Travis Kelce Living a Very Travis Kelce Life

Those who know Travis Kelce best are prone to employ his name as an adjective. Cutoff denim, for instance, is very Travis. A cream Gucci suit, splattered with red drawings of a pirate Donald Duck and paired with a Smokey the Bear-style hat (his outfit at a recent charity fashion show)—that was so Travis. The most Travis thing about Kelce’s Kansas City apartment might be that he employs one of his two bedrooms as a third walk-in closet, depository for various snake-collared shirts and Christian Louboutin kicks.

But when I meet Kelce in his apartment building’s lounge, he is clad in an unexpectedly un-Travis outfit: white Nike tee and red gym shorts, white Nike Prestos and a black compression sleeve around his left leg. I toss out an innocuous question about whether he’s lived in this building, in the downtown Power & Light District, for all four of his years as a Chiefs tight end, and he does a fairly Travis thing, letting slip a truth he’d probably rather not tell through a smile that disarms it.

His first two seasons in town he lived down the street. But, he says, “my neighbors didn’t like me.” Kelce missed just about his entire rookie year after having microfracture surgery on his left knee, which made him a 24-year-old with an abundance of money and no shortage of free time. Thus followed raucous nights that began and ended at Kelce’s apartment, which friends loved but which the doctor next door decidedly did not. After a few admonishments from the leasing office, Kelce noted the new luxury building nearby, in which he would be the first tenant of his unit and where he would have floor-to-ceiling windows. “Everything just made sense,” he says. So here he is.

But this is not where he is supposed to be now. Today’s plan was for me to tag along with Kelce on a promotional stunt delivering pizzas for Papa John’s, one of his many sponsors; some lucky local would answer the doorbell, un-scrunch some loose bills from a pocket and look up to see—surprise!—the dancing face of the Chiefs. It would’ve been fun. It would’ve been so Travis.

That face has been popping up in more and more places: on a monstrous video screen in Times Square and in NBC’s Sunday Night Football intro, onstage alongside Carrie Underwood. There was even a short-lived reality dating show on E!, Catching Kelce. Tony Gonzalez, this town’s last megastar tight end, thinks Kelce’s media appeal is obvious: He speaks freely and “doesn’t give a s---.” When I ask Aaron Eanes, Kelce’s manager, why sponsors enjoy working with the 2016 All-Pro, he says, “You can tell Travis gives a s---.” Being Travis, then, means both giving and not giving a s---. So Schrödinger, so Travis.

Kelce is not out there surprising local pizza lovers today for the same reason that he is sporting that black sleeve. Forty-eight hours earlier, in a Week 2 win over the Eagles, he scored a very Travis touchdown, taking a shovel pass from the 18-yard line and propelling all 260 pounds of his 6' 5" frame through the air, lifting off at the five and landing in the end zone while absorbing hits from two defenders. It was one of many plays he is still feeling two days later and, well, he says it would be weird to deliver pizzas with a slight, stiff limp.

The soaring touchdown, however, was only half of what made that Sunday particularly Travis. Earlier in the game he’d celebrated Kareem Hunt’s 53-yard TD dash by running to the Eagles’ sideline and delivering some choice words to a defender. Unsportsmanlike conduct; 15 yards on the kickoff. It was, dating back to last January’s playoff loss to the Steelers, the third straight game in which Kelce’s behavior drew such a penalty. Against Philly, Chiefs coach Andy Reid lit into him on the sideline and afterward said, “He’s got to learn.” K.C. news outlets, meanwhile, bemoaned the very Travis combination of 103 receiving yards and yet another foul for misconduct. On the radio the next afternoon one host described Kelce’s behavior as “what a little kid does.” Someone else compared the tight end to a child who hadn’t outgrown his binky.

When we meet, Kelce has yet to address the subject. Not that reporters didn’t try: Having dodged three postgame questions on the matter, he asked, “Any other questions?” He tells me he anticipated the queries and didn’t plan to address them. He didn’t want to get riled up and say something he might regret. “I just felt like I didn’t owe anybody an explanation,” he says. Which is a very Travis source of frustration. He’s been having to explain himself his whole life.

Travis Kelce entered the NFL in a very Travis way, and for maximum effect I will cede the floor and let him tell the story of the 2013 draft in his own very Travis fashion. “I got a call from an 816 number,” he says. “It just pops up on my phone as Missouri. I had no f-----’ clue Kansas City was even in Missouri—I thought it was in Kansas.” It’s in both. It’s confusing. “I’m like, ‘Nooo, not St. Louis. They don’t look like they have a bright future.’

