Column: Youth football a defining issue with no easy answers

Kevin Turner started playing football when he was 5. If his father had it to do over again, he might've insisted that his son wait a few years before taking up the game he loved so much, the game that that would eventually turn his brain to mush and snuff out his life far too soon.

Tellingly, though, Raymond Turner wouldn't have prevented Kevin from playing football, even when looking at it from the most awful perspective of all: a parent who buried his child.

''I don't regret that he played football,'' Raymond Turner says. ''I just wish he played in a safer way.''

And that's the conundrum facing millions of football-loving parents across this country. Do they let their children play? And, if so, how old should their kids be when they first put on a helmet and pads?

There's no right and wrong in this debate but the stakes are enormously high, from the future of the game to the long-term health of those who play it.

While football is much safer now that it was when Kevin Turner took his first snap, it will always come with a significant risk of serious injury.

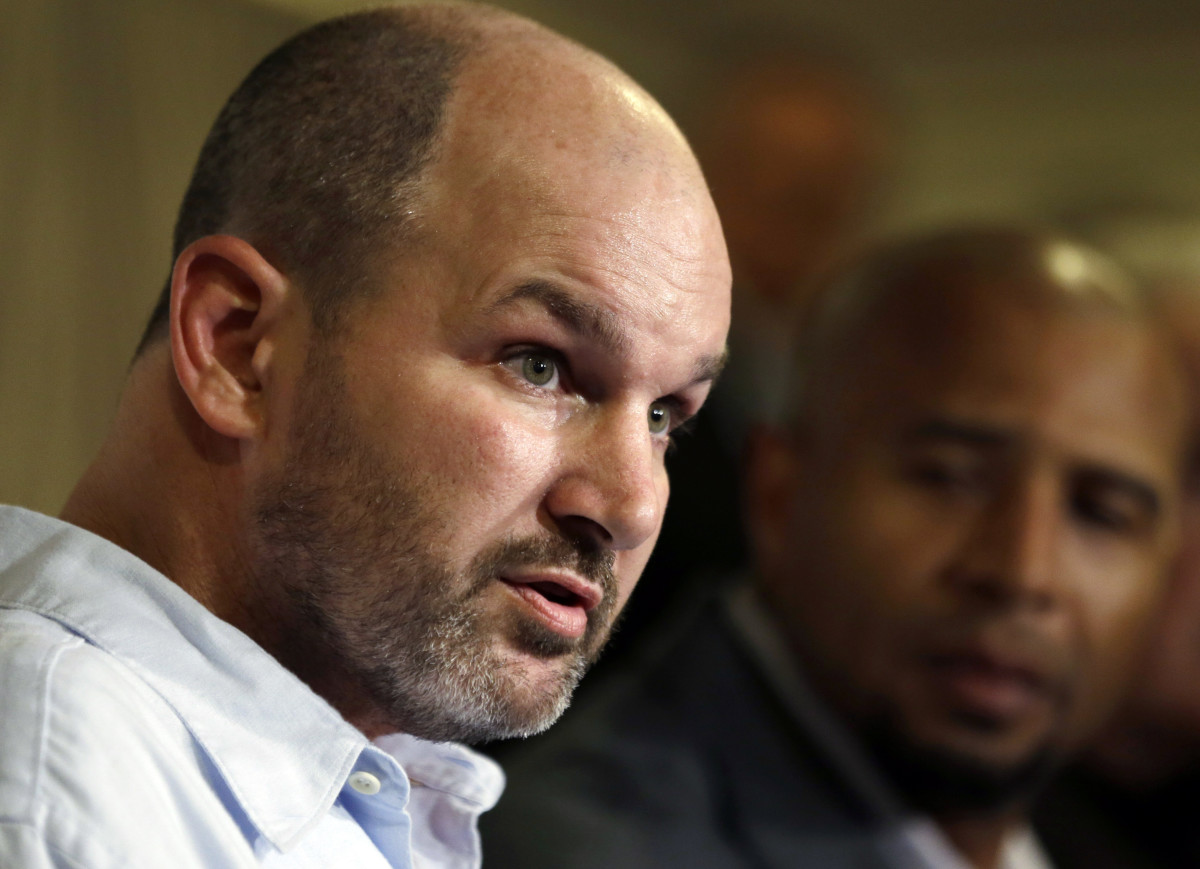

At Boston University on Thursday, experts said the former Alabama and NFL fullback had the most severe form of chronic traumatic encephalopathy they've ever seen in someone his age. Turner was 46 when he died in March from Lou Gehrig's disease, which robbed him of his body and was likely caused by CTE.

