What It’s Like to Get Called into the Principal’s Office

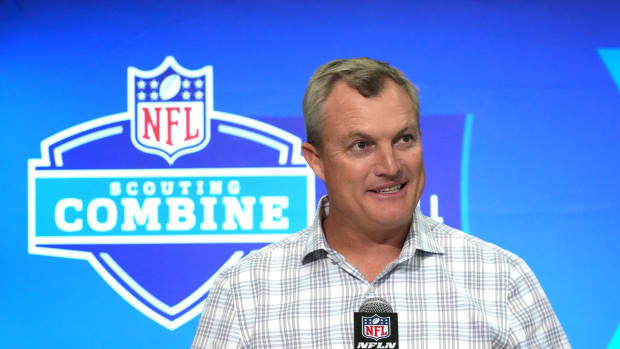

A letter appears in the player’s locker one day, if the season is in progress. In the offseason, it arrives at his home, via FedEx. His agent and the union receive copies via e-mail, too. The NFL Shield is there at the top, and it’s requesting that the player report to the league offices at 345 Park Avenue, in midtown Manhattan, for a meeting with the commissioner, Roger Goodell. Attendance is mandatory. Sincerely, NFL senior vice president Adolpho A. Birch III. The player has been officially summoned to the NFL equivalent of the principal’s office.

He arrives to New York the night before his meeting and ducks into an Italian restaurant near his hotel to huddle with his lawyer and strategize. He gets his story straight, what he wants to tell the commissioner, how he might answer certain questions. He worries about his message coming across the right way. He wonders how Goodell will respond.

The next morning, as he approaches the league office, he and his lawyer are met by a swarm of media members. He’s turned from a football player into a paparazzi target. The cameras snap. Don’t look so menacing, his lawyer had told him. Try to smile. Look relaxed. Relaxed? He just wants to get inside. How are these guys walking backwards filming me?

He is directed to the sixth floor, where he walks into a waiting area with pearl-white seating. In one glass case is the Super Bowl trophy. Behind it is another glass case displaying every Super Bowl ring. Magnifying glasses are there to get a closer look, as if they are some precious artifacts, which, here, they are. Behind the receptionist’s desk, a giant TV plays the NFL Network, showing pundits discussing news from around the league—such as the very discipline meeting the player is about to enter, the case reported in the media for weeks.

Now the player has to wait while a conference room is prepared, and those 10 to 15 minutes feel like forever. He’s transported back to middle school, sitting outside the principal’s office, waiting, waiting, waiting, a million things running through his mind.

This is a feeling several players have experienced since Goodell became commissioner 10 years ago. When Goodell took office, his predecessor, Paul Tagliabue, had been considered passive when it came to player discipline. But as the league developed into a multibillion-dollar entity, Goodell felt it was his duty to police the players and “protect the shield,” the NFL’s image, as he put it. Spygate. Bountygate. Deflategate. All the –gates. Player discipline, though only one part of his job, has become something for which he will be remembered.

And so, sitting across from Goodell in one of these discipline meetings can give a unique look at him as commissioner. Like a principal, Goodell wants the honest truth, for you to express remorse and not to talk back. Whether you accept Goodell’s point of view could play a role in determining how the meeting will go. He can get loud and demonstrative when he’s making a point. Or he can put an arm around you and walk you back to class. Many players find his demeanor condescending and his punishments oppressive. Others think he is tough because he cares and wants to help rehabilitate you. Sometimes near the end of the meeting, after he’s heard the player’s side and is mulling it over, Goodell will deploy an old principal’s trick.

Tank Johnson visited the commissioner in 2007, after he had multiple off-field incidents, including having gun charges being brought against him. Johnson had argued to the commissioner, in part, that the legal system had tried to make an example of him.

“Tank, how many games do you think you should be suspended?” Goodell asked.

Johnson looked Goodell in the eye. “None,” he said.

“In this case, I agree with you,” Goodell said, according to Johnson. “But I have to suspend you to uphold the integrity of the National Football League.”

