Why the Pro Football Hall of Fame Voting Process Is Broken—and How to Fix It

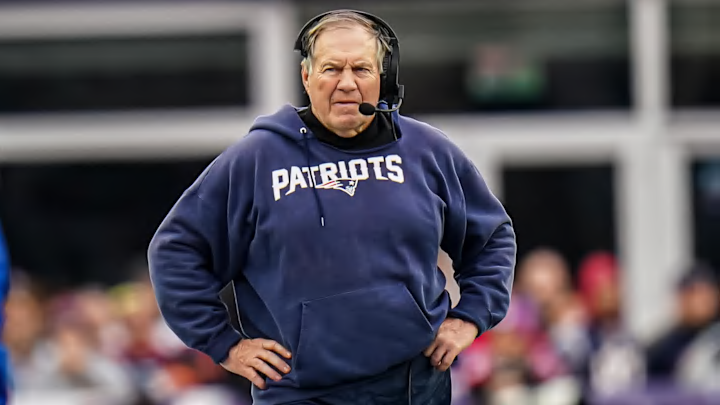

Bill Belichick obviously should not have to wait in line to get into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but at least he has company.

Bill Walsh was not elected on the first ballot. Bill Parcells waited four years. But the problem goes far beyond coaches who should have sailed in. The entire selection process is a delay of game penalty.

Michael Strahan and Michael Irvin both had to wait a year. The last time a center was elected on the first ballot was 1987. No tight end was elected on the first ballot until Tony Gonzalez in 2019.

When the NFL released its 100-player 100th anniversary all-time team in 2019, Alan Page, Mike Haynes, Dick “Night Train” Lane and John Mackey were all unanimous selections. None of them were elected to the Hall on the first ballot.

Far too many players on that all-time team should not have had to wait but did anyway: Marvin Harrison, Dwight Stephenson, Mike Webster, Lenny Moore, Art Shell, John Randle, Randall McDaniel.

Hall voters take the job seriously. But they are hamstrung by a system that artificially limits the number of Hall of Famers per year—and places everybody in the same bucket.

As others have noted, Belichick is in the same category as both “contributors” like Robert Kraft and players from the pool of senior candidates. Voters could only vote for three from that category—and so they were forced to choose between Belichick and deserving people who have waited much longer. Belichick’s case is stronger than the others’, but as my friend Vahe Gregorian of The Kansas City Star explained last week: Belichick will get in, but for other senior candidates, this might be their last shot.

That process needs to be fixed. But the whole process needs to be fixed.

Every year, voters select 15 players as finalists, regardless of position. Each class is capped at five players, not counting senior candidates. It’s simplistic and silly. For an entity that exists to celebrate pro football, the Hall of Fame shows remarkably little understanding of it.

Pro football is a highly specialized sport. Lumping everybody together regardless of position is preposterous. This is not how recognition works in any other aspect of the sport. Imagine if the All-Pro team consisted of the 30 best players regardless of position.

The NBA’s maximum-salary system is the same for point guards and centers, because both can be franchise players. That would never work in the NFL. Nobody would ever claim that the best left guard is worth as much as the best quarterback. That is why the NFL's franchise tag is determined by the value of the highest salaries at each position.

Pro Football Hall of Fame voters are forced to begin the process from an illogical place. They have to spread the votes around the field—and that’s a problem, because they don’t have enough votes. Each class is capped at five players per year (plus senior candidates).

This is why five per class is not enough:

The last 10 players elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame played, on average, 18 major league seasons. NFL players rarely come close to that. Even guys who seemed to play for a long time clock out relatively early. Joe Thomas and Darrelle Revis each played 11 seasons. Ed Reed played 12. Calvin Johnson only played nine seasons. Patrick Willis played eight.

If a football player can build a Hall of Fame case in 10 years, and baseball players build one in 18, then that means that the average football position is producing Hall of Famers at almost twice the rate of the average baseball position. That gap will only increase, because lately, Pro Football Hall of Fame voters have embraced players with high peaks but short careers. Tony Boselli started 90 games. Terrell Davis had four fantastic seasons, got injured, and played 17 more games. I’m not going to debate their candidacies here. But those elections strengthen the case for other players with similar career arcs.

