O'Bannon v. NCAA, day one: Ed O'Bannon testifies; economist Roger Noll takes the stand

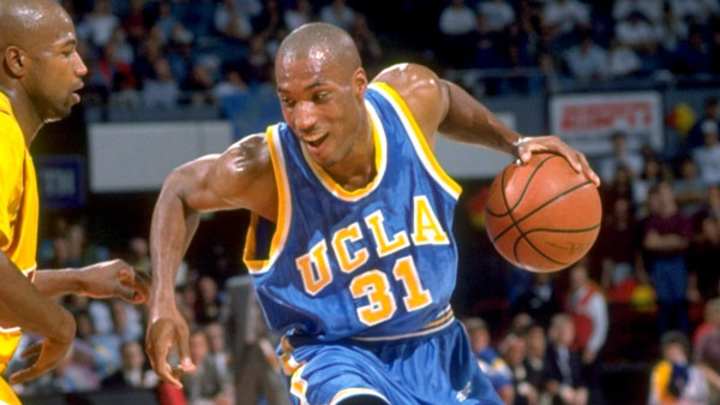

Ed O'Bannon (31), pictured here in 1995, testified about his recruitment on Monday morning. (Richard Mackson/SI)

OAKLAND, Calif. -- On day one of the long-awaited Ed O’Bannon v. NCAA trial, the plaintiffs called O’Bannon to the stand as their first witness.

Plaintiffs’ attorney Michael Hausfeld questioned O’Bannon for approximately 50 minutes. Most questions pertained either to his recruitment to UCLA, with Hausfeld insinuating that O’Bannon was recruited for his basketball talents and not for academic abilities, or to his in-season basketball practice and travel obligations, with Hausfeld suggesting that they interfered with academics. O’Bannon said he would spend 40 to 45 hours a week on basketball, but only about 12 on academics. “I was there to play basketball," he said. "Schoolwork wasn’t much of a priority for me."

Hausfeld’s line of questioning struck at one of the NCAA’s core arguments, which is that retaining the current compensation model is necessary to preserve the integration of academics and athletics.

On cross-examination, NCAA attorney Glenn Pomerantz established that O’Bannon enjoyed his experience at UCLA and remains connected to the program. O’Bannon agreed that perks like visiting the White House after his 1995 championship season were among the benefits he received as a member of the Bruins. The NCAA contends it does not control use of athletes’ images after college. Pomerantz noted that O’Bannon entered into licensing deals (such as an endorsement deal with Nike) shortly after leaving campus and that the NCAA did not stop him. He suggested that O’Bannon could have called EA Sports himself and demanded permission to use his likeness.

Pomerantz also raised several inconsistencies from O’Bannon’s 2011 deposition, in which O’Bannon said he was not interested in representing current student-athletes and that athletes shouldn’t be paid while in college. “With the amount of money they should be bringing in, I think they should be compensated,” said O’Bannon, who was excused after about 90 minutes of questioning.

The plaintiffs next called Dr. Roger Noll, a professor of economics at Stanford and the plaintiffs’ primary expert witness on the antitrust aspect of this case. Noll pulled no punches in declaring the NCAA “a cartel that creates a price-fixing scheme among its members” by imposing limits on athlete compensation.

With prodding from Hausfeld, Noll described the two markets in which he believes the NCAA engages in anti-competitive behavior: the higher education market, in which schools compete against each other in recruiting prospective student-athletes, and the collegiate licensing market for products using athletes’ images.

Noll contends that NCAA members conspire to fix the price for players’ names, images and likenesses at zero. He testified that the NCAA engages in cartel-like behavior by restricting competition, primarily due to the fact that schools cannot be NCAA members unless they agree to abide by the alleged price fixing.

Hausfeld asked Noll to demonstrate how he determined that there is a market for players’ likenesses. He cited a chart showing that 75 percent of schools with a quarterback featured on last season's Davey O’Brien Award watch list sold jerseys with that player’s number. “It’s an indication of value of a product with the individual’s likeness,” Noll said.

Noll also said limits on player compensation cause “inefficient substitutions,” such as revenue spent on facilities to impress recruits rather than directly on recruits themselves. Wilken wasn’t buying it. “Who is harmed by these inefficiencies?” she asked. “Clearly, it’s not the coaches.” Noll could not pinpoint a specific party.

After more than two hours of direct questioning, court broke for the day. Noll’s testimony will continue on Tuesday morning.

For more analysis of O’Bannon v. NCAA, check out SI.com’s complete coverage hub.

Senior Writer, Sports Illustrated Stewart Mandel first caught the college football bug as a sophomore at Northwestern University in 1995. "The thrill of that '95 Rose Bowl season energized the entire campus, and I quickly became aware of how the national media covered that story," he says. "I knew right then that I wanted to be one of those people, covering those types of stories." Mandel joined SI.com (formerly CNNSI.com) in 1999. A senior writer for the website, his coverage areas include the national college football beat and college basketball. He also contributes features to Sports Illustrated. "College football is my favorite sport to cover," says Mandel. "The stakes are so high week in and week out, and the level of emotion it elicits from both the fans and the participants is unrivaled." Mandel's most popular features on SI.com include his College Football Mailbag and College Football Overtime. He has covered 14 BCS national championship games and eight Final Fours. Mandel's first book, Bowls, Polls and Tattered Souls: Tackling the Chaos and Controversy That Reign Over College Football, was published in 2007. In 2008 he took first place (enterprise category) and second place (game story) in the Football Writers Association of America's annual writing contest. He also placed first in the 2005 contest (columns). Mandel says covering George Mason's run to the Final Four was the most enjoyable story of his SI tenure. "It was thrilling to be courtside for the historic Elite Eight upset of UConn," Mandel says. "Being inside the locker room and around the team during that time allowed me to get to know the coaches and players behind that captivating story." Before SI.com Mandel worked at ESPN the Magazine, ABC Sports Online and The Cincinnati Enquirer. He graduated from Northwestern University in 1998 with a B.S. in journalism. A Cincinnati native, Mandel and his wife, Emily, live in Santa Clara, Calif.