* * *

Players get popped for on-field infractions, off-field incidents, using substances of abuse or performance enhancing drugs, or even deflating footballs—and the majority of them don’t come to the league office or meet with Goodell at all. There are collectively bargained policies in place governing players who are caught using PEDs or recreational drugs. If a player gets cited for an in-game incident, he might meet with a football operations staffer. When a player violates the “personal conduct policy” for something off the field, he will often meet with Birch, if anyone, and Birch will simply brief Goodell on the situation and the action the league is taking.

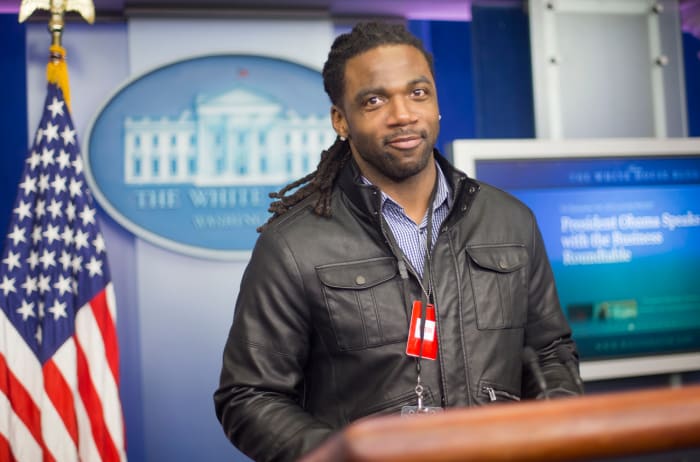

Birch estimates that, in Goodell’s 10 years, the commissioner has only attended about 10 to 15 formal face-to-face player discipline meetings. Usually Goodell takes the higher-profile cases, such as the one involving Donté Stallworth in 2009. Stallworth, a receiver with the Browns at the time, had struck and killed a man while driving under the influence in Miami, pleaded guilty to DUI manslaughter charges, and had spent only 24 days in jail as part of his plea agreement.

About a month after Stallworth was released from jail, Goodell met with him in New York. Goodell sat on one side of the conference room, next to Birch and the league’s legal consigliore, Jeff Pash, the two men who often accompany him at these meetings. On the other side Stallworth sat alongside an assortment of people: his mother; his close friend Steve Boucher; Rebkah Howard, a public relations representative; and two lawyers, one of whom was David Cornwell, a high-powered attorney who had dealt with Goodell in the past.

• YOUR VIEWS ON ROGER GOODELL? Send your thoughts and opinions on the commissioner and the state of the NFL to talkback@themmqb.com.

Birch ran the meeting, as he usually does, making sure it was orderly, so that Goodell was free to listen, and speak when he saw fit, as Stallworth and his team made their case. Stallworth walked them through everything he did that day, from the moment he woke up, and Cornwell explained the context of the accident, and why Stallworth had received a relatively light sentence, which had created some public outrage. Cornwell brought out the police report, crime scene photos and a video taken at the scene that was not released to the public. It showed the accident in its gruesome entirety and supported the lawyer’s contention that the victim had suddenly appeared in front of Stallworth’s car while rushing to catch a bus, and that there was little Stallworth could have done to avoid hitting him, no matter if he were drunk.

Finally, Goodell piped up.

“I can’t remember if he cursed or not,” Stallworth recalled. “I don’t know if he did because my mother was there. He basically said, ‘Listen, I don’t give a shit about the legal side. I want to know that you understand the irreparable harm that you’ve done to this family, and the stain that you’ve put on the NFL, and yourself and your own family.’ ”

Stallworth’s lawyers had touched a nerve. “He does not have a high tolerance for over-lawyer-fication, so to speak,” Birch says of Goodell. “I’m an attorney; we value our services. But sometimes I do think things get bogged down over legal arguments back and forth. That will kind of set him off, I’ve seen. At least it frustrates him.”

Stallworth rebuilt his career and his life after his jail time and league suspension.

Pablo Martinez Monsivais

As the meeting went on, Stallworth’s mother, his friend, and Howard all spoke on his behalf, about his character, how this was not typical of him. Then as everyone was leaving, Goodell pulled Stallworth aside to speak to him privately, one-on-one. This was another technique of his, an attempt to peel back the legal stuff and connect with the player on a more human level and maybe ensure that the player understands where he’s coming from.

