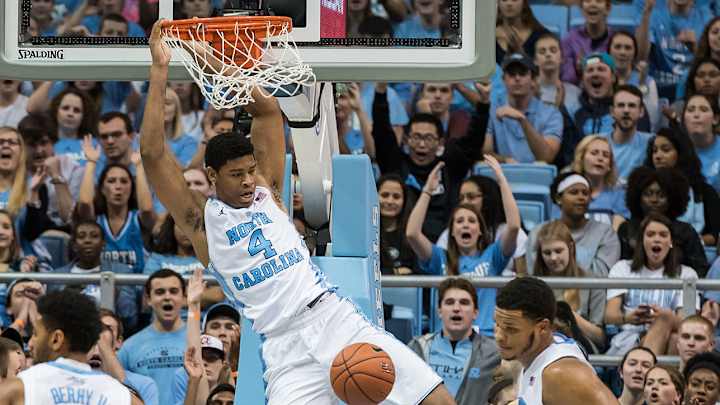

One shot: North Carolina's Isaiah Hicks has a last chance to make his own history

For one team, there was a rainstorm of confetti. An explosion of cheers. A dogpile of navy blue jerseys, all collapsing and swarming on the court at NRG Stadium in Houston.

For the other, only this: Bloodshot eyes, wrung completely out of tears. Heads hung. Bawling, because crying’s too common for such extraordinary sadness.

This was the scene after Villanova’s 77-74 win over North Carolina in last April’s NCAA championship game. It’s impossible to bring up that game without discussing the shot. The shot. The buzzer-beating, celebration-commencing three-pointer from Villanova’s Kris Jenkins that gave the Wildcats their first national title in 31 years.

But the game had heroics even before Jenkins made his 25-foot dagger. A double-clutch three-pointer by Tar Heels guard Marcus Paige had tied the game with 4.7 seconds left, seemingly guaranteeing overtime. The Wildcats called their last timeout, and both teams charted a final play.

North Carolina coach Roy Williams, worried that Villanova would go for a full-court heave and a layup, instructed three players—Paige and forwards Justin Jackson and Brice Johnson—to stand in the paint. That left point guard Joel Berry II and the 6'9" Isaiah Hicks on Villanova counterparts Ryan Arcidiacono and Daniel Ochefu.

One more thing: Jenkins, the inbounder. He was Johnson’s man. If Jenkins trailed the play, Johnson’s job was to leave the paint to go out and guard him.

So time unfroze, those 4.7 seconds all that remained. The whistle blew. Jenkins passed the ball in to Arcidiacono, who dribbled down the floor. He made it to the crest of the Final Four logo at midcourt before Hicks stepped away from his man to help. But then Arcidiacono turned his back to Berry and screened him, shoveling the ball to a trailing Jenkins. Johnson, meant to have left the paint to defend him, was nowhere near the play.

Hicks saw the pass, saw Jenkins rise to shoot, saw the release. He lunged. Then he saw it soar true, out of Jenkins’ hand and through the net right as the buzzer blared.

It was magnificent. It was heartbreaking.

Pictures and videos of the game-winning shot soon went viral. Jenkins became a household name, immortalized on the cover of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED with the ball leaving his hands. But what of the other man in the photo, the one on the other end of what is already college basketball’s most legendary dagger?

What of Isaiah Hicks?

*****

There was no spotlight, no newfound fame for Hicks to accommodate. Instead there were two weeks of free time after the loss, and ever since, hours spent toiling in the gym. Hicks, normally inclined to go home to nearby Oxford, N.C., over the summer, instead chose to stay in Chapel Hill, honing his craft. He even did so against the very man who so rededicated him to improving. Nate Britt, one of North Carolina's other returning seniors, is Jenkins’ adopted brother, so when Jenkins visited Chapel Hill over the summer, Britt asked the team if his brother could join their game of pick-up. Hicks said yes.

Jenkins' unforgettable shot set into motion Hicks' entire summer and possibly his senior year. The play itself will endure in perpetuity, but in the minds of those closest to Hicks, so will what followed it.

