Book excerpt: Perry Wallace's story as the SEC's first black basketball player

From Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South, by Andrew Maraniss.Copyright Vanderbilt University Press, © Andrew Maraniss, 2014.

A Long, Hellish Trauma

In December 1966, just four years removed from the riots that accompanied James Meredith’s desegregation of the university, Ole Miss canceled both of its freshman basketball team’s upcoming games against Vanderbilt rather than play against a Commodore team featuring the first two black freshmen in the SEC. The Rebels denied that was the reason for the sudden discovery of two “schedule conflicts,” but nobody outside Mississippi believed them. When Vanderbilt made the trip to Oxford the next season, with the league’s first African American, Perry Wallace, on the varsity roster, it marked the first time a black basketball player had ever played against the Rebels. Wallace describes the night as a “long, hellish trauma.”

Back in high school, when he was taking the first flights of his life and enjoying the attention lavished upon him by college recruiters, Perry Wallace experienced the unlikeliest of conversations while walking down the aisle of one particular plane.

A middle-aged man recognized him and struck up a conversation. The man, it turned out, was a former high school sports star from Jackson, Tennessee. He had gone on to great success in college, becoming the finest all-around athlete in the history of his school, starring in baseball, basketball, and football (and even running a little track), earning all-conference honors as a centerfielder and leading his football team to two conference titles as a running back and defensive back. In one game, he dazzled the crowd by scoring four touchdowns in just about every way possible -- one rushing, two receiving, and one by interception -- and not surprisingly, he had been drafted by the NFL’s New York Giants. An injury cut short his professional football career, and now he was back at his alma mater, coaching the basketball team. When he spotted Wallace walking down the aisle, he introduced himself and casually asked the Pearl High School star whether he would be interested in coming down to play for him.

The man was Eddie Crawford from Ole Miss.

Two years later, in February 1968, as the sophomore Wallace boarded Vanderbilt’s charter flight to Mississippi, the idea of playing a single game in Oxford, let alone an entire career there, was fraught with a sense of danger unlike anything he had ever experienced. Going back to his childhood days in Nashville, when he walked to the Hadley Park library to read about southern lynchings, Wallace had learned too much about Mississippi -- and had experienced some of what the Magnolia State had to offer in a freshman game at Mississippi State a year earlier -- to believe that he was headed south for anything remotely resembling a simple game of basketball. If his worst nightmare was going to come true, this is where it would happen. Oxford, Mississippi, was where he’d be shot and killed.

As the Commodore players unpacked their bags at Oxford’s Holiday Inn and prepared for dinner in the hotel’s El Centro restaurant, tensions were rising on the Ole Miss campus. Earlier in the week, five of the eight varsity cheerleaders had resigned, exacerbating the fact that “Ole Miss school spirit has one foot in the grave already,” according to one student journalist; as the Vanderbilt game approached, “anything to put some life and zing in our spirit” was desperately needed. And while the Commodore players dined, the second act of a drug bust was in motion, with seven Ole Miss students arrested for marijuana possession after three had been busted the night before, culminating a thirty-day investigation. All told, an unusual discontent pervaded the campus in the chill of early February. It was as if the Vanderbilt contingent were the first unwitting guests to arrive at a dinner party where the hosts had stopped arguing just in time to open the door. Whether they were in for any hospitality was another matter.

Commodore student manager Paul Wilson doubted it. Having grown up in Jackson, Mississippi -- attending a segregated Murrah High School that sent dozens of students to Ole Miss every year -- Wilson was the rare member of the Vanderbilt entourage who seemed to understand what Wallace was about to endure, and unbeknownst to Wallace, he took two steps to try to protect him.

First, in creating the travel itinerary for the trip, he assigned himself to be Wallace’s roommate at the Holiday Inn. When Wallace joined the Black and Gold, Wilson said his concern for the plight of blacks evolved from a “struggle they were going through, to one we were going through. He was our teammate.” When the Commodores arrived at the hotel after driving in from the airport, Wilson was surprised to see a number of police cars parked out front: “I remembered the Meredith riots, so I had a real tense feeling. It had to be one hundred times worse for Perry.”

