Racism denied Herb Carnegie but didn't stop him

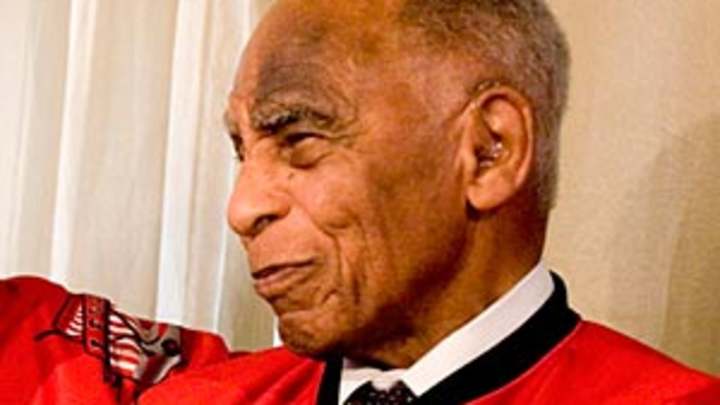

Though he never played in the NHL, Herb Carnegie inspired such all-time greats as Frank Mahovlich and Jean Beliveau. (Darren Calabrese/AP)

By Stu Hackel

Herb Carnegie passed away on Friday, a great hockey player who deserved a shot in the NHL. It was denied him because he was black. But while the institutional racism of all big league pro sports, including the NHL, in that era prevented him from reaching his goal, he spent his post-playing years mentoring youngsters and started one of the first hockey schools in Canada and a foundation.

As an 18-year-old, Carnegie began attracting attention in 1938 while playing for the Toronto Junior Rangers under coach Ed Wildey, and one who saw him play at Maple Leaf Gardens was Conn Smythe, the owner of the Maple Leafs. Wildey told Carnegie that Smythe would sign him the next day...if he were white. Later, Smythe was widely reported to also have said, "I'll give any man $10,000 who can turn Herb Carnegie white." It was a slight that upset Carnegie at the time.

"The Toronto Maple Leafs was the team I rooted for as a boy," Carnegie said in a 2002 interview. "And to find out that was how the owner of the team I rooted for felt about me was shattering, just shattering."

It still upset him decades later, as Elliotte Friedman found out when he profiled Carnegie over the CBC on the Hockey Night in Canada pregame show.

Carnegie became a star in the mining leagues of the 1940s, small semi-pro loops that played the mining towns of northern Quebec and Ontario. That's where Hockey Hall of Famer Frank Mahovlich, who grew up in Timmons, Ontario, saw him play. Mahovlich said Carnegie's slick moves and passing excellence inspired him, and the man who would later be called The Big M wanted to emulate him. Mahovlich told author Cecil Harris in Breaking The Ice, that he expected he'd soon see Carnegie and many other black players in the NHL. But that never happened.

The closest Carnegie came was a tryout given to him by the New York Rangers at their 1948 training camp. Carnegie was playing in the senior Quebec Provincial League for the Sherbrook Randies by that time, on a very productive line with his brother Ossie and Manny McIntyre, an all-black line dubbed, among other things, "The Black Aces." He'd won a scoring title, two consecutive MVP awards, and led Sherbrook to the league championship when the Rangers letter arrived.

"They were a good enough line to play in the American League, which was a level below the NHL," Hall of Fame referee Red Storey, who also played junior hockey with Carnegie, told Harris. "But Herbie was the leader. They couldn't have gone anywhere without Herb. He was good enough to play in the NHL. It was strictly color, not talent, that kept him out."

After a few days with the Rangers, it was obvious he belonged in pro hockey. The Rangers wouldn't offer him an NHL deal, however. They would give him $2,700 to play for their lowest level minor league team in Tacoma, Washington. Carnegie declined. He was already making $5,100 playing for Sherbrook and supplementing that with outside work in Quebec. The next day, the Rangers upped their offer to $4,700 and a place on their St. Paul USHL team, a step up on the ladder. He turned that down as well.

