Two Minutes for Booking: The Devil and Bobby Hull

Courtesy of Wiley & Sons

By Stu Hackel

If hockey ever produced a cautionary tale, it's the life of Bobby Hull. That tale, and not merely recounting Hull's on-ice exploits, is the approach taken by award-winning Toronto author Gare Joyce in his excellent new book, The Devil and Bobby Hull (John Wiley & Sons, 274 pages).

Hull was hockey's biggest attraction in the waning days of the Original Six era, more charismatic than the laconic Gordie Howe, flashier than the decorous Jean Beliveau. In his day, he was King of the Ice ( to borrow the honorific crown conjured up by the late Paul Quarrington in his great 1988 hockey novel, King Leary). Hull's reign was wedged between those of Rocket Richard and Bobby Orr, although he was hardly in decline during Orr's peak. He was not only the NHL's top goal scorer -- the first NHLer to break the 50-goal barrier in a season -- but also it's most explosive, visible and marketable player.

Five times a Sports Illustrated cover subject -- unprecedented for an NHL player of that time -- Hull's stardom transcended the game, and through his numerous endorsements, which doubled his Black Hawks salary, Gare establishes that he became the first hockey figure to gain continent-wide recognition and was the impetus for the league's first great expansion in 1967.

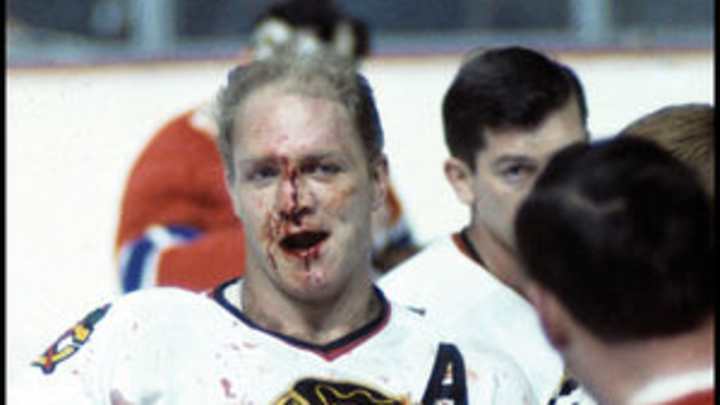

Handsome, muscular and telegenic, Hull's smiling face -- both with and without his false teeth in place -- was the face of hockey when he skated for the Black Hawks (that's how the name was spelled back then, two words) and, in some ways, pro sports. "Hull was the Canadian Superman," Joyce writes. His tiny hometown, Port Anne, a few hours east of Toronto, was Canada's Smallville. What another small town blond strong boy, Mickey Mantle, was for many American kids, Hull was for their Canadian counterparts: the athlete they dreamed they'd grow up to be.

"At the start of the '70s, it was unthinkable that Bobby Hull was going to end up being the player no one wanted to be," Joyce writes. "That he'd go from having it all to having nothing. From pride to shame.

"That's exactly what happened."

With his talent for turning a phrase and ability to tell a story, Joyce chronicles Hull's rise and fall. from hero of Point Anne -- a company town whose citizens believed their employers had their best interests at heart -- to big city superstar, whose employers, the Wirtz family, pinched every penny and deceived their biggest asset.

Like all 120 NHLers of his day, Hull was bound to his club and had little power get true value for his contribution to the bottom line. That contribution came not just in goals, wins and the 1961 Stanley Cup -- the Hawks' only one between 1938 and 2010. He was also the most popular athlete in town, the biggest magnet that attracted the -- wink, wink, Mr. Fire Marshall -- 16,666 fans to each Black Hawks game at Chicago Stadium, with ownership not only banking the take from the turnstiles but also the family-owned parking lots and concessions in and around the building.

When he felt that promises and agreements between him and the club had been broken, Hull's unease with his compensation became known when he temporarily retired after being denied a $100,000 salary at the start of the 1968-69 season, a de facto holdout. It ended with him returning for the $60,000 the Hawks wanted to pay him, a $17,000 fine for time missed, and a public apology. That embarrassment was the beginning of his end in Chicago.