“I answered the call and it’s Andy Reid,” for whom Travis’s older brother, Jason, had played center in Philadelphia. “I’m like, ‘Hey, Coach! How are you? Sweet!’ He goes, ‘Yeah, listen. Are you gonna f--- this up?’ I was like, ‘Um, excuse me, coach?’ ‘Are you gonna f--- this up? I have the next pick [no. 63] and I wanna know if you’re gonna be the player I need you to be or if you’re gonna keep being this young punk who doesn’t listen to anybody.’ I’m sitting there like, Man, what? ‘Coach, I will be the best player you ever coached. Just give me a chance.’ And he goes, ‘All right, put your brother on the phone.’ ‘What? All right.’ I still have no idea what he said to Jason. I’m assuming they had a mutual agreement, like, ‘If he f---- this up, we’re both kicking his ass.’”

This wasn’t an unfamiliar topic of conversation. In the run-up to the draft, teams grilled Kelce about the red flags on his college résumé, culminating in a moment, described by Kelce to GQ, in which Ravens GM Ozzie Newsome asked, “Son, are you a f------ a------?” Those interrogations stemmed from Kelce’s penchant for scuffling and trash-talking on the field, and from the year he spent away from the college game altogether. That thread of Kelce’s backstory is well-worn: As a redshirt freshman backup QB at Cincinnati he got busted smoking weed and lost his scholarship. Rather than drop out, Travis moved in with Jason—then the Bearcats’ all-conference left guard—and slept on the floor while toiling at a miserable telemarketing gig.

It was a shock to Kelce’s system. “I knew, All right, this isn’t a joke,” he says. Cincinnati allowed him back a year later as a walk-on, on the condition that he switch full-time to tight end, which he hated in part because he went from potentially handling every snap to, in reality, catching just 13 passes in his entire junior season. But he earned his scholarship back, and by the next year, when he caught 45 passes for 722 yards, he was one of the country’s best pro prospects at tight end.

The Giants Showed How to Beat Denver’s Defense

Before his suspension, Kelce says, he’d never worked particularly hard at sports. Which is not to say they weren’t important. He was a restless kid with an active brother two years his elder, which meant he was in the backyard tossing around one ball or another whenever time allowed (and even when it shouldn’t have, as evidenced by his report cards). Travis was talented, even without extra workouts or weight training, and competing with Jason—in everything, all the time—fostered a drive that maximized those talents. Family members tell the story of a Jason-Travis post-basketball brawl in the kitchen that destroyed both an oven and the casserole therein. And there is something revealing in how Travis describes learning to block after moving to tight end. “I was ready to hit somebody in the mouth,” he says, “just like my brother’s been hitting me in the mouth my entire life.”

The Kelce boys starred at Cleveland Heights (Ohio) High, Jason as an all-league linebacker and Travis as a dual-threat quarterback. By then, what might charitably be called Travis’s on-field zeal was fully developed. (It has since “gotten better,” Kelce says.) In youth hockey and lacrosse he could have established residency in the penalty box, and his parents tacked on hours by making him volunteer at the Salvation Army.

The edge forged in forever battling his older brother cut both ways. Here Travis volunteers just one anecdote (from a robust archive) that he finds suitable to share. At Heights High his basketball team was once picked to play in the local cable game of the week. Travis knew everybody—or, at least a teenager’s version of everybody—would be watching. But then, in overtime, he picked up his fifth and final foul, and “I lost it,” he says. “Absolutely lost it. I started motherf-----’ every ref there. Threw a temper tantrum.”