Whatever apprehensions Wilson had about the long night ahead, he was more concerned about the treatment Wallace would receive the following evening from Ole Miss partisans at the Coliseum. Whereas at a basketball school like Kentucky, the fans respected the game and were mainly concerned about the fortunes of their own players, Wilson knew the atmosphere at Ole Miss had traditionally been just the opposite. It had only been in the five years since Crawford’s arrival that seemingly any emphasis had been placed on basketball at all. The Rebel basketball team had a reputation as the place where beefy football players banged around all winter to stay in shape for the gridiron. Before the eighty-five-hundred-seat Coliseum opened in 1966, the team played in the tiny Old Gym (capacity twenty-four hundred), where the fans’ disinterest in basketball was exceeded only by their willingness to scrap. Former Vanderbilt star Clyde Lee recalled a game in 1965 when a teammate caught one of the basketball-playing footballers with an elbow, knocking the Rebel to the ground. Within seconds, a sea of Ole Miss football players, clad in letterman jackets, came pouring out onto the court to take up for their comrade, who had gotten up to retaliate. “Security ran out and circled us in the jump circle at center court until they got everybody settled down,” Lee said. “The security guards stayed close to us for the rest of the game. It was intimidating for us; we were a little worried. Put that into context with the animosity toward Perry and his color, and I can’t imagine.”

Whether it was his idea or that of Steven Ammann, an elementary and high school pal enrolled as a junior at Ole Miss, has been forgotten over the ensuing decades, but Wilson’s second perceptive act was to help create a buffer zone around the Commodore bench. In the days leading up to the game, Wilson got in touch with Ammann, who as a kid who had moved to Mississippi with his family from the Cincinnati area and who had more open-minded views on race than many of his peers. As a fourth and fifth grader, Ammann had taken grief from his new friends in Jackson over his choice of favorite football player, the outspoken Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns. The plan hatched by the two old friends called for Ammann to assemble a group of like-minded Ole Miss students and snatch up tickets in the row immediately behind the Vanderbilt bench. “It was one of those little things that one person can do to try to make things better,” recalled Wilson. More than forty years later, Ammann recalled that his overriding concern was that Wallace not be harassed by hecklers. He and a group of friends walked over from the Lester dormitory to the Coliseum well before game time and took their positions. “I had a great deal of respect for what Perry Wallace was doing,” Ammann said, “so our hope was to create a little distance, to put some people there who would be close to the scene and would not be verbally abusive. There’s something inside of you at a moment like that that says, ‘This should go right for this person.’”

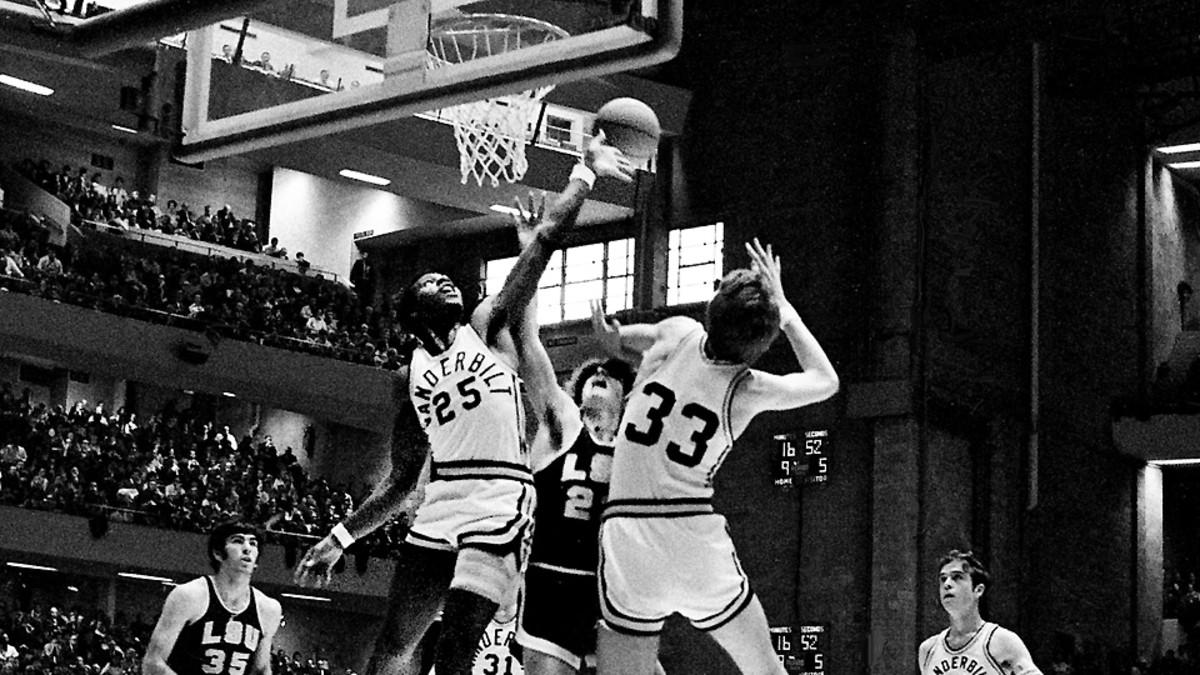

Almost to a man, Wallace and his teammates can recall the scene in Oxford when Wallace came running out on the court for the first time, white socks pulled up high, short black shorts and black jersey, VANDERBILT etched out in white and gold letters in a horseshoe shape above his number 25.

