Before Chris Borland, There Was Jacob Bell

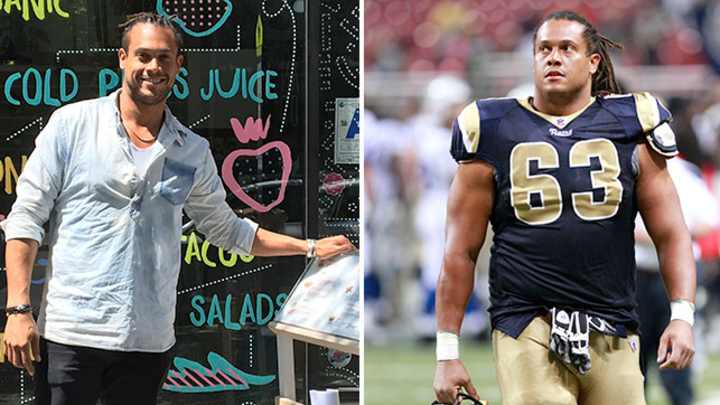

SAN DIEGO — One block past the rightfield fence at Petco Park, among craft-brew pubs and $100-a-month fitness studios, one of the newest establishments, a vegan and raw-centric cafe, thrives. On a recent Wednesday afternoon, sun bursts through open doors. A food blogger roams, snapping shots of the newly bolstered deli menu ($12.95 tuna poke bowls) as a high-def television scrolls through slideshows of the Amazon. The founder, a broad but toned man with dreadlocks wrapped in a bun and a soft chambray shirt, adjusts the potted plants affixed to the wall while keeping an eye on idle customers. “I feel like it’s taking too long,” he says. “I don’t want anyone to wait more than 10 or 15 minutes.” Slightly agitated, he scoots behind the counter to expedite, scooping seaweed salad onto a biodegradable plate.

This is about as stressed as you'll find Jacob Bell these days. Between daily yoga and living along the coast, the 35-year-old embraces a lifestyle of tranquility. Sol Cal Cafe, which opened in October 2014, is his oasis.

“In my previous job, I was a warrior,” Bell says. “It’s good to be a fighter when you’re in war. But now, it’s a time for peace.”

Bell reached that epiphany abruptly. Four years ago, he was sitting on his couch, watching television when breaking news flashed on the ticker: San Diego’s beloved football star, Junior Seau, had pointed a gun to his own chest and pulled the trigger. Bell called his parents in Ohio. “I’m done,” he told them. “I just can’t play in the NFL anymore.”

Jacob Bell was Chris Borland before Chris Borland. A left guard with the Titans, then Rams, Bell had signed a free-agent contract with Cincinnati in 2012. One month later, at age 31, he quit. Bell never put on a Bengals uniform.

At the time, he was considered an extreme outlier. CBS This Morning lauded Bell as “the first player to announce his retirement because of fear playing the sport he loves would result in long-term brain damage.”

The publicity paled in comparison to what followed Borland’s watershed announcement last year. While their rationale for leaving while still valued as commodities is nearly identical, Borland was just 24 and had played only one season with the 49ers. Bell was about to begin his ninth NFL season, had made 100 starts and had already cashed in (his six-year, $36 million deal with the Rams in 2008 included $13 million guaranteed). The deal with the Bengals was for $825,000, the veteran’s minimum. “At the time I retired, I hadn’t heard of Jacob Bell,” Borland said in a phone interview last week, noting the story sounded familiar, especially since Bell, like Borland, is from football-crazed Ohio. “But I think anytime more information becomes available, the landscape changes. Each individual retirement is different. I don’t know if there’s a community of players advocating for early retirement, or even community in general because there aren’t that many of us.”

* * *

Bell says he had three or four documented concussions. “Everyone in the NFL is aware that what they're doing could potentially be bad for their health,” he says. “If you’re banging your head for a living, you have to figure at some point you’re going to pay for it. But I took action when a direct link became defined. There were no ifs, noes, maybes about it. The NFL was in denial about it at the time, but the news was out there.” As headlines of former player lawsuits and budding CTE research piled, Bell’s passion dwindled.

Still, he signed with the Bengals in free agency; Cincinnati was a manageable drive for his family in Cleveland. He loved the camaraderie in the locker room.

Then Seau’s suicide happened. Bell had played against the linebacker, and “was kind of cool with him, we hung out a couple times.”