After a week of training camp, Carnegie was offered $4,700 and a place on the Rangers' top farm team, the New Haven Ramblers. With a wife and three children to support, he wouldn't take the pay cut, but he asked the organization if he could remain in camp, which he did, playing against NHLers, until the Rangers left upstate New York to begin their preseason barnstorming schedule. That was the last time an NHL team called him.

Some believe that Carnegie should have taken the Rangers' last offer and done some minor league apprenticing, as Jackie Robinson had done playing a season for the Montreal Royals before the Brooklyn Dodgers called him to the major leagues. In New Haven, Carnegie would have been two hours away from Madison Square Garden.

And it might not have taken long to make the NHL, some believe. Just prior to the start of the season, a car accident injured four Rangers players, including their top centers Buddy O'Connor and Edgar Laprade. O'Conner suffered broken ribs and was out for six weeks while Laprade had a concussion (which meant little back then; he kept playing after the accident and his production declined that season from 47 to 30 points). If Carnegie had signed with the organization, he might well have been summoned to fill in for O'Connor.

"Don't you think the Rangers would have called me back if they had been serious about wanting me?" Carnegie told Harris. But he believes they wanted nothing more to do with them after their last contract discussion. They had told him that if he signed with the Rangers and went to New Haven, he'd make international headlines. "I told them my family couldn't eat headlines. That was probably when the Rangers decided to forget about me."

Herbie went back to Sherbrook and won a third straight MVP title instead. He later jumped to the Quebec Aces where he became a teammate and mentor for Jean Beliveau for two seasons in the Quebec Major Hockey League. "Herbie was a super hockey player with a beautiful style, a great playmaker," Beliveau told Harris. "In those days, the younger ones learned from the older ones. I learned from Herbie."

Obviously Carnegie was a good teacher.

Beliveau had seen the Black Aces play as a youngster, when Sherbrook visited his hometown Victoriaville Tigres. "It is my belief that Herbie Carnegie was excluded from the National Hockey League because of his colour," Beliveau wrote in the introduction to Carnegie's autobiography A Fly In A Pail Of Milk. "How could NHL scouts overlook not one, but three Most Valuable Player awards for a player on a team in a top senior league?"

He retired from playing shortly after Beliveau signed with the Canadiens to begin his magnificent career. Bitter that he had not gotten his chance, he channeled his anger constructively, starting the Future Aces hockey school, part of which involved teaching young players the values of cooperation, teamwork, attitude and sportsmanship. It grew into a foundation in the 1980s that helped raise scholarship money for deserving students. He helped countless kids along the way. He was given the Order of Canada, the Order of Ontario and an honorary doctorate by York University. An elementary school and a community center were named in his honor.

Carnegie was also a senior golf champion during the 1970s.

Harris called Carnegie “the best black player never to reach the NHL.” Instead of being the sport's Jackie Robinson -- that honor went to Willie O'Ree -- Harris thinks of Carnegie as “the Josh Gibson of hockey,” Gibson being the great power hitting catcher of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays in the Negro League who never got to play in the majors. That comparison is true to an extent, although Gibson died young from a brain tumor and was angry at the racism that denied him his shot at the big leagues. A hockey guy to the end, Herb Carnegie checked his anger and spent the rest of his life working to impart a positive attitude in young people. That sort of inspiration won't die.

COMMENTING GUIDELINES: We encourage engaging, diverse and meaningful commentary and hope you will join the discussion. We also encourage, but do not require, that you use your real name. Please keep comments on-topic and relevant to the original post. To foster healthy discussion, we will review all comments BEFORE they are posted. We expect a basic level of civility toward each other and the subjects of this blog. Disagreements are fine, but mutual respect is a must. Comments will not be approved if they contain profanity (including the use of punctuation marks instead of letters); any abusive language or personal attacks including insults, name-calling, threats, harassment, libel and slander; hateful, racist, sexist, religious or ethnically offensive language; or efforts to promote commercial products or solicitations of any kind, including links that drive traffic to your own website. Flagrant or repeat offenders run the risk of being banned from commenting.