At home that night, watching the replay on TV, he saw his meltdown and put his head in his lap. “To watch yourself flip out like that and look like you have zero control—it’s not where you wanna be,” he says. “But because I play with so much passion, so much fire, that’s kinda where I’ve caught myself being.“

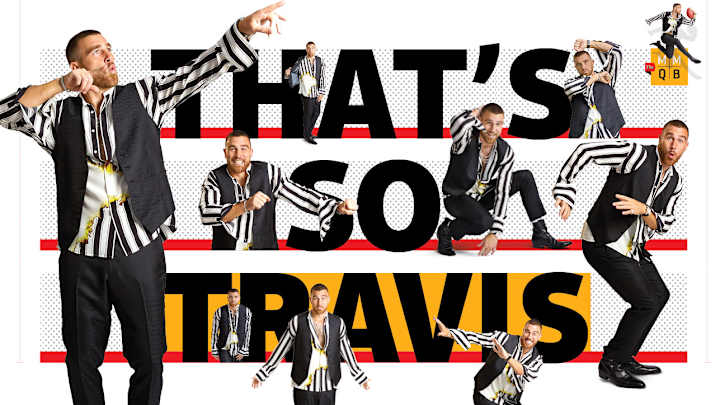

From Kansas City To Hollywood, Travis Kelce Like You've Never Seen Him Before

The first thing everyone saw was the dancing. In August 2014, having recovered from his NFL rookie-year injury, Kelce announced himself to the league by capping a 69-yard preseason TD (including a four-yard dive into the end zone) with the Nae Nae. A month later, he punctuated his first regular-season score with the Shmoney dance.

“He loves attention,” says his mother, Donna. “Always has.” As a kid that meant mugging in home movies and clowning around in class. Even so, Kelce says he’s surprised at the buzz his dances generate, the way they come up in every interview. (Before ours, he wondered aloud to Eanes about the odds that I’d raise the subject.) When Kelce dances, he says, it comes from “how much fun I’m having whoopin’ some tails.”

“Travis truly believes that sports is entertainment,” Donna says. His dances are not some cynical tactic. They are genuine acts of expression. Genuine comes up a lot. In the course of our conversation, Kelce says the word somewhere between nine and 900 times. It’s an important concept to him. Take his dating show. First he had to be sold on the idea—not only did he know nothing about reality shows, but he also needed to be taught to distinguish between the various Kardashians, his new E! network colleagues, before his promotional press tour. What ended up bothering him about the show was how decidedly not genuine it felt. Like the episode where he took a date to a hot dog joint, even though he hates hot dogs. Or the fact that the Chiefs—he won’t specify who, but “the most important people”—urged him to back out of the show, which made Kelce feel like he had to present a team-appropriate version of himself for cameras. Or how, once the show ultimately aired in all its innocuous goofiness, those same important people pretended they’d never objected to it in the first place. There was something irksomely ungenuine there. (Because you’re surely wondering: Kelce and the show’s winner have since split. He courted his current girlfriend, Kayla Nicole, more conventionally—over DMs.)

Of course, Kelce’s public image has not been all dancing and dating. In a 2014 game against the Broncos, cameras caught him making a ... um ... suggestively dismissive hand motion near a referee. (Kelce later corrected the misunderstanding: The gesture was actually directed toward Denver linebacker Von Miller.) Before a playoff game the following season he mocked Tom Brady during warmups. Last year, against the Jaguars, he earned a personal foul for yelling “F--- you!” at an official who’d been ignoring him. Then he threw his towel at the same ref—“I’ll give you a f------ flag!”—drawing an additional penalty and earning him an ejection. And, most prominently, in last January’s division-round loss to the Steelers he cost his team 15 yards when he shoved a defensive back to the ground following a play. Afterward, he ranted to reporters about a crucial holding call against teammate Eric Fisher, declaring that the official who made it “shouldn’t be able to work at f------ Foot Locker.”

Given eight months to think about the last infraction, Kelce sat with NBC’s Mike Tirico before this season’s opener and explained how, now that he’s a team captain, he “can’t just be the young idiot on the field doing immature things.” Two hours after that interview aired, there was Kelce getting penalized for shoving the ball into the crotch of Patriots linebacker Kyle Van Noy. (To be fair, Van Noy did twist Kelce’s face mask.) A week later came the Eagles game and the taunting penalty he didn’t feel like explaining.

Now, in this luxe lounge in his luxe building, Kelce is more candid. I ask, given the subsequent penalty, if he regrets what he said in the Tirico interview. “I probably shouldn’t have said, I’m not gonna get another one,” he says. “It was bold for me to say that. Whatever. I don’t regret it. I really meant what I said.” And the fans’ frustrations? “They have a reason to be upset. It’s fair for everybody to kind of give me s--- for it.”