The jeers and the cursing started the moment Wallace emerged from the tunnel that connected the locker room area to the playing court, louder, more sustained, and uglier than any of the Commodores had heard all season. But there was something different about the Ole Miss brand of abuse. Steve Martin, the Tulane baseball player who was the SEC’s first African American athlete in any sport (during Tulane’s final season in the league the previous spring) had experienced some of this when he dug into the batter’s box for the first time in Oxford, and the crowd spelled out N-I-G-G-E-R in a boisterous, preorchestrated fashion. Here on the basketball court, the effect was similar: the words themselves were ugly, but they were made far uglier by the blithe enthusiasm with which they were delivered. For the next two hours, Wallace would serve as this crowd’s entertainment.

As Wallace and his teammates ran through their layup line and shot jumpers while the clock ticked down toward tip-off, Commodore senior Bob Warren noticed something he had never heard before in warm-ups: laughter. Every time Wallace missed a shot, fumbled a rebound, or made even the slightest misstep, the Ole Miss fans near courtside exploded in delight. Every time Wallace made a shot, the crowd booed. And in between, it was, Go, home, nigger! We’re gonna kill you, nigger! We’ll lynch you, boy! Forty years later, Warren was still shaken by the memory. “Those warm-ups,” he said, “were really bad.” Teammate Bob Bundy stopped shooting long enough to look into the crowd to see who was doing the yelling, and by the size and appearance of the hecklers, assumed the ringleaders were Rebel football players, a squad described in the Ole Miss yearbook as a “well-bred” bunch far more refined than the “redneck meats” at other conference schools. Wallace heard the laughter and the threats, “the usual stuff,” he recalled, and he heard another taunt that would remain with him for decades. “There was this group of guys harassing me in warm-ups, and one of them made his voice into what he thought was a black woman’s voice, and he said: ‘I’m from Jackson State. Do you want to come over and [be with] me?’ It was just ugly.” The game hadn’t even started yet, and already things were out of control. And perhaps worst of all for Wallace, he knew he would begin the game on the bench. He’d just have to sit there and wait for the inevitable: when head coach Roy Skinner turned to him and summoned him into the game, the fans would be ready, and the barrage would begin anew.

Tip-off came as scheduled at 7:30 p.m., temperatures outside the Coliseum dipping to near freezing. Ammann and his friends settled into their seats behind the Vanderbilt bench, their plan to protect Wallace from the vilest elements of the crowd already an apparent failure. Commodore fans from Nashville were scattered in pockets around the gym; tickets had been easier to come by than they had even imagined. In all, 3,318 fans showed up to watch, the crowd packed in close to the court, with the yellow-seated upper sections and red middle sections virtually empty. Wallace watched from the bench as the teams traded baskets, the underdog Rebels sticking close to favored Vanderbilt throughout the early going.

Finally, Wallace entered the game for the first time, greeted by the “high-pitched yip, yip, yip of the Rebel yell,” according to journalist Scott Stroud. Immediately, the catcalls grew louder. “I checked into the game and they raised holy hell,” Wallace recalled. “Every time I made a mistake, everybody clapped, everybody laughed.” With just over nine minutes remaining in the first half, Wallace scored his first and only basket of the half, tying the score at 19. On both ends of the court, Wallace and his teammates felt that he was being bumped and bruised more than usual, enduring a physical style of play that referees Ralph Stout and Joe Long overlooked.

Then it happened, a blow that came so fast no one knows who threw the elbow. Fighting for a rebound, Wallace was struck underneath the left eye by an Ole Miss bruiser, knocked so hard in the head that he momentarily lost his vision and staggered to regain his footing. Neither Stout nor Long whistled a foul, nor did they call a halt to the game to allow Wallace to be treated. On the Commodore bench, Bill LaFevor was startled by the Ole Miss cheers, the crowd rising to its feet in delight. Wallace felt “fuzzy,” but no matter how bad he was hurt, the one thing he was not going to do was leave the court. But as he regained his sight, he looked down and saw blood. At the next dead ball, trainer Joe Worden came off the bench to check on Wallace and saw his eye swelling shut. He summoned manager Wilson, asking him to help Wallace back to the locker room. As Wilson grabbed Wallace’s arm and handed him an ice pack, the Mississippian heard the crowd still cheering, still laughing, still cursing “nigger,” a father and son spitting in their direction, one fan yelling, “We’re going to kill you,” and forty years later Wilson said that at that moment, his body was shaking, he was seething, never so angry and embarrassed in his entire life, then or since. Not quite sure what to say to Wallace as they approached the tunnel to the locker room, he simply said, “I’m sorry, Perry.” Wallace, head held high in pride and to stunt the bleeding, kept on walking, looking straight ahead. “It’s OK,” he said.