Fingers were pointed, as happens after losses, especially ones of such magnitude, and most of them went in Hicks' direction. He should have jumped sooner or reacted faster or done something, done anything, to stop Jenkins’ shot.

So in the locker room after the game, Hicks swallowed all the blame. Throngs of reporters invaded his locker and his peace of mind, probing him with cameras and microphones and questions of liability.

"I guess they were trying to see whose fault it was," Hicks says. "I was just like, ‘Well, I’ll say it was my fault.’ I mean honestly it didn’t matter to me. I’ll take the blame."

It was admirable, but also unjust. "I hated to see that he started taking responsibility," Williams says. "If somebody blames him, they don’t know what’s going on. It wasn’t his man but he got closer to him and challenged more than anybody else did. Kris Jenkins made that shot against North Carolina. It was not against Isaiah Hicks."

Philadelphia Threedom: How Villanova became the national champion

The day after the game, Williams called a team meeting back in Chapel Hill to address the issue. He’d never done it before, but he wanted to reassure Hicks that the loss wasn’t his burden to carry alone. He shouldn’t live with that. No one should.

That was early April. More than half a year has passed. Hicks doesn’t think much about the shot now, even if the rest of the college basketball world will never stop thinking about it. It's not much that he’s nonplussed by what happened; rather, he just doesn’t have time to dwell or mope. He’s too focused on a new season to let the last one bog him down.

This will be Hicks final year as a Tar Heel. North Carolina is ranked No. 6 in the AP poll, with three returning three starters (Berry II, Jackson and Meeks) from last season’s squad. A trip back to the Final Four is within reach.

But to make it back to the sport's biggest stage, the Tar Heels will have to do so without two of the biggest reasons they got there a year ago. Both Paige, the school’s career leader in three-point field-goals, and Johnson, a consensus first-team All-America who was selected by the Clippers in the first round of the NBA draft, are gone. Johnson led last year’s Tar Heels in points (17.0) and rebounds (an ACC-best 10.4) per game. Hicks, meanwhile, averaged a more modest 8.9 points and 4.6 rebounds in 18.1 minutes per game.

So in addition to being on the wrong side of one of college basketball’s most indelible moments, Hicks must emerge from the shadow of his former teammate, his friend, now deservingly called one of UNC’s best players ever. He is now the the man tasked with turning last season’s silver into gold.

"Basically, that’s what Coach (Williams) is telling me," Hicks says. "'It’s your time to step up, to be a leader. You’re a senior now. Everyone’s looking up to you.'"

He pauses.

"That’s what I’m working on," he says. "I have to now."

*****

Four hours before the national championship game was set to tip off on April 4, the Tar Heels gathered for one final team dinner. Williams dismissed his players afterward, giving them an hour or two of free time. Some retreated to their rooms in Houston’s Hilton Post Oak Hotel to nap. Others went about their own individual pregame rituals.

Hicks did neither.

He and his immediate family—older brothers Thomas and Allen, plus Allen’s father (also named Allen), as well as Isaiah’s parents, Regina and Thomas—instead ventured to the team’s adopted lounge, a converted ballroom on the first floor of their hotel.

It was oblong with high ceilings, filled with dark leather couches and video game systems and an unlimited candy supply in the far right corner. The Tar Heels had needed the jar of miniature Reese's cups refilled more than once that weekend.

In the center of it all was a ping-pong table, royal blue with a delicate white trim. Before anyone played, the family prayed. Regina gave her son a hug. Then Hicks—UNC’s self-proclaimed second-best table tennis player, behind only fellow forward Luke Maye—started playing doubles with his family.

"He was trying to take that edge off by not concentrating too hard," Regina says. "It was really cool to see how calm he was. Like, this is the [day of the] championship game."

Time passed. Time got away. Then a basketball staffer walked into the room. Hicks had to stop so he could go to the arena.