Now, on to the next stage in this debate.

Chris Nowinski, a founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, is leading the charge to keep young children from playing football, at least the blocking and tackling kind. He says Turner's death is just the latest in a persuasive body of evidence that kids should stick to flag football or seven-on-seven - essentially, a touch version without linemen - until they get to high school.

''This isn't about picking on football,'' Nowinski says. ''I'm a football guy. But I'm very happy my mother kept me out until high school. I wanted to play earlier. I wanted to hang out with my buddies. I wanted to join the seventh-grade team. But she wouldn't let me.''

Nowinski, who went on to play football at Harvard before a career in professional wrestling, said it only makes sense that someone who delays the start of their football career by nine years - from 5 to 14, roughly the time they're starting high school - will significantly reduce the risk of long-term health problems. And, since only a small percentage will keep going after high school, we can expect a whole generation of much healthier ex-players down the road.

''We have to accept that football is dangerous to the brain,'' Nowinski says. ''It's like smoking and lung cancer. If you smoke fewer cigarettes per day and smoke for fewer years, the risk of cancer goes down. We can apply that same knowledge to football. If we shorten the years we take off the front end, and limit hits to the head through reforms like we've seen from the NFL to colleges to high schools ... then suddenly, the future is tremendously brighter for football players. That's what Kevin Turner taught us.''

Jon Butler sees things differently. He's the executive director of Pop Warner, the nation's most prominent youth football organization, where kids can begin playing tackle football at age 5.

To its credit, Pop Warner has taken major steps in the last several years to reduce the risk of injury, such as limiting contact to no more than 25 percent of the practice time, requiring coaches to take part in programs design to teach safer tackling techniques, and prohibiting full-speed drills in which the players line up more than 3 yards apart. This year, kickoffs were eliminated for the three youngest age groups.

Butler says his organization has informally tossed around the idea of banning tackle football for young children, but found it would likely prompt nearly all players to simply leave for a non-Pop Warner-affiliated league that allows physical contact - and may not have many of the same safety measures.

Also, he stands by the value of teaching kids proper blocking and tackling techniques at a young age, insisting that makes the game safer as they get older.

''Flag football is fine as far as learning the techniques to be a quarterback or running back or wife receiver,'' Butler says. ''But if you end up being a lineman ... you're not learning much of anything. Blocking and tackling techniques need to become instinctive and intuitive.''

Both Nowinski and Butler make a compelling case, one that should be debated in the privacy of every household where parents are faced with this potentially life-altering decision.

Even then, it doesn't get a whole lot easier.

Dr. Wayne Gordon, director of the Mount Sinai Brain Injury Research Center, said there is no definitive proof of when a young brain is at its most vulnerable state. He described the idea of banning kids from playing tackle football until they get to high school as ''a pretty arbitrary cutoff.''

Then he was asked if children of any age should be allowed to play football.

''Obviously, kids want to have fun,'' Gordon says, measuring his words. ''But they don't need to tackle in order to have fun. So I would basically not let children play tackle football.''

This could be one of the defining issues of our times.

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers.

---

Paul Newberry is a sports columnist for The Associated Press. Write to him at pnewberry(at)ap.org or at www.twitter.com/pnewberry1963 . His work can be found at http://bigstory.ap.org/content/paul-newberry .

---

AP NFL website: www.pro32.ap.org and www.twitter.com/AP-NFL

---

AP Sports Writer Jimmy Golen in Boston contributed to this report.