The halftime buzzer sounded, Vanderbilt leading 41–35, and soon the rest of the team filed into the locker room. Worden checked on Wallace, but the minutes ran by quickly, and Wallace was left on the training table with a bag of ice as coaches, teammates, and managers returned to the court before the second half began. Eye swollen and hands cold from the ice, Wallace was shaken not just by the physical blow but by the relentless taunting, nineteen years old and black and alone in a Mississippi theater of the absurd. He could hear the Ole Miss crowd react when his teammates returned to the court without him: Did the nigger go home? Where’s the nigger? Did he quit?

Despite their awareness of the abuse their teammate had endured during warm-ups and the first half of the game, not one member of the Vanderbilt traveling party stayed behind to accompany Wallace back onto the court. As he walked toward the tunnel to return to the bench for the second half, Wallace understood more clearly than ever that his journey as a pioneer was one that he would be making alone. He asked himself, “Who’s on my side?” and came to the conclusion that the only person he could rely on was himself. Speaking to Vanderbilt Chancellor Alexander Heard a few months later, he described what came next: “Now, I don’t expect you to attach much significance to merely having to run out on a basketball floor, but what I remember most in my life is standing at that huge doorway with that crowd waiting on me with my teammates completely at the opposite end of the floor,” he said, according to a transcript of his remarks. “What would have merely been an occurrence of no consequence for a white player was transformed into a nightmare and a long, hellish trauma for me.”

As Wallace emerged from the tunnel, a group of Vanderbilt fans were the first to see him, and they stood and cheered. Their cheers were soon drowned out by boos.

Steven Ammann said he felt in his heart that a night like this “should go right” for a person in Wallace’s situation, and perhaps Coach Skinner felt a similar calling as the second half approached. Though he kept Wallace on the bench to begin the game and though Wallace was now injured, Skinner made the unusual move of putting Wallace in the starting lineup to begin the second half. In the Hollywood rendition of what would happen next, Wallace would rise above the madness of the crowd, not give a damn about whether somebody wanted to shoot him, soar above the floor for every rebound, shake off another hard blow to the head, score one basket after another, and lead Vanderbilt to a convincing victory.

In real life, yes, he did all that, and he also unleashed a perfect, left-handed behind-the-back pass to Warren on a fast-break for an easy layup. The circumstances, Wallace said later, created a stark mandate for him to play well in the second half, and he more than delivered.

Playing his most aggressive and focused ball of the season, Wallace scored Vanderbilt’s first two baskets of the second half, an eight-foot jumper at the 19:13 mark and a ten-footer that gave the Commodores a 45–39 lead with 17:55 remaining. In his random encounter with Coach Crawford on an airplane two years earlier, Wallace posed a question to the Ole Miss coach: if I decide to go to Vanderbilt, what is the atmosphere going to be like in your arena? Crawford told him the fans would be hard on him, as they would throughout the South, and Wallace’s only remedy would be to tune out the hecklers and let his performance on the court do the talking. “You’re a great basketball player,” Crawford said, “and if you’re as good as I think you are, you’re going to shut them all up.” Whether or not Crawford remembered giving that advice, Wallace was heeding it, playing with a “steady, calm sense of determination.” With 14:33 remaining, he tipped in his own missed shot, then did exactly the same thing a minute later to ignite a 20-4 Vanderbilt run that put the game away for good. With just over two minutes left in the game, now playing completely without fear, Wallace stormed down court on a fast break and whipped the behind-the-back pass to Warren for an easy layup, a move that was completely out of character. This was all apparently too much to take for the Rebs, and on Vanderbilt’s next possession, Wallace was hacked in the back of the head by UM’s Larry Martindale, sending Wallace sprawling out of bounds. The foolishness of retaliation, Wallace said later, was “nonnegotiable and obvious.” Woozy from the blow, all he could do was stride to the free throw line and sink two shots. Finally, Skinner pulled him from the game, his line score reading six for twelve on field goals, two for two on free throws, three fouls, eleven rebounds, four turnovers, one assist, and fourteen points. Final score, Vanderbilt 90, Ole Miss 72. James Meredith had written that the most remarkable achievement of his time in Oxford was that he had survived. Perry Wallace could relate.

Strong Inside is available at bookstores and on Amazon or Barnes & Noble.com.