"But up until the last minute, we were all just playing ping-pong," says his brother Allen. "He was the only one in there that late before they had to suit up."

No, the ACC Sixth Man of the Year was never really in danger of missing the national championship game. But that he had to be told it was game time?

"He kind of vibes out on his own," says senior center Kennedy Meeks, Hicks' longtime roommate. "Most of the time he’s just to himself, man."

"He doesn’t do what everybody else does," Maye adds. "He just does him and that’s something not a lot of people do in this day and age."

ACC preview: Duke's depth & talent put it at top of conference

Perhaps that’s because Hicks grew up in Oxford, a rural town of fewer than 9,000 people. Perhaps it’s because he’s a homebody who clung to his mother's side so tightly as a kid that he earned the moniker ‘hip-baby.’ Or because he’s more interested in playing Call of Duty and catching Pokémon or sleeping for hours on end than partying or staying out late on Franklin Street, downtown Chapel Hill’s main stretch of bars and restaurants.

"I guess I’m a different person from everybody else," Hicks says. "I guess I’m more simple. I’ve always been a naturally quiet person. I don’t say nothing sometimes."

Hicks won't need to be a vocal leader this year either, but if Carolina has any hopes of matching last year's success, which also included ACC regular season and tournament titles, he will need to elevate his play. He’ll need to foul less, score more. Be a reliable force on both offense and defense.

The question—Can he?—is simple. The answer may not be.

*****

Isaiah Hicks’ journey to the cusp of stardom goes back to a three-bedroom house in Oxford. His parents slept in one room, his three older brothers (Allen, Thomas and Da’Shawn) in another, and Isaiah and his older sister, Latisha, in the third one. They all had bunk beds. Isaiah slept on the bottom.

During the days, he played. Imagined. He got to be a kid. He’d ride go karts with his brothers or practice trampoline flips in the backyard. Or maybe they’d go roller blading one day, or ride four wheelers. If Isaiah was lucky, his parents would drive all the kids to one of his favorite places: The Museum of Life and Science in nearby Durham.

Regina and Isaiah’s father Thomas also made a point of taking family trips. They’d take off time from work—Regina from her job as a pharmacy technician, Thomas from watching patients at Central Regional Hospital—and just drive. They visited Tennessee, the Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C., the beaches of South Carolina. Where they went was less important than that they went at all. Always together. Always as a family.

Hicks' basketball story started with family, too, in a cramped YMCA gymnasium in Henderson, N.C. His brothers used to shoot around there, run fives with the locals. They never let Isaiah play. "He was always the littlest one," Allen says. "He was always the last person on the court, nobody wanted to pick him up, and he’d wind up having to play by himself over against the goal. He did that a lot."

But Hicks didn’t let that deter him. He loved basketball, and basketball he’d play, even if it meant relegation to the corner, dribbling all by his lonesome.

In Northern Granville Middle School, he sprouted to six feet tall, and he won the unofficial yet undoubtedly important race to dunk first in the seventh grade. In 2009 he moved to Oxford's Webb High School and was a starter his very first game. Division-I programs—Florida, Kentucky and Louisville, among others—came calling soon after, but not North Carolina.

No. 6 North Carolina Tar Heels

He begged his mother to help him do something to earn Williams’ attention. Regina obliged, submitting a recruiting questionnaire to UNC. Williams took notice and eventually invited him to Chapel Hill to scrimmage in the summer of 2011. Isaiah had just finished his sophomore year of high school, but he suited up alongside current NBA players Harrison Barnes, John Henson and Tyler Zeller.

Williams finally extended Hicks the scholarship offer he so coveted on Aug. 8, 2011. On the car ride home that same day, about an hour up Interstate-85, the family stopped at a grocery store. Hicks stayed in the car and called Coach Williams. He didn't need to think about it any longer. He would be a Tar Heel.

"That’s unusual to say the least," Williams said of Hicks' quick acceptance.

"I wish he would’ve looked at some more schools before he chose UNC," Regina says, "only because they already had power forwards. You want to go to a school that doesn’t have your position so maybe you can start.”