Goodell reiterated he was “disappointed” in Stallworth’s actions. He emphasized again the gravity of the situation. He told Stallworth that the court ruling would have no bearing on how Goodell punished him now. “We’re not tied to the legal system,” Goodell told him.

Stallworth flew back to Florida. After replaying the meeting over and over in his head, he decided he needed to see Goodell again. He didn’t think he had expressed how remorseful he truly felt. A few days after the initial meeting, Stallworth flew back to New York unannounced and went to straight to the league office. When Goodell’s secretary said his schedule was packed, Stallworth sat there reading a book called The Holy Man, steeling himself to wait there all day if he had to … when Goodell spotted him on his way to another meeting. Not long after, Goodell cleared his schedule and invited Stallworth into his office, a cozier setting.

“Before you walk in this office,” Goodell told him, “you’re not a player and I’m not the commissioner. You walk in here as a man who’s talking to another man. I want you to know that walking in here. We’re not commissioner and player. We’re man and man.”

In the middle of Goodell’s day, they spoke for about an hour. Stallworth said his part, and Goodell stated he wanted Stallworth to use the accident as a platform to become an advocate against drunk driving. Goodell also opened up to Stallworth about hardships he had overcome in his own life, things that had not been made public, things Stallworth wasn’t sure many other people knew. Goodell asked Stallworth what he would do, if he were sitting in his chair. Stallworth had thought there was a chance he would be banned for life. He told Goodell then that he would suspend himself “at least for a year,” which is what Goodell would eventually do. As Stallworth left the room, this time Goodell went in for a hug.

* * *

Just before Roger Goodell went to testify in a hearing involving Ray Rice, he found himself next to Peter Ginsberg, Rice’s lawyer, in the bathroom, at the urinal. Ginsberg joked, Roger, look, we’ve got to stop running into each other like this. And Goodell didn’t laugh, according to Ginsberg. Didn’t smile. Not even for appearances. He just silently left the bathroom.

Of all the lawyers Goodell had dealt with, Ginsberg was perhaps the one he despised the most. Ginsberg had represented players in two of the NFL’s highest profile player-discipline cases—Rice in the elevator incident with his fiancée, and Jonathan Vilma in the Bountygate scandal—and was front and center in the media, attacking Goodell and the league and its practices. Ginsberg knew how to make Goodell squirm, his face turn red. The first time Ginsberg represented someone in front of Goodell, he pleaded for leniency for his client, and Goodell stood up, wagged his finger, and said, “Don’t you ever lecture me again!” Later, during a Bountygate hearing, Ginsberg spoke for 45 minutes, uninterrupted, lecturing the room on the flaws in the NFL’s case, and then he left the room, bringing Vilma with him, robbing Goodell of any chance to respond.

A league official disputed Ginsberg’s account of his interaction in the bathroom and the first time they met. The official indicated that Goodell had not stood and wagged his finger.

Nonetheless, Ginsberg was the lawyer players hired when they needed someone to stand up for them against the commissioner. Rice had spent three hours in a conference room at Ginsberg’s office, getting emotional discussing his case, trying to convince him to take him on as a client. (A source close to Rice disputed this.)

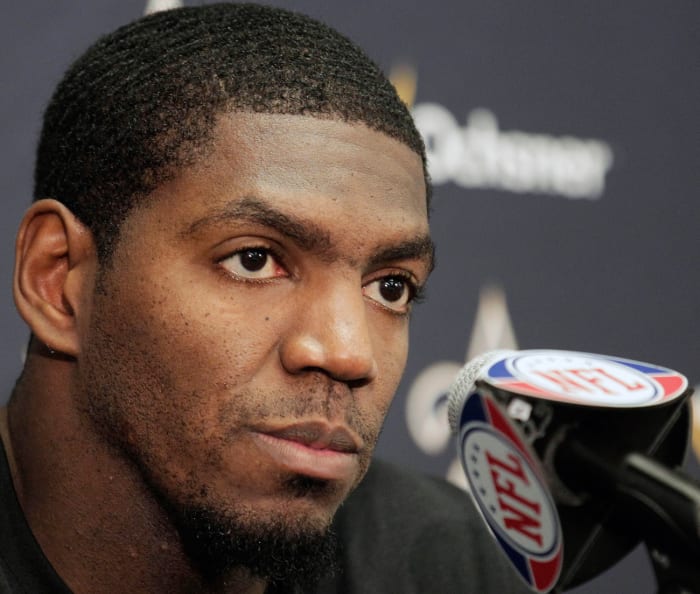

Jonathan Vilma had his Bountygate suspension overturned by Paul Tagliabue, whom Goodell appointed to hear the appeal. Vilma’s subsequent defamation lawsuit against Goodell was dismissed by a judge.

