Memories of a hockey hero

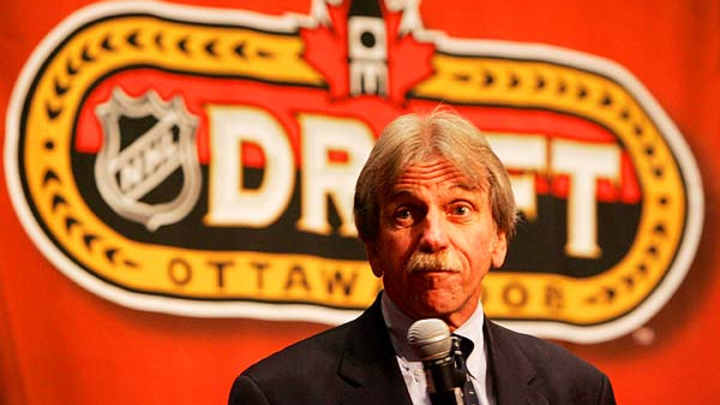

Former coach and NHL scouting director E.J. McGuire was the definition of a true hockey man as well as a tireless innovator who had a major impact on the game he loved. (Bruce Bennett/Getty Images)

By Stu Hackel

E.J. McGuire was a hockey hero. Not the kind of hero who, like Sidney Crosby, Alex Ovechkin, Corey Perry or Jonathan Toews, pulls on a sweater and does magical things such as scoring big goals in packed arenas and triggering wild celebrations. No, E.J. McGuire was the kind of hero who fans don't really see, a guy who quietly dedicates his life and all his considerable talents to create the Crosbys, Ovechkins, Perrys and Toewses you cheer for.

In empty arenas, behind benches, observing from the stands or press boxes and in small offices with computers and video screens, E.J. spent decades probing like a scientist, trying to figure out how to make hockey players and the game itself better. It became his life's mission and he was damn good at it, although he probably would never have put it that way. He just loved being in the game and contributing what he could to a team effort. He did not seek any glory other than the personal satisfaction of a job well done.

E.J. passed away from a vicious form of cancer on Thursday -- as if there is any other kind. He was my friend and he was as smart and well-educated a hockey guy as I've ever known. He could have done anything with his life, but he chose hockey and the game is better because of it.

He was one of those Western New York kids who grows up idolizing the Sabres and playing the game and just loving it all beyond reason. There are lots of kids like that, and some of them -- such as Brian Gionta and Patrick Kane -- even make it as NHL stars. That wasn't E.J.'s fate; he wasn't in that category as a player. (He used to joke that his college coach told him, "You may be small, but you're slow!"). He was a team-first player, and that led him to become captain of the SUNY-Brockport team during in his senior year. His selflessness characterized his entire professional life.

I first met E.J. when he was an assistant coach to Mike Keenan with the mid-'80s Flyers. He had hooked up with Keenan, he later told me, in 1980 while at Brockport. They met at a coaching symposium, and when Keenan was hired by Sabres GM Scotty Bowman to coach the AHL Rochester Americans, E.J. began advising and assisting Keenan (for little or no money at first, as I recall), and then he joined a staff that, in a couple of seasons, would lead the Amerks to the Calder Cup championship. When Keenan was hired by the Flyers, he brought E.J. with him.

I worked in the NHL office at the time, and a coworker who knew E.J. introduced us after a Rangers-Flyers game in New York. E.J.'s weathered complexion and grade-A mustache (almost as good as Lanny McDonald's) made him look a bit like the Marlboro man. Unlike Keenan -- who had quickly gained a reputation as something of a tyrant -- E.J. had a genuine warmth, a joyous sparkle in his eyes and a friendliness that put anyone at ease. In fact, as I came to learn from Flyers TV producer Mike "Finn" Finocchiaro, E.J. was the glue on Keenan's extraordinarily large (for the time) staff, which also included Ted Sator, Paul Holmgren, Bernie Parent, Bill Barber, Pat Croce and Finn himself as the video coordinator. And it was E.J. who played good cop to Keenan's bad cop with the young Flyers players. After any of Keenan's regular dressing room explosions, "E.J. would be the Medic taking care of the wounded," Finn told me.

As editor of the league's magazine GOAL, I was interested in stories on emerging hockey trends and E.J. was on the cutting edge. Hell, he was the cutting edge. He lugged around a huge IBM computer in what looked like a black suitcase. (Finn told me the Flyers' trainers, who had to haul it with the team's gear named it "Serge, the first Russian Flyer.") You'd see E.J. walk though the arena with it after a game at Madison Square Garden and he looked like a salesman from the city's garment district who had mistakenly wandered into the big, round building on Seventh Avenue.

But E.J. would watch games from the press box and enter all sorts of data that no one else was tracking in 1985, including players' ice times. After a game, while every other hockey coach could be expected to be at the bar, chewing over the evening's events, E.J. would distill all that information back in his office and sync it up to video of the game that Finn gave him.