I ask what he thinks his reputation is. “That I’m very passionate,” he says. “Goofy. And that I have an open heart, that I care about other people.” I start to follow up, but he adds, “Arrogant as well. I forgot to mention that.” Later, when I ask what people misunderstand about him, he brings up that word again: arrogant. “I feel like that’s pushed a lot more than what I really am,” he says. “Anybody who hangs around me and gives me the time of day to have a conversation, they know I’m genuine and I’m not here to be kind of that douchebag.” (This seems to check out.)

Eanes chimes in: “I think people try to extrapolate [from] the way he plays on the field and say, This is who he is off the field.”

“That is a great point,” Kelce says. “Extrapolate. I forgot to use that word.”

Luke Kuechly Is the Poster Child for the NFL’s Concussion Problem

For a player who often loses himself between the lines, Kelce can be keenly self-aware. When Eanes shares a story about overhearing a woman in a restaurant remark that she’s sure Kelce has an ego, Kelce explains how essential an ego is to an NFL player. He reads media coverage of himself, he says, because he wants to know what his parents might be reading about their son. He tries not to let it bother him. He doesn’t always succeed. “When I do take it personally,” he says, “it’s because they’re obviously saying something negative that I don’t want them to say. But I’m giving them ammo to say that.”

Last fall Kelce was at an airport when his phone battery died. He didn’t have a charger so he picked up a book, which he now leaves on a table in his kitchen: The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living. Every page corresponds to a calendar date, and he makes a point each morning of reading that day’s insight and absorbing its lessons. (The entry one day after our meeting is titled “Life Isn’t a Dance.”) The book “tells you, basically, that you can’t control anything other than your reactions,” Kelce says. “You’re the most powerful person in this world when you have to make a decision. And then you have arguably no power at all after that.”

Kelce’s new neighbors seem to like him. They’re a younger crowd, many of whom work in Kansas City’s tech sector, which Kelce tells me is bigger than you’d think. When he gets talking about his adopted home city he can sound like he moonlights on the tourism board. The food is amazing! Have you checked out the arts district? There’s this thing called First Fridays.... He gushes about an old speakeasy a few blocks away, the Phoenix, with “a guy who plays the saxophone, the trumpet and tap dances,” as if he’s discovered the world’s eighth wonder. “Every Friday, four to eight. Every single Friday!”

In the wake of Kelce’s string of boneheaded penalties, Kansas City’s feelings about him can be a bit more complicated. “There’s a love-hate to it, but it’s predominantly love,” says WHB-AM radio host Soren Petro, who’s quick to point out how much he likes Kelce. “[K.C.’s fans] are on the edge of the cliff. They’re still on the love level, but they can see over the edge.”

In the three games after we meet, Kelce will commit zero personal fouls. But you get little credit for that kind of streak. The next time one happens, the finger-wagging will resume, and Kelce knows that. “I play the game with a lot of emotion,” he says. “There are some things that get to me that I’m gonna have to control. And I am working on that. I’m very aware that what I’m doing is unacceptable. At the same time, I’m not going to shy away from anything. I’m going to be who I am. That’s what’s gotten me here.”

Being Travis, after all, is how he kept up with a bigger, stronger, NFL-bound brother all those years. It’s how he survives weekly exhibitions of violence on fields full of even more bigger, stronger brothers, where, as he says, “literally half the stuff we’re allowed to do is illegal in life.” It’s how he could play six games last season with a torn labrum in his left shoulder and still average almost 90 yards in that stretch. It’s how he can take this stage and both strut like Ric Flair in the end zone and also deliver a social message by kneeling during the national anthem, as he did in Week 3.

Being Travis is what has talk-radio hosts chastising him on Monday mornings ... and buzzing about the Chiefs’ reaching their first Super Bowl in 48 years. Sometimes he might be too Travis for his own good, but how can he stop when he believes being Travis is how he got so good in the first place?

Our conversation eventually strays back to that most Travis of TDs, the leaping score against the Eagles. “I’ve always kind of in my head looked at it and said, You know, I could easily dive from the five-yard line,” Kelce says. “So there was no hesitation.”

“Glad you did it,” Eanes says. “But the memes if you had not scored?”

“Oh, it would’ve been hilarious,” Kelce admits. “Any publicity’s good publicity. You gotta have fun with it, man.” Then he shoots me a smile and winks.

Dan Greene is a writer and reporter for Sports Illustrated. He has been with the magazine since his internship in 2010. He lives in Brooklyn and primarily writes about college basketball.