Bill Haber/AP

Ginsberg is sitting in that same room now, with a courtroom drawing of Michael Vick on the wall, describing what it’s like for him sitting across from Goodell. In his experience, he says, Goodell is cold and judgmental. He believes the commissioner is swayed by public opinion and has his mind made up before the meeting starts. It doesn’t help that Goodell’s punishments at times seem arbitrary. Ginsberg theorizes that Goodell has cracked down on certain players to compensate for not already having that protocol in place, for dealing with social issues. Like Ray Rice and domestic violence. Or Adrian Peterson and child abuse. Both of those players were suspended indefinitely, as the league decided what to do about them.

The same league official pointed out that the commissioner takes into account precedent, the individual player’s past record, and whether the player cooperates, for which there is punishment. The official pointed out how, in December 2014, after the Rice and Peterson cases made national news, the league took a step toward installing protocol, rewriting the personal conduct policy to say a player would receive a six-game suspension for a wide range of violent crimes including domestic violence and child abuse, on the first offense.

Now, what would Ginsberg advise a client who was summoned to meet with Goodell? For one, Ginsberg would tell him not to say anything that’s going to be difficult to answer for in future litigation, because there was always a chance a judicial process may follow.

“What Roger looks for is somebody to agree with him. Or to beg forgiveness,” Ginsberg said. “It’s very difficult to have a genuine, authentic disagreement with Roger.

Ginsberg went on: “If you’re not willing to do a mea culpa and get down on your knees and cry a little bit, and convince Roger you’re a better person for having been through the experience … it’s difficult to walk into one of those meetings feeling very optimistic.”

* * *

Anthony Hargrove visited the league office about four or five times over the course of his eight-year NFL career, for when he was a heavy user of alcohol and cocaine and, later, when he became a centerpiece of the Bountygate scandal. Whenever he came to New York, the Players Association would arrange his travel and hotel accommodations. Sometimes the union would put him up in the famous Waldorf Astoria.

Hargrove took a warm bath, hung around the room in his Waldorf Astoria bathrobe, and called his brother. “Hey, bro, you won’t believe what I’m doing…” He ordered the chocolate strawberries from room service and strolled through the lobby, passing the sparkling jewelry store and the restaurant, the people laughing, getting a whiff of the steaks cooking.

“Just the smell of … the upper echelon,” he said.

But over time, Hargrove realized, if the union had gotten him a room at the Waldorf, he “was going to be in for a fight” with the league. Those strawberries were his last supper.

Anthony Hargrove firing up his defensive teammates before the 2009 NFC Championship Game.

Dave Martin/AP

This time, Hargrove was there for another hearing in the Bountygate scandal. Goodell had initially suspended Hargrove eight games, accusing him of lying to league investigators, which, in Goodell’s eyes, might as well have been a cardinal sin. Goodell seemed to take personal offense when he felt a player was being dishonest with him. He cited Hargrove for “conduct detrimental to the NFL.”

The Bountygate case had taken another turn. Goodell had already denied Hargrove’s initial appeal, and an appeals panel had followed by temporarily vacating the suspension, and now Hargrove was back to state his case once more, in front of Goodell, who would rule again whether to uphold the very suspension he had handed down himself.

Hargrove prepped accordingly. He asked the other players in the Bountygate scandal how their hearings had gone. He studied Mary Jo White, the former prosecutor Goodell had tabbed to review the case, and her interview style. Hargrove had visited the league offices so many times he even knew the security guard and where the hearing would take place.

• THE FANS SPEAK: NFL die-hards on whether Goodell is good for football

Then Hargrove got on the elevator was directed to go down to a lower level. Down? The elevator kept going and going, descending into what Hargrove said “seemed like hell.” His heart sank into his stomach. This wasn’t what he had planned for. Hargrove walked into a large windowless room, and there was Goodell, standing, reaching out to shake his hand, and there was White, and what felt like an army of faceless people who didn’t look friendly.