"Roger Neilson had been doing things with video," Finn recalled, "but this was Roger on steroids." They'd stay there until 1 AM -- and if the computer crapped out, which was not infrequent, maybe 3 AM -- and then E.J. would be back at it the next morning to go over the results with Keenan.

Some of what E.J. did with the video was clever: If the Flyers were playing the North Stars, E.J. would get Finn to find tapes of goals they had scored against Minnesota and he'd splice them together and add music, then show them to the team to psyche up the players. And some of it was useful: E.J. would examine the tapes to find each opponent's tendencies, so if he noticed a Capitals player had trouble turning a certain way, he'd tell the Flyers to go around that side.

E.J. never rested in his pursuit of finding new ways to adapt technology to hockey. In Vancouver, he once heard about a video system developed at a university in British Columbia that was used to track ice times of pee-wee players. He drove out of Vancouver to the school with Finn for a demonstration and found it was superior to the way he was doing it for the Flyers. The following season, E.J. had that system in Philadelphia.

Then Keenan learned that he could downlink the satellite backhauls of other teams' games, and he had Finn buy satellite dishes for each coach so they could spy on the entire league. Finn says, E.J. would dedicate every night to watching games at home from all over the league, staying up for the West Coast matches, too.

When Finn showed E.J. how to find the satellite signal that just transmitted the natural sound of the game in the arena without announcers, E.J. would watch that channel and listen to the entire game to see what he could learn from the players talking on the ice. He'd videotape those games and compile them into what he called "a communications tape," revealing how certain verbal cues on the ice led to players' specific actions. (His favorite incident on these communications tapes, Finn says, involved defenseman Kjell Samuelsson who, when passed the puck in his own zone by teammates, found himself facing four opposition forecheckers. The microphones on the glass caught Big Sammy blurting, "Oh great! Now what do I do?")

Assistant coaches do these things regularly now, but I don't think many, if any, were doing them 25 years ago. E.J. set a standard for innovation and dedication that helped change coaching.

Learning about the sophisticated approaches that he was taking -- to E.J., it was all just "neat" stuff, neat being how Upstate New Yorkers described things that Downstaters called "cool" -- I grew impressed with how really brilliant this guy was. I came to learn that he had a Master's degree, which was highly unusual for anyone in hockey, and he planned to get his Ph.D., which he eventually got.

And he could write. When I was assembling the 1988 All-Star magazine, I asked him if he'd like to collaborate with me on a story about Keenan, who was coaching the Wales Conference team. I was collaborating with John Muckler on a profile of Glen Sather for the same issue and had done things like that with a few dozen hockey personalities.

"Would it be O.K. if I tried writing it myself?" E.J. asked. I quickly agreed -- hey, less work for me -- and in a few weeks, he handed me one of the best-written profiles of Keenan anyone has ever composed, perhaps the first that was sympathetic. I didn't change a word.

Looking through some old issues of GOAL, I found a 1987 story that E.J. did with Matt Carlson on faceoff positioning and strategy. In the introduction, Matt wrote that E.J.'s story was based on a seminar on the subject he had taught the previous summer for Level 4 of Canada's National Coaching Certification Program. E.J. was always eager to share what he knew -- and he knew a lot. But he never acted like it. There was no trace of intellectual arrogance or boastfulness about him. I can't imagine he ever thought of lording his education over anyone.

As with almost everyone in the game, the jobs come and go and E.J. parted company with the Flyers after Keenan was fired. The two went to Chicago. His quest for innovation didn't stop with a change of address. I'd run into him at a Blackhawks game and he'd tell me about some "neat" new video or "neat" new computer system he was using. "Everything was 'neat' with E.J." Finn laughs. "Every time I hear the word 'neat,' I think of him."

Eventually E.J. married, had kids, and started moving around a lot after his time in Chicago. Gary Meagher on NHL.com has an excellent story chronicling his career (with lots more on E.J. linked to that piece). He wanted to establish a reputation for himself apart from Keenan and he did. Mostly, it was further out of the spotlight than he was as Keenan's assistant, but that was hardly important. What was important was coaching and teaching players, from the junior ranks up to the NHL.

E.J. truly wanted to be an NHL head coach and, for a few games in the early '90s, he briefly stood in for Rick Bowness (I can't recall why; Bowness might have been sick) in Ottawa during the Senators' first few awful seasons. We got together one night in New York after the Rangers had skunked the Sens and I expected E.J. to be downcast. But he was the same smiling, upbeat, resolute guy he had been while coaching teams that played for championships.

E.J. became something of a coaching nomad after his three years with the Sens, a couple of seasons in the OHL, a couple in the AHL. In 2000, when his friend Shawn Walsh, the heralded coach at the University of Maine, was diagnosed with cancer, E.J. stepped in for two months as a "guest coach" before returning to the Flyers as an assistant under Bill Barber. He joined the NHL's Central Scouting Bureau in 2002. I had expected him to continue coaching. But Finn thinks, "It was the perfect job for him. He loved scouting. He loved kids learning how to play. He loved every phase of hockey. He wasn't an NHL hockey fan, he was a hockey fan."

