that would be a lie. But we do, however, have a lot we need to deal with and a lot we need to be honest about. Hopefully from this period, we get to a point where we can have honest conversations and ask questions and confess and forgive and repent from some of the attitudes we have. Whereas our actions may be inclusive, some of our attitudes may not be.

VRENTAS: Was that your goal in writing the book, to spark an honest a conversation about the deep-rooted issues surrounding race in our country?

WATSON: Yeah, because you’ve got to put stuff on the table. That’s one thing I’ve learned as an athlete. We have a saying: The eye in the sky don’t lie. Every day, we come in for practice, and we turn on the film on the projector. Did you block the guy? Yes or no. You can’t lie about it. You can come off the field and say to the coach, I didn’t hold him, and then you turn on the film and you’re holding. There is no need to lie about it. Part of it is putting stuff out in the open, and not being afraid that somebody is going to be offended by our ignorance or by something that ticks us off because of what we have experienced from somebody who doesn’t look like us. Also, part of the book is debunking the whole idea of race. A struggle with the book was using the term race, because the term race in and of itself creates, in my opinion, racism. It is such a loaded term that really, biologically, genetically doesn’t have much to stand on. We use the word because that’s how we understand things in this country, but when we put that word out there it is so charged. Automatically, it makes us put people into certain boxes, and from that we’re able to say, he’s better and she’s worse.

VRENTAS: You also write in the book about going to a recent doctor’s appointment where you had to check a box to indicate your race. Instead of choosing “African-American,” you marked “Other,” and filled in, HUMAN.

WATSON: I would have just checked that box, but I was in the middle of this whole epiphany and writing this book, and see, this is what I’m talking about. You’ve got “African-American.” What does that even mean? I’m not African. I’m from Norfolk, Va. You’ve got “White,” this, that, and the other, and then depending on what decade it is, it changes. All of these categories, what do they even mean? I think that’s part of the growth we have to have.

VRENTAS: Earlier this month, we saw the University of Missouri football team play a role in spotlighting a protest about treatment of minorities on their campus—two hours west of Ferguson—by going on strike. How do you view what happened at Mizzou, and using sports as a platform for social issues?

WATSON: I enjoyed seeing the unity that happened on the football team, with the coach, the white players, the black players, all of them taking a stand and saying, “Hey one of our brothers is hurt, and this is defending one of our brothers. I may not understand it 100 percent, but because I love him, I can empathize with him and stand in solidarity.” That’s something we would do well to learn from. The great thing I saw was that picture of everybody on the team standing together. As an athlete, I’ve been asked that question before about using your platform, and for me it’s not necessarily about intending to use my platform. It’s about caring and speaking when I feel led to; it’s about being abreast of things that are going on; it’s about understanding that I am a citizen of this country and I care about what happens to this country. I pay taxes, I vote, so I feel like I should be able to talk just like anybody else. A lot of times, we think that athletes should be over here and everything else outside of athletics you should leave alone: religion, politics, whatever it is. But we don’t do that with in any other profession. We allow lawyers to be involved, politicians, mailmen, whatever your occupation is. Athletes are simply people who have been blessed with a tremendous gift to play sports, but we still care what is going on around us.

VRENTAS: What kind of reaction have you received among your teammates from your Facebook post, and now your book?

WATSON: Some of my teammates said, “My grandmom saw your Facebook post,” or “my mom told me I need to come talk to that Ben guy.” It was crazy because most of my teammates, black and white, and my coaches, said, “That’s how I was feeling about this, but I didn’t know how to say it. You gave words to how I was feeling.” That was mainly the response I got, not just inside the locker room but also outside of it. I think we all have these emotions sometimes, but we’re scared to say it. And I’m scared, too, sometimes. You never know what kind of pushback you are going to get, but the response from my teammates just sparked conversation. I have a story in the book about one particular teammate of mine. We were talking during a training camp practice, and his sister had just had a daughter with a black man, and he was telling me he was looking at a lot of these things differently now, because he knows they are going to affect his niece. How is she going to look at the Rachel Dolezal situation? How is she going to feel about Ferguson? After practice, that night I called Ken, and I was like, I’ve got a story, and I’ve got to write about it. There’s a respect there, and because of our different experiences, there are some things we just don’t understand about each other. The cool thing about sports is that you are in a relationship with these guys, we are with each other all the time, and we know that we are disagreeing and agreeing in love. We can disagree and still go out and play together, and go try to kick somebody’s butt together. But at the same time, we can intentionally try to learn from each other.

VRENTAS: Are you proud to be opening these conversations on your team?