Hargrove couldn’t breathe. He felt as if he were going to have a heart attack. He started doing breathing exercises as he took his seat, giving himself a pep talk, the way he might before a big game. This felt bigger than a game. “I was fighting for my career against a machine, or a monster,” Hargrove said. “They have the power to end your career!”

Recently, James Harrison tried turning the tables on Goodell. When the league started investigating the veteran linebacker over allegations in an Al Jazeera report that he used PEDs, he posted a message on his Instagram that looked like a ransom note, calling Goodell a “bully” and saying he would meet with league investigators only if the interview took place in his own home, where he would feel more comfortable.

The league sometimes changes the locations of player discipline meetings in an effort to avoid media attention. It will hold meetings elsewhere in Manhattan and have players use side doors. Once, when the location was revealed, the meeting was moved, then moved again. Michael Vick met with league officials at a nondescript office in a small town in New Jersey. Ben Roethlisberger had one of his meetings in a conference room at the Westchester airport.

The room in the basement where the NFL took Hargrove was what a league official described as a “multipurpose room,” a place used “when there is a need for privacy away from the rest of the building.” Tom Brady had his Deflategate hearing there.

In Hargrove’s case, Mary Jo White led the charge, pummeling him with questions. “She would ask the same kind of questions over and over and over,” said Phil Williams, Hargrove’s agent, who was in the meeting. “She kept trying to trap Tony.” Williams wondered when the two union lawyers there would step in.

Goodell sat quietly, Williams said, “until he felt like there might be blood in the water” and thought White was about to catch Hargrove in a lie. Goodell would lean forward in his chair quickly. His eyes would get excited. Then, Williams said, when Hargrove would talk his way out of it, Goodell would get red and slide back in his chair.

• BRANDT ON GOODELL: Our Business of Sports columnist on the policies that have defined his tenure

At one point, Hargrove requested that White just reference the interview he did with a league investigator named Joe Hummel in 2010, at the outset of the Bountygate affair. The NFL side of the room seemed startled by that. They took a recess and huddled. Then, according to Hargrove and Williams, the league said there was no record of the interview and that another man had conducted it. What? Hargrove had been sitting there with Hummel, face to face. (A league official maintains the stance Hummel was not the one who interviewed Hargrove.) There, in a windowless room in the basement of the NFL offices, Hargrove felt hopeless.

“It became clear to me,” Hargrove said, “it was going to be difficult for me to prove myself innocent because they were going to conjure whatever truth they needed to make it believable to the public. That was the hardest thing to swallow. You feel like you’re screaming at the top of your lungs, and no one’s listening.”

* * *

After the meeting in his office, after Goodell makes up his mind, he writes the player a second letter on league stationery. He admonishes them for their actions, outlines his thought process and notifies them of the punishment. His tone reflects how seriously he takes each situation. In his letter to Adrian Peterson, Goodell threatened that if Peterson violated the personal conduct policy again, he would face possible “banishment from the NFL.”

In some instances, Goodell continues to stay in touch with the player and develops a relationship. Goodell kept up with Stallworth and spoke to owners on his behalf when he was reinstated, which helped him play in parts of three more seasons. Goodell stayed in contact with Tank Johnson, too, and now Johnson works as an intern in the league office.

Vilma, on the other hand, was never the same player after Bountygate. The entire league seemed to blackball Rice. And Hargrove never played another snap; he might as well have been radioactive; his career ended a month before his 30th birthday, while he was still in his prime.

Now Hargrove has found new direction. He’s finishing his bachelor’s degree in special education at Rend Lake College in Illinois, with help from a scholarship from the NFLPA. He’s teaching high schoolers at an education center about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. “Basically it’s accepting where you’re at now,” Hargrove explains. “Being able to defuse the situations that are in your life…”

“Something the NFL helped me learn!” he adds, letting out a deep laugh.

• YOUR VIEWS ON ROGER GOODELL? We’ll wrap up Goodell Week by compiling and posting the most thoughtful feedback. Send your opinions on the commissioner and the state of the NFL to talkback@themmqb.com.