This is all compounded by the fact that football also has more positions than baseball. Every NFL team has 11 starters on offense and 11 on defense, plus ] a kicker, punter and best returner. That means there are 25 positions that should have at least some representation in the Hall of Fame. Not equal representation. Some representation.

Baseball teams have 11 positions that deserve some representation: Nine everyday players (including designated hitter), starting pitcher, and reliever. Now, pitchers obviously don’t pitch in every game, and some teams employ multiple pitchers who are performing at a Hall of Fame level. But football teams still have many more positions that should be represented in the Hall of Fame.

It makes sense for the Baseball Hall to place all players in the same pool. One can reasonably weigh the relative value of a second baseman and a centerfielder. Comparing a left guard to a cornerback is a lot harder—and comparing any quarterback to a non-quarterback is harder still. But the Hall of Fame asks voters to do it anyway.

So rather than simply vote for the most dominant players at each position in each era, Pro Football Hall of Fame voters have to manage the line: One receiver at a time … this guy will obviously get in but we have five ahead of him … oops, we ignored this position entirely for a few years, gotta rectify that …

This is how ridiculous it gets: When Cris Carter retired, he was No. 2 all-time in receptions and receiving touchdowns, third in receiving yards. He was not elected to the Hall of Fame until his sixth year of eligibility. James Lofton retired as the NFL’s all-time leader in receiving yards. When he became eligible for the Hall in 1999, he was not even a finalist. He was elected on his fifth ballot.

There can be sound reasons a Hall of Famer does not get in on the first ballot. Some cases are stronger than others; sometimes voters need time and context to come around. Sometimes the delay is a small punishment for an ethical or moral transgression, but those cases are pretty rare.

Mostly, players wait because the process is built to make people wait.

From 2006 to ‘20, there were 89 finalists. Of those 89, 83 have made the Hall of Fame. Some made it as senior candidates or on special ballots; others waited years until a spot opened up. What is the point of winnowing the list down if almost everybody on it will get elected eventually anyway?

Waits are not even the main problem. They are a symptom of a larger system failure. When obvious Hall of Famers like Strahan and Thurman Thomas have to wait in line, that means that less-obvious-but-still-deserving candidates never even get proper consideration.

Kicker Adam Vinatieri was one of two kickers on the 100th anniversary team, but when he became eligible for the Hall last year, he was not elected. Vinatieri was a finalist, which is more than we can say for former Raiders punter Shane Lechler. Lechler made the 100th anniversary team and two all-decade teams. He was a first-team All-Pro six times. He became eligible for the Hall of Fame in 2023 and has never even been a semifinalist.

In terms of overall value to a team, Vinatieri and Lechler will never be among the five best candidates on a ballot. But Devin Hester wasn’t, either. Hester was elected in 2024—ahead of Antonio Gates, among others—because he was probably the best returner ever.

It is time for the Hall of Fame voting process to reflect the game itself. Like this:

Separate ballots by position group

Let’s make player comparisons reasonable. Group candidates like this: quarterback, offensive line, offensive skill positions, defense and special teams. This way, everybody has a path to the Hall, and Vinatieri does not have to compete against Drew Brees.

Clear-cut finalist guidelines

Advance the following players to finalist: one quarterback, one offensive lineman, two offensive skill players, four defensive players, one special teamer and three other players, regardless of position. That way, Brees and Eli Manning can both advance, or the Hall could finally address its glut of receiver candidates.

No more five-vote limits

Ask voters to vote yea or nay on the finalists. Tell them they are not required to vote for anybody and should only vote for those they think belong. Trust them to take it seriously—because they already do.

Group coaches and contributors together—and remain flexible

Coaches and contributors should be in their own category. Give voters some leeway there, too. That goes for the entire architecture I’ve laid out here—adjust the system as warranted over time. If voters start electing mediocre special teamers, that can be addressed.

Look, it’s just one possible solution. It’s certainly not the only one, and it might not be the best one. But it would make a hell of a lot more sense than what the Hall does now.

More NFL on Sports Illustrated

Michael Rosenberg is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, covering any and all sports. He writes columns, profiles and investigative stories and has covered almost every major sporting event. He joined SI in 2012 after working at the Detroit Free Press for 13 years, eight of them as a columnist. Rosenberg is the author of "War As They Knew It: Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler and America in a Time of Unrest." Several of his stories also have been published in collections of the year's best sportswriting. He is married with three children.

Follow rosenberg_mike