Indeed, North Carolina had signed two big men in the class before him (Johnson and 6'11" Joel James) and added the 6'9" Meeks alongside him in the class of 2013. Hicks never wavered in his commitment.

In his final high school game, the 2013 3-A state championship, Hicks showed the dominance that earned him a McDonald’s All-American selection. He went for 34 points and 30 rebounds, adding seven blocks for good measure. The Warriors beat Statesville High 73-70 in overtime, even though Hicks fouled out with a few minutes left in extra time.

The final buzzer sounded. Webb's players rushed the court, stumbling over each other in celebration.

Isaiah didn’t join. He stayed seated on the bench, taking it all in.

"But you could see the relief on his face," Regina says. "You could see that he was just as happy as them, and then I saw that little one tear in his eye."

*****

Three years later, when the final buzzer sounded that night in Houston, Hicks watched another celebration unfold: that of Jenkins and his Villanova teammates. He walked glumly by them. There would be no sixth national championship for North Carolina. Hicks headed to the locker room deep in the bowels of the stadium, to be with the people who would remember more than just the last play.

"He was the guy who got the block; he was the guy that saved the ball out of bounds," Meeks says of Hicks' consecutive defensive stops with about four minutes to go. First he had blocked Josh Hart’s layup attempt, and then he corralled a rebound on the next possession just before it flew out of bounds. "But nobody remembers that," Meeks says, "and of course they won’t when it’s such a great shot."

They also likely won’t remember the touch foul Hicks was called for against Villanova’s Phil Booth with about 35 seconds left and the Wildcats up by one. A stop there would’ve given UNC a chance to win the game in regulation, but instead, Booth sank both free throws to give Villanova a 72-69 lead. That inconsistency, that give and take, is one reason questions still linger about this season’s Tar Heels.

Chief among them is whether Hicks, who averaged 6.7 fouls per 40 minutes, can even stay on the floor. And if he can, can he realistically replace Johnson? He has become a much more assertive player than when he arrived in Chapel Hill and has shown marked improvement every season, particularly with his strength and offensive repertoire. But he has never been the rebounding force his size and athleticism suggests he should be, and he has started just six games in his career, with career averages—weighted down by a freshman season as a little-used reserve and a sophomore season as not much more than that—of a paltry 5.8 points and 3.0 rebounds.

"I’m not gonna try to compare Isaiah to Brice," Williams says. "I’m gonna try to get Isaiah to be the best player he can be."

"No one can truly replace Brice," Paige adds, "because he had one of the five or six best seasons in the country last year. (Isaiah) just hasn’t had as many opportunities as some of those other guys."

But what about when he has those opportunities, as he surely will this year? What then?

"He’s just got to stay out of foul trouble," Meeks says. "Other than that, I could really see him being as good as or [better] job of what Brice did.”

If North Carolina is going to play on Monday Night again Hicks will have to. He’ll have to outrun his ghosts—of Kris Jenkins, that last shot, falling short of expectations—and if he can't he’ll at least have to box them out in the low post.

There’s no way to know for certain how this story ends, whether or not Hicks can create a legacy outside of that moment in April. There are two reasons, however, to believe that he will, and both came shortly after he became a footnote to history.

The first is a speech given to the team after the game by Michael Jordan, a UNC graduate whose own historic shot gave the Tar Heels the 1982 NCAA title. Failures happen, he said. Losing is just a part of winning.

"That really spoke to me," Hicks says. "I can’t dwell on it. I just have to live with it."

Then came the second clue of the night, when Hicks found his mother. She consoled her son, told him he’d tried his hardest. Hicks didn’t need to be comforted.

"He was fine," Regina says. "He said, 'It’s OK. I’m gonna be back to the championship game.'" She remembers laughing. Skepticism. And then he said it again, with an almost unwarranted confidence.

"I’m gonna come back here."

Brendan Marks is a senior at the University of North Carolina. This is his first story for SI.com. Follow him on Twitter here.