And, as the stories on NHL.com relate, E.J. brought the same innovative approach to scouting that he did to coaching.

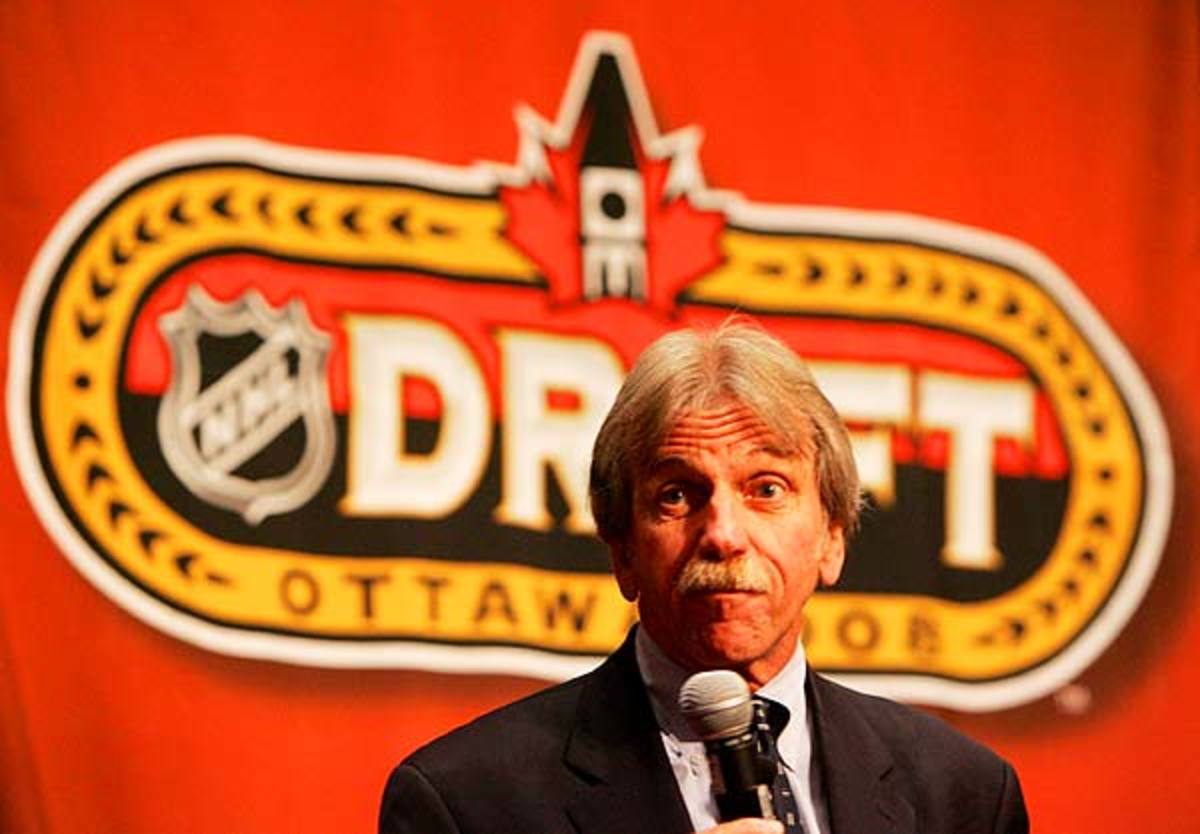

During the lockout, I was working in U.S. junior hockey for the North American Hockey League and when the labor dispute finally ended, I drove from New York to Ottawa for the Entry Draft in August, specifically to seek out E.J. and talk to him about Central Scouting's perception of the NAHL. I just wanted to say hi in person and maybe set up a phone call to discuss things later. I knew it was probably the busiest day of the year for him,but once he saw me, he gave me that big smile under his mustache and we moved to a quiet corner and spent about 15 minutes together, talking business and catching up. I didn't expect it, but in retrospect, I shouldn't have been surprised.

It was Mike Keenan who told me a couple of weeks ago at a sports luncheon that E.J. was going to die. I was shocked, as was everybody. He had hidden his illness from everyone in hockey for a long time and I can't really say why. But shortly after he told his Hockey Operations bosses, Colin Campbell and Mike Murphy, they went to Florida for the GMs meetings and E.J., who was already weakening, came into the office to run the video review room in their absence. A team player 'till the end.

After Keenan gave me the awful news, I got in touch with Finn, who Keenan had also called. We also spoke on the phone after E.J. passed away and consoled each other, two hockey guys mourning another. We swapped some old stories and had some laughs about the old days.

Finn sighed, "There'd be some old former player who had knocked around the game and he might have a summer hockey camp way up in Quebec. He'd get in touch with E.J. and ask him to help him out at his camp. I'd ask 'Do you know this guy?' E.J.'d say, 'I kinda met him when he was coming up in the minors. What am I gonna do? I'll go.' And he'd get in his Camaro, load up his VHS tapes and drive to northern Quebec and give his speech. He'd help anybody if it had to do with hockey."

E.J. McGuire was a neat guy.