For U.S. Speedskating, Olympic failure is about more than the suit

SOCHI, Russia -- The way U.S. Speedskating has bungled these Olympics, its motto should be: “Does this suit make me faster, higher, stronger or not, because I’m just so confused and HELP ME HELP ME WAIT DID THE GUN JUST GO OFF?”

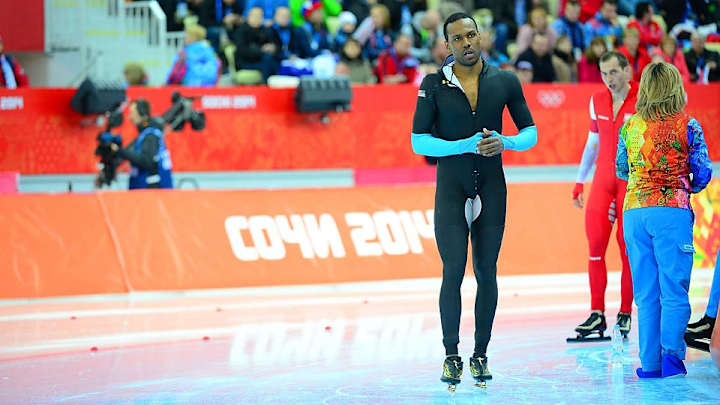

What a debacle. Skater Brian Hansen admitted that “statistically,” it’s indisputable: There is something wrong with the entire team. This was supposed to be one of the best U.S. speed-skating teams ever. Instead, nobody has medaled. Nobody has come particularly close to medaling. It’s like the Americans forgot to bring their thighs.

Failure is at least as interesting success, so let’s take a moment to examine why the American speed-skating team has failed. The simple story, which has been written and discussed, is that Under Armour’s new speed-skating suits, which are supposed to reduce drag, have slowed down the skaters. That story is compelling -- it smells like a money grab, and it gives us all a chance to rip into a big, evil apparel company. But I don’t think the suits are the problem.

There are several reasons for this debacle, and piled on top of each other, they lead to comments like this, from American star Shani Davis:

“The energy was really bad. There were just so many things going on: ‘What’s going on with this? What’s going on with that? What’s going to happen here?’ … If I could have just put that energy into performing and skating, it would have been a totally different outcome.”

Says U.S. Speedskating executive director Ted Morris: “I see where he is coming from, from the perspective that we’ve all been scratching our heads. It’s a tough situation. It isn’t any different than the Denver Broncos in the second half of the Super Bowl. They’re stunned.”

Morris has only been on the job five months. He emphasized that he is trying not to look back, and will do a full evaluation after the Olympics.

Me? I’m looking back, and I’m evaluating now.

What has gone wrong?

1. The suits:

The problem is not the suits themselves. Under Armour worked with Lockheed Martin on creating the most aerodynamic suits, and they have designed speed-skating suits before. When Shani Davis and his teammates in the men’s 1,500 voted unanimously to switch back to their old suits Saturday, they did so knowing that the old suits were also made by Under Armour.

The problem is timing. But Morris says a decision was made to “provide the athletes with an advantage as close to the Olympics as possible.” That means the skaters got the new suits for the Olympics, not before. Morris, a former swimmer, compares it to shaving before a big event. The idea was that the new suits would make the skaters go just a little faster, and that would give them an extra mental boost.

It backfired. The decision-makers failed to consider that speed-skaters need to feel comfortable in their suits. They don’t want to think about whether they have the best equipment – they want to know it. This was like asking a baseball player to try a new bat and glove for the World Series.

“If you look at World Cup races, you go through your World Cup, you skate, you perform,” Davis said. “You’re not thinking about what’s slow or what’s fast. You go to the line and skate the best you can.”

2. The wrong ice:

Blaming the ice for a bad skating performance is akin to a cook blaming his lousy meal on his pots. Still, this is another case of the U.S. trying to create a perfect situation for its athletes, only to watch it backfire. Many Americans train on some of the fastest ice in the world in Salt Lake City. The ice here is considered more like “worker ice” – softer.

Everybody is skating on the same ice. But it is a bigger adjustment for the Americans than for most people.

3. The U.S. team was probably overrated:

Morris said that a few months ago, executives were hopeful for six medals, total, from long-track and short-track. A wildly successful season changed expectations. In retrospect, it is possible that other teams were trying to peak for the Olympics, and so the Americans’ World Cup success was probably misleading.

“We’re beating the people we thought we had to beat,” Morris said. “We’re skating faster than those people. Other people have blown by the rest of the field.”

When you enter an Olympics expecting a bunch of medals, and you fail in a few early races, you fall victim to …

4. Momentum:

Add factors 1, 2 and 3 to a lousy start, and all of a sudden doubt creeps into athletes’ minds. This team is thinking about too many things besides winning races. The four Americans in the men’s 1,500 Saturday voted to go back to the Under Armour suits they used all year in the World Cup. Predictably, that didn’t work, either. Hansen, the top American finisher, was 7th. Davis, who hoped to medal, finished 11th.

Davis said the vote was “unanimous” to go back to the old suits. And that sounds like the athletes are blaming their suits for their poor performances. Don’t think of it that way. The issue is not the suits; it was the timing. Davis didn’t know the suits might have been flawed until a Dutch reporter told him. Davis told the U.S. Speedskating staff.

“And then,” Davis says, “things started happening.”

By Friday night, officials were working frantically to make sure the World Cup suits were approved for Saturday’s competition. Davis said he was “restless,” and he tried desperately to take responsibility for his performance, but he was also honest. His poor performance in the 1,000 got into his head and slept there. Davis is not alone. The entire team does not seem to be in the best mental place to compete against the best in the world, and when that many athletes come down with the same mental affliction, you have to look beyond them.

Now, imagine that each of those factors is worth a fraction of a second. That’s it. That’s all it takes. That’s enough to keep the Americans off the podium.

There has been speculation that the Americans are fading because they trained at altitude and are skating close to sea level. Skating at altitude can artificially lower times. But Americans have done that before with better results.

You can wonder about team chemistry, since the Americans don’t all train together like some other top teams do. But that is not a new phenomenon for the U.S., and as Morris points out, “The Dutch don’t train together. They are all on six different pro teams.”

The Dutch, of course, are enjoying the speed-skating venue immensely. The Americans are … not.

One reason we love the Olympics is that we don’t see them all the time. Athletes get one chance every four years, and they have to seize it. This is what happens when they don’t.

Michael Rosenberg is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, covering any and all sports. He writes columns, profiles and investigative stories and has covered almost every major sporting event. He joined SI in 2012 after working at the Detroit Free Press for 13 years, eight of them as a columnist. Rosenberg is the author of "War As They Knew It: Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler and America in a Time of Unrest." Several of his stories also have been published in collections of the year's best sportswriting. He is married with three children.

Follow rosenberg_mike