Off the Grid: The NFL's credibility gap, Jim Bob's Big Adventure, and more

Welcome to the debut of Off the Grid, where we'll delve into two major issues the league needs to fix, chat with one of Andy Dalton’s pieces of armor, examine Jim Bob Cooter’s rising star in Detroit, point out a small-school QB who should be on the radar of several NFL teams, and more. Let’s begin at 345 Park Avenue...

Despite the best efforts of its leviathan PR department and seemingly bulletproof status as the purveyors of America’s game, the NFL is facing serious credibility and accountability issues on two important fronts—the comprehensiveness of its concussion protocol, and the accuracy and integrity of its officiating. I wrote about the flaws in the current concussion protocol after Rams quarterback Case Keenum was hung out to dry after an obvious in-game head injury against the Ravens on Nov. 22. The Rams were not punished at all despite the fact that they had a complete and total system failure in the Keenum incident—the NFL’s big response was to schedule a conference call with all 32 head team trainers for a refresher course in the current protocol.

How will NFL improve concussion problem over the next 50 years?

Less than a week later, Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger had to self-report a concussion during a game against the Seahawks. That Roethlisberger’s self-reporting was seen in some quarters as a major step forward is a pretty decent indicator of how backward things have been with the league’s in-game concussion management throughout its entire history. I made the point that little seems to have changed since the Colt McCoy incident in 2011 that caused the NFL to at least, on its surface, make more of an effort to ensure that players with obvious possible concussions will be tested comprehensively and taken out of games as soon as possible.

And last Sunday, Matt Schaub suffered what looked to be “concussion-like symptoms” (to use the league’s parlance) with 3:01 left in the first half when he was slammed to the turf by Dolphins defensive end Derrick Shelby after he rolled right and threw the ball away. Schaub put both hands to his head immediately, referee John Parry helped him up from the turf, and Schaub stayed in the game throughout the rest of the first half and into the third quarter.

The in-game protocol is supposed to protect a player right after he’s suffered any serious blow to the head, especially after he exhibits any sort of pain response (like putting his hands to his head), yet Schaub stayed in the game. There wasn’t a one-play pause for backup quarterback Jimmy Clausen to come in—he didn’t replace Schaub until later. At that point, Clausen stood up, but he still had his Ravens baseball cap on. Baltimore huddled and went straight to the next play. There’s no evidence of anyone from the Ravens’ medical staff going onto the field to observe Schaub’s status.

Still, Harbaugh on Monday maintained that the Ravens followed the concussion protocol “to a ‘T’.”

Okay. So, what happened when? When exactly was Schaub determined to be fit to continue playing?

“I don’t know,” Harbaugh concluded. “I haven’t delved into that too seriously. It’s not my area of expertise ... I know mistakes have been made—I understand that—but I think you trust professionals to do their job and respect the fact that they know what they’re doing, and they did a good job on this one. So, we feel good about that.”

• PRICE: Physical, emotional pain can’t keep Jason Witten off the field

As an update, I asked Harbaugh specifically on Wednesday morning about the process of evaluating Schaub, and if he was happy with the way things went with two more days to review it.

“Yeah, I was,” Harbaugh said. “I’m not a protocol expert by any stretch; we just adhere to it as we’re told to. Right away on the sideline, we saw it, our trainers saw it, and our coaches saw it. Our trainer went right out on the field and talked to Matt, and he said he was good. The trainer said he was good. The NFL representative saw it, and he started their protocol and went through it. They went through it again at halftime and passed him, went through it after the game and passed it, and then went through it the next morning and passed it. All indications are that Matt did not have a concussion, and Matt said he didn’t have a concussion, so it seemed to me that the system worked the way it was supposed to.”

OK, but if the system worked, I posited, the trainer and the NFL rep would have seen to Schaub right away, and it doesn’t look like that on the tape.

“It was at some point in time there—he went out and talked to him. I don't know exactly the timing of it.”

As I’ve written before, I don’t think NFL coaches are in league to put players they know to be concussed in compromising positions. This isn’t an evil conspiracy—more accurately, it appears to be a “Confederacy of Dunces” (to title-quote the great John Kennedy Toole) in which nobody knows what anybody else is doing. If Schaub didn’t have a concussion, great. Good for him. But that doesn’t let the NFL off the hook. Put simply, the NFL has tasked itself to do better, and it’s failed fairly miserably.

As for the at-times comical officiating this season, there are two schools of thought: One is that officials in today’s NFL are so paralyzed by the league’s ever more complex rules and review processes, it’s no wonder they’re screwing up more than ever. The other school of thought tells us that officiating has always been error-prone, and the advancement of technology simply makes those errors more glaringly obvious.