“It just hit home so hard,” Bell says. “I was terrified. I was terrified to play, terrified of what might happened to me. Alzheimer’s is so selective. CTE is so selective. Why quit if you’re not feeling anything? You might not feel it for 20 years, 30 years. Well, for me, the risk and reward, at that point in my career, it just didn’t match up.”

Bell alerted his agent, who said he needed to call Marvin Lewis. “S---,” Bell said, wary of an uncomfortable conversation. At first, Lewis tried talking his new free agent out of it. Just come to training camp, the coach said. Once you walk away it’s hard to come back. The bargaining didn’t resonate, and Lewis accepted Bell’s resignation.

“He was surprisingly cool about it,” Bell says, recalling Lewis’s parting words: “If you got to that point where this is what you’re thinking, then I’m sure this is what you want to do, because it takes a lot for someone to come to that.”

In less than a week, Bell sold the furniture from his St. Louis home and booked a one-way ticket to Southern California. Former teammates were universally supportive, he says. He fielded more media requests than he had over the course of his eight NFL seasons combined. “The thing on my mind then was, how do I find my purpose in life?” he says. “I identified as a football player since I was a kid. That’s who I was and that’s something I didn’t have anymore. It wasn’t easy. It still isn’t easy. I don't think it ever gets a lot easier.”

* * *

Bell, whose playing weight was 304, shed 50 pounds in the first four months of retirement. He had eight surgeries in his career—two in college, six in the NFL—and swore off heavy squats and lifts the moment he retired. “The workouts in the NFL are pretty archaic, and really damaging for the joints,” Bell says. “I think they could prevent a lot more injuries by introducing more functional movements. You don’t need the big weights to be strong and healthy.”

Bell was as light as 220 pounds, and now sits comfortably at 240. He boasts being in “fantastic shape” but “I’d get crushed if I lined up now.” Besides yoga, Bell enjoys cardio and high-rep, low-intensity weight classes “the type with 25 girls, two guys, and the girls are just crushing it. Like, there’s a sixth-month pregnant lady next to me, not even sweating.” He doesn’t regret leaving, but considers his alternate ending. At 35, it’s not unreasonable to think he’d be gearing up for another training camp. “I miss it,” he says, “But mostly I miss the people.” He stays in touch with a core group of ex-NFL friends. One is flying out to San Diego this week to buy his car.

“Sometimes I’m wary of speaking out against the NFL, you don’t want to bite the hand that fed you,” Bell says. “I watch every game. I sit there, it's like Christmas every Sunday morning.”

When he first retired, Bell considered broadcasting. He also wanted to host camps, or coach—just stay connected to the sport.

“But the longer I’ve been out, the more information that has become available, I become less attached,” he says. “I’ve had eight different surgeries, multiple concussions, and the league makes you jump through hoops just to claim benefits or get psychiatric treatment from damages we sustained on the field.”

Bell wonders why it took four years for another proactive retirement, but he gets it. “The money seduces you,” he says. “It’s addictive.”

Borland says that in the past year, about a half dozen current players have reached out to discuss the possibility of walking away. “There wasn’t a flood of guys immediately, it has kind of been a good conversation every month or so,” says Borland, who last week began an internship in the mental health sector of The Carter Center at Emory University. ”The NFL has done some things as a league that someone that is apprehensive of the game or is just a bystander would find reprehensible. I’m not that emotionally charged about it, though. I’ve had a good experience with the 49ers, and everyone I worked and played with. At the same time, you’d have to have your head in the sand to follow football and not be disturbed by some of the stuff going on.”

Borland spent a year traveling before settling on his next move, at the Carter Center. Bell, too, needed time to breathe. Sol Cal Cafe was an organic investment, as Bell’s family ran an Italian restaurant in Cleveland and he grew up running around the kitchen (and getting kicked out by line cooks). Bell became passionate about eating clean toward the end of his playing days, and especially since moving to Southern California. When his friend saw a reasonable listing adjacent to the baseball park, the two decided it was a good investment.

Running a small business has its challenges—Bell recently hired a private business coach—but plenty of rewards. This afternoon, as a steady flow of lunch-goers leaves smiling, Bell exudes calmness. The cafe uses Bell’s NFL connection in some of its marketing, and though Bell says he thinks people recognize him, they rarely say anything in the one hour a day he spends at the cafe. “It’s funny, because then I’ll go to a bar, and people with a little liquid courage will shout to me: ‘You’re the guy from SoCo!’” His new identity, it seems, is starting to stick.