Until then, Hull's image had been sterling, which was standard for athletes of the time. He famously signed every autograph, holding up the team bus for an hour if need be until each scrap of paper had been signed. He gave the most genial and sportsmanlike interviews even after losing Game 7 of the 1965 Stanley Cup Final. There was no common knowledge of his often turbulent, sometimes violent marriage -- in fact, he and Joanne were portrayed as the perfect couple -- his mean behavior after a couple of beers. his arrogance, his stubbornness. If Joyce is rough on the hockey establishment for its treatment of Hull, he is equally critical of the man out of uniform.

The chance for Hull to avenge the Hawks' malevolence and jump to the nascent World Hockey Association for a million dollars changed everything. Joyce traces each step (making a serious contribution to hockey history in his recounting of the WHA's legal challenge to the NHL's reserve clause). He pulls no punches in suspecting the Wirtz family of having mob ties, and repeats the saga previously told in WHA histories that only in Chicago did a judge rule against a lawsuit involving the WHA. Of course, original Winnipeg Jets owner Ben Hatskin rouses the same suspicions in Joyce's recounting of the rebel league's founding.

But Joyce sees Hull's run to freedom and fortune in the WHA as not unlike the film The Devil and Daniel Webster, in which a luckless farmer makes a Faustian bargain for prosperity in exchange for his soul, "an allegorical lesson on greed as seduction against better judgment."

Hull would once again pay a price for his independence, first by being prevented from joining Team Canada in the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet national team. The lost opportunity of the game's biggest player being denied a chance to shine on its biggest world-wide stage haunts many to this day -- but not Hull, at least not in his conversation with Joyce, which is sprinkled throughout the book in italicized print.

Hull comes off vague about his feelings on the Summit Series as he sits in Wayne Gretzky's restaurant in Toronto last year while promoting The Golden Jet, a pictorial history of his Chicago days. We reviewed that book here last year. If Hull's reflections and opinions are sometimes less than illuminating, which isn't always the case, they provide a necessary framing for his story.

The Winnipeg years, of course, had their ups and downs, as did the WHA, but Hull's partnership with Ulf Nilsson and Anders Hedberg resulted in a few league championships and some of the most breathtaking hockey ever played. Joyce properly places the on-ice and off-ice results of Hull's jump in perspective, noting that his defection bettered the lot of every pro hockey player from that point onward, and the Jets' North American-Euro hybrid style presaged the great Oilers dynasty of Gretzky's day and the current NHL flavor.

For all Hull accomplished, however, he did become an outcast for most of his post-playing career. Some of that was no doubt his own doing, the consequences of his own often-irritable behavior. And some of it was the hockey establishment holding a grudge and turning its back on him. Joyce points out that other greats who followed, like Gretzky and Mario Lemieux, found places in the NHL after they finally hung up their skates. Hull was left to raise cattle and sell bull semen. He was kept on the outside until Bill Wirtz died in 2008 and his son Rocky repatriated Hull by making him at least an ambassador for the Blackhawks.

But Hull never had a job where was an integral part of an NHL team, one where he'd be making hockey decisions. He never became a Beliveau or Steve Yzerman, which Joyce believes he should have been.

Worse was the public disintegration of his marriage, and Joyce unsparingly reviews the sometimes bizarre, sometimes frightening and largely painful relationship between Bobby and Joanne -- as well as their children (although Brett's role in Joyce's narrative is far smaller than some of his siblings) -- with some strong insight, including the fact the Hull himself had been an abused child. When his marriage finally split, Hull was lost, Joyce writes. He may have been cruel and disloyal to his wife, but he also depended on her.

Some of the directions Joyce takes in discussing Hull's personal life go a bit further than warranted by the evidence he presents. For example, he wonders if Hull's occasional forgetfulness is evidence of CTE, the degenerative brain disease that can be triggered by multiple concussions. Considering Hull's age (he was 71 at the time of their meeting) and the hard-drinking lifestyle he's led, there can be any number of explanations for his behavior.

But the fine writing and strong sense of narrative prevail over any shortcomings, making this not just an exceptional hockey book, but an exceptional one.

"When Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux and other great players emerged after Hull's fall from grace, they knew his story," Joyce writes. "They knew that fans perceived him, fairly or not, as a talent, but not a winner. They knew he was punished for his hubris, never forgiven for taking on the Black Hawks' owners and the National Hockey League. They knew his private life had become public scandal. They know his commercial image had been exposed as a fraud...

"Others who came after him went to school on Hull's experiences. No giving in to inner demons. No giving in to temptation. No deals with the Devil. No one wanted to fall like he did, from fairy tale to cautionary tale."