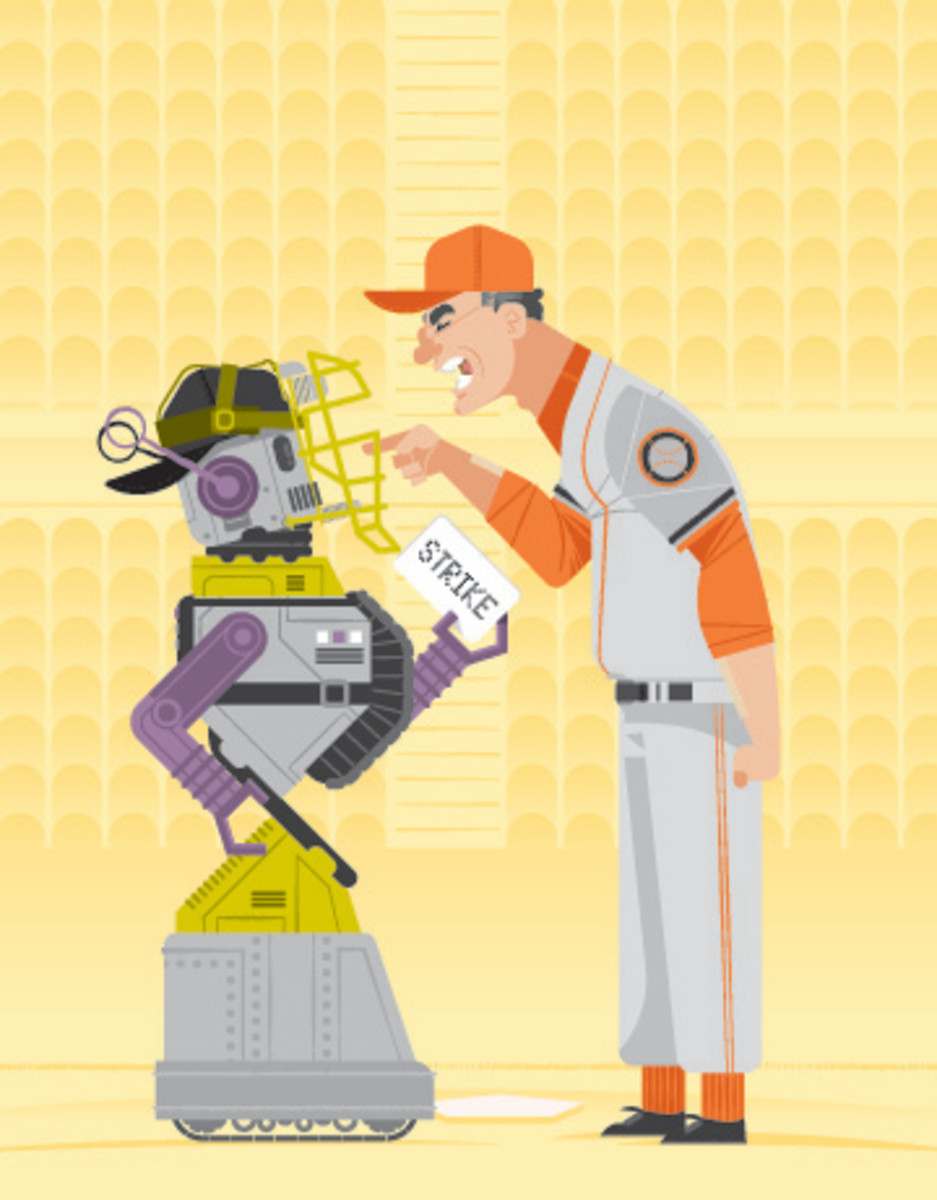

Is MLB Ready for Robo-Umps and an Automated Strike Zone?

We are sad to inform you that the robo-ump looks nothing like you had hoped. A black box, glossy like a television screen that is never turned on, and positioned high behind home plate, it looks like an extremely unsubtle security camera. Tracking pitches using radar, it distinguishes balls from strikes and communicates the determination to the ump on the field—still a standard-issue human, now with an earpiece and an iPhone—who gives voice to the call. Not exactly the robotic overlord of your sci-fi dreams.

The system made its debut just this summer, in the independent Atlantic League, but its march across baseball is starting to look inevitable. MLB followed that initial testing by instituting the robo-ump in the Arizona Fall League in September. And just a week after the conclusion of the World Series—where an automated strike zone became a hot-button issue, thanks to controversial calls in Game 5—commissioner Rob Manfred announced that the tech would arrive in select minor league parks in 2020.

The robo-ump exists in the name of better baseball, offering a strike zone that is totally consistent, not just from hitter to hitter, but from team to team, game to game, season to season. It irons out any potential for human ambiguity. In theory, this should make it impossible to find fault. In practice . . . it's trickier.

"As my dad put it: You know, for a hundred years, you go to a game, you have a couple beers, you have a hot dog, you yell at the umpire," Atlantic League ump Tim Detwiler told SI days before the automated strike zone debuted there. "My old man said, "Who's going to yell at the computer?'"

Two weeks later, Detwiler became the first umpire in the history of organized baseball to eject a person for yelling at the computer.

That person was former Cy Young winner Frank Viola, now a pitching coach, who, to be fair, yelled at not only the computer (for what he felt were bad calls) but also at Detwiler (for not manually overriding those bad calls, which he is allowed to do on pitches that bounce or on checked swings). And though he was first, Viola wouldn't be the last; Arizona Fall League yielded at least one ejection for arguing with the robo-ump.

Reactions like this can be explained in part by the human desire to be correct, to believe our own eyes and yell at anyone (or anything) who tries to tell us differently. But part of it is that the robo-ump's truth is different from the truth that baseball is used to. It's "perfect"—a zone that is as free from human error as it is from human grace and context.

This, in a sense, is similar to any number of recent moves in baseball. The robo-ump will optimize strike calls just as the shift has optimized defensive positioning, as the fly ball movement has optimized hitting, as all sorts of data have optimized relief strategy. It will strip out error as pace-of-play initiatives have stripped out dead time. The result is a game that is more efficient, closer to the truth, supposedly better.

But the robo-ump takes this one step further by not optimizing the performance of people on the field but by writing them out altogether. You can argue that any game official's performance is incidental rather than intrinsic to the action, but it's a more difficult argument to make for baseball. The umpire's judgment is not rendered on an as-needed basis; it's mandated on every pitch. The ump is included in the rule book's own definition of baseball (Rule 1.01: "Baseball is a game between two teams of nine players each, under direction of a manager, played on an enclosed field in accordance with these rules, under the jurisdiction of one or more umpires"), and yet here, in arguably his central function, he's disappearing entirely.

Which takes the whole discussion somewhere existential. What's the end result of a game whose governing principle is efficiency? It's a smoother, more accurate game. But is that better?

"It's part of the game," Nationals outfielder Adam Eaton said of umpire error after Game 5 of the World Series, in which his team lost out on several questionable calls. "It's what makes baseball great. Sometimes you're on the bad end of it, and it's not all that fun, but that's baseball."

For now, yes, but maybe not for long.

This article appears in the Nov 18-25, 2019 issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.