WATSON: Yeah, because it is something that is really needed. The guys got copies of the book, and everybody has been asking forever, “When are we going to get a book?” It’s been pretty fun, and honestly pretty humbling. I can’t express what it means to have a book. I still can’t believe it. It’s humbling for your teammates to appreciate what you’ve done and read it.

VRENTAS: You write in one section of the book about black players being subjected to being called the n-word, from fans or on social media. How common is that today?

WATSON: I mentioned in the book the former quarterback at Michigan, Devin Gardner, because he said he experienced it a lot. Fortunately for me, that’s not something I’ve experienced a lot. But reading things he said, and also other players I know who have experienced that, it’s sad. It’s something that as an athlete—a black athlete—you sit there and hypothesize what is going through people’s heads when you excel and when you don’t. Because you automatically think it is going to go down that road if you are doing poorly. That when you are doing well, you are cool, we like you, sign an autograph, kiss my baby. But if you are making the team lose, or they are upset at you, it is going to go to race, because that is kind of the lowest insult that can be thrown at somebody. It is kind of this weird balance: You play, and you live with and operate with the understanding that can happen.

VRENTAS: Black quarterbacks seem to experience that more than any other position.

WATSON: They definitely do. I was talking to my father; he played at the University of Maryland in the ’70s. It wasn’t very long ago when there were a couple positions you couldn’t play if you were black. You couldn’t play quarterback. You couldn’t play middle linebacker. You couldn’t play center. Positions that have responsibility, decision-making, intellectual positions where you are directing other men. Some of that definitely still prevails. You can see it in the comments. You can see it even in how black players, black quarterbacks are talked about as far as their athletic ability or their intellect. Things like that that you pick up on. We’re definitely at a place where we have black quarterbacks, we have black middle linebackers, we have all those things, but I know you see it firsthand that there is still this default that goes to, if he’s not doing this, it’s because of this. He’s black, and he shouldn’t be out there.

VRENTAS: What position did your dad play?

WATSON: He played linebacker. Not middle linebacker, outside linebacker. I wish I would have played quarterback. I really do. I try to tell my kids, if they’re playing football, they’re playing quarterback. Backup quarterback, so they don’t get hit. I could never throw very well, and I always wanted to be a wide receiver because I loved Jerry Rice. But if I could do it over again, I’d have played linebacker or defensive end, so I could hit people and not get hit. But that ship has passed.

VRENTAS: Your career has turned out OK. Speaking of which, you’re having a career season at age 34. How?

WATSON: She cooks my meals. (He points at his wife, Kirsten). I’m fortunate to be able to still play. My first five years were rough. I had a lot of surgeries, a lot of injuries. I didn’t think I’d make it past five years. But my last six years, health-wise, have been a lot better. I’ve been fortunate I haven’t had any major surgeries the last six years and started to really learn about how to take care of my body. It’s amazing when you spend the time and put the effort in. It’s what you eat, it’s your rest, soft-tissue work. I learned a lot along the way that I didn’t know early in my career.

VRENTAS: When the team traded away Jimmy Graham in the offseason, did you know the Saints were counting on you to be the guy at tight end?

WATSON: I didn’t know anything, honestly. I was very surprised that they traded Jimmy. He got the big contract the year before, and he was our offense, basically. Drew [Brees] and Jimmy set all types of records. And other than that, he was a good friend. We still talk all the time. I really hated to see him go, and I hated to see him go that way. But you always understand that football is a business and the Saints saw it as an opportunity to make the team better. My approach didn’t change. My approach has always been to be prepared, to know what to do, have my body in shape to make plays in the blocking game or the passing game. I didn’t change my routine or get excited or anything like that. I’ve been playing this game for a long time, and I understand that when you least expect it, it is going to be your turn. That’s just how it goes.

VRENTAS: You’ve made the most of your opportunity, even though the team has been very up and down this season.

WATSON: Which is miserable. I really wanted to come here and talk to you after a win. Or maybe after a loss that wasn’t so lopsided. But to go home, to Virginia, and get beat like that [against Washington] was rough. I almost didn’t come on this trip [laughs]. It hurts. You put a lot into it. The goal is always to win. You want to contribute, you want to catch balls, you want to make plays, you want to be an integral part of the offense. But ultimately you are there to win football games. Defensively, we’ve struggled in some games. Offensively, early in the year, we struggled in some games. We haven’t put it all together many times. When we have put it all together, we have done well and we have won. Football is a very complicated game, but at the end it comes down to blocking, tackling, throwing and catching, picking up blitzes, and protecting our quarterback. We have one of the best in the game, and when we protect him, he can make plays for us. It’s been frustrating on everybody, though, especially our fans.

VRENTAS: You were drafted in the first round by the Patriots in 2004, and your rookie year, the team won a Super Bowl. How did that experience shape your outlook over the rest of your career?

WATSON: That year was rough for me because I tore my ACL. You win a Super Bowl as a rookie, but I felt like I didn’t really win a Super Bowl because I wasn’t able to take the field. I have the ring, but it doesn’t have the same feeling. The Super Bowl I was out there playing in, we got beat by the Giants. So I still want that elusive Super Bowl when I am out there making plays and winning the Super Bowl. That’s what everyone is chasing. But I’ll tell you what it did do, being in New England all those years taught me how to win, and the recipe for winning. I also didn’t realize that a lot of the league wasn’t winning. Because you get so used to it there, to going in, doing things a certain way and winning. And then you leave and realize, Wow, a lot of guys don’t have the opportunity to win. I had a lot of hard times there, I had a lot of injuries, and it was up and down for me. We haven’t won as much the last six years, but there are a lot of things I have enjoyed about being in Cleveland and New Orleans.

VRENTAS: So, what is the recipe for winning?

WATSON: Bill [Belichick] has a little magic ball back there, and he just knows what everybody is going to do. [laughs] I don’t know. They obviously have an elite quarterback. And they do a great job as coaches of putting guys in a position for them to be successful according to their talent. They will have certain guys, Julian Edelman, or Kevin Faulk when I was there, who all he did was third down because that was his thing. Everybody had his niche. On third down I rush the passer, or I’m the third-down back, or I’ve got to block these five plays. And there is such an expectation there of winning that when you don’t, it is miserable, so guys try to win at all costs. The expectation level is ridiculous, it is so high, but that’s why they’ve put together such a great string of victories. It’s the culture there.

VRENTAS: Earlier this week, the Saints let defensive coordinator Rob Ryan go. Different side of the ball, but he’s a coach you’ve been close with for a while right?

WATSON: Rob, that’s my guy. When I came out in 2004, he was in Oakland. You know when you are in college, and the NFL coaches come on campus and visit? He was like that scary guy with the long hair. Hey, you guys see that big dude? Rob Ryan, he’s from Oakland. Scary dude. I texted him after he got let go, and told him, “You were the scary guy in ’04, and now you are my friend.” I was with him in Cleveland in 2010, and we had a really good defense that year. Then he went to New Orleans when I got there in ’13. It was tough to see him fired. And the guys love him. Every guy I know who has played for him defensively likes him as a coach. We’d stand on the sidelines during a special teams period, and me and Rob will talk about whatever: real estate, Cleveland, some guy in the past that he coached that he really liked, or he’ll say I killed his defense on a shake route in practice. When I was with Cleveland and he was in Dallas, I had a really good game against the Cowboys, and he’d still talk about it, saying, “Yeah man, you got my defense.” But from his own mouth, he understands that it’s a winning business, and this can happen when the numbers aren’t there. I’m sure he’s going to be working somewhere else.

VRENTAS: Now that you’ve written a book, what’s next? Will you continue down this path after your playing career is over?

WATSON: I don’t know what’s going to be next, to be honest with you. I know the football career is coming down to an end, and I know there are some opportunities whether it is broadcasting or books or ministry. We’re just kind of open. We don’t even own a house, we rent, because we don’t know where we are going next. I do think it was instilled in me very young to be involved, to listen, to think, to express myself, to care for people, all those things, so no matter what I am doing, I think I will always want to have a voice when it comes to injustice, and challenging us all to do better, and trying to unite people.

VRENTAS: This is the last year of your contract with the Saints. Do you want to keep playing after this season?

WATSON: Some days I do. Most days I don’t. But it’s week to week. I think that I have had a good career. I have played 12 years. My goal is to be healthy at the end of the year, and we’ll see what’s next. This is the last year of the contract, and I’ll be 35 in a month.

VRENTAS: On social media, you asked others to tell you who they are under their skin. Who are you under your skin?

WATSON: Under my skin, I’m a Christian, I’m a father, I’m a husband. That’s it. That’s who I am. Sometimes, we can think that our skin, our facial features or our physical talents are what we are. In football, that can really be the case. That’s something that I struggled with earlier in my career, tying my identity with my occupation. If I had a great game, I was happy-go-lucky. If I had a poor game, I didn’t want to talk to my wife, and I was being a jerk to everybody. There’s nothing wrong with being disappointed, but there is a difference between saying that your worth is all tied up in how well you perform in your job. That’s not the case. My talent is to write things and to play football, and that’s all important. But when we understand our worth, we also understand that other people have worth not just based on their talents as well. That’s another important lesson that I hope people have grasped from the book.