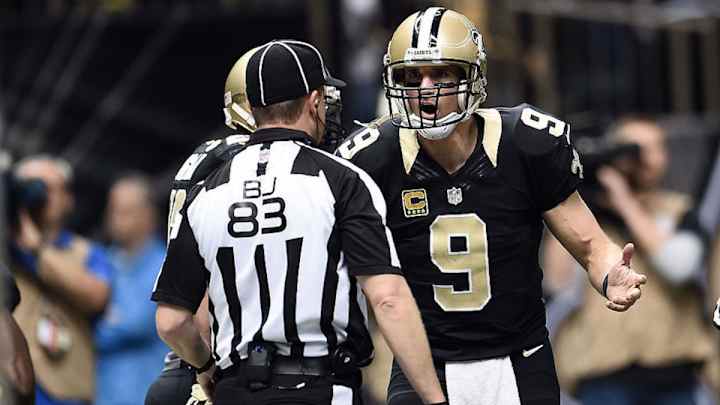

I tend to lean between the schools of thought, but in his team’s 41–38 loss to the Panthers last Sunday, Saints coach Sean Payton said that there were three instances in which Carolina huddled with 12 men—all in key moments—and none of the instances brought flags from Brad Allen’s officiating crew. On Monday, after talking with NFL VP of Officiating Dean Blandino, Payton was still unhappy when he appeared before the local media.

“We don’t come in on Mondays and just have angst half of the day about calls. But today was one of those mornings where [it’s difficult]. Someone sent me the TV copy and you have to be able to get that. The fourth-and-one becomes fourth-and-six. That’s the first time that it happens. [On the goal-to-go situation], they put 12 on the line of scrimmage. 12 break the huddle and 12 go to the line of scrimmage. The third time around, it happens on the final game-winning drive. They break the huddle and player 12 continues onto the sideline.”

Would those flags have made a difference? In a tight game, it’s hard to say. But we’re already deep into a season in which two different teamswon close games they shouldn’t have—the Jaguars over the Ravens and the Raiders over the Titans—based directly on poor officiating. And the gaffes seem to be more prevalent than ever.

Is that an issue of perception? To a point. But the league also wants its officiating crews to be younger and more athletic, and when you cross that fact with the reality of the league’s rules changes and explanations are more complicated than ever, you’re going to have issues.

Problem is, the NFL doesn’t seem to see these problems as problems. There have been fines and demotions, but the league’s practice of downgrading an officiating crew to a lower-profile game isn't always a punishment. The NFL demoted Pete Morelli’s crew from the Colts–Steelers game last Sunday to the Eagles-Patriots game after a number of obvious blunders in Arizona’s Week 12 win over San Francisco. (Morelli’s crew also missed a false start that would have turned the Jaguars’ win over the Ravens in the other direction). As it turned out, the Steelers thrashed the Colts in a Sunday night laugher, while Philly’s upset over the Patriots was probably the most compelling game of the day.

And when Goodell was asked last week about the state of officiating, the response was fairly typical of the commish: Things are great, and we’re getting better! (Ironically, Goodell has been throwing that party line out there about concussions and player safety for years).

“When we talk about integrity of the game, it’s one thing that truly affects the integrity of the game,” Goodell said after a recent owners’ meeting. “We strive for perfection. We strive for consistency. We’re not going to always get that, but we’re always going to continue to try to get that. Our commitment is to do everything reasonable to make sure that we improve officiating.”

Goodell then said that the need is to “try to avoid those mistakes as much as possible, train them differently, improve the quality of the officiating and use technology to help them when a mistake does occur,” and maintained that his refs do “an extraordinary job.”

“I think what we see now through technology is we see things we could never see before,” Goodell said. “But I think what it does is it validates the quality of our officiating.”

Well, not really. Just as the truthful response to the question, “Has the NFL improved its concussion protocol in the four years that it’s been insistent on doing so?” is a conclusive “not really.”

And what’s interesting is that a league that has no issue fining players over the smallest infractions seems to get weak in the knees when it comes to doling out discipline in response to breakdowns in the structure of its own business. If you want to see improvement in officiating or enacting concussion protocol, perhaps the answer is to do to teams and officiating crews what you do to the players. Crews that miss glaringly obvious calls get fined on a scale based on the degree of infraction, and if your call or non-call is determined to have cost the team that should have won a game, you may be reffing for half-price the next weekend.

Similarly, the league’s refusal to take more severe action against teams in clear violation of the concussion protocol is a disservice. Maybe a team who leaves a player on the field without testing him when there are clear concussion risks should lose a few draft picks? Guaranteed, you’d see the overall process pick up a bit.

There are not simple one-track solutions here, but policies which demand the same level of accountability from teams and officiating crews as is demanded of players would be a good start.

Five Questions For...Bengals RT Andre Smith

Former Alabama offensive tackle Andre Smith was considered to be a sure high first-rounder in the 2009 draft, and he was taken by Cincinnati with the sixth pick, but that didn't come without issues. He left his combine early to work toward his pro day, and his performance there wasn’t great. Still, Smith overcame that and some early blocking issues to become, when healthy, a pretty good offensive lineman. I recently talked with him about that journey, and why his Bengals are in a great place now.

Doug Farrar: I wanted to start with the combine and pro day story...

Andre Smith: [laughs] Oh, man—I thought that was water under the bridge!

DF: Well, it is, but I want to ask you what you learned from it, and what you would tell 2016 draft prospects about how to handle themselves through the pre-draft process.

AS: Just that it is a process, and you have to go through it. You can't be...you have to learn to be smart, and be a pro at all times. Just making the right decisions, is probably the most important thing I would tell anybody. There will be people all over you, thinking they know what's best for you. It's a learning process, and you're moving so fast. If you're not thinking things out thoroughly, and not being an adult, as I should have been... that's what I learned from it. There were a lot of growing pains early on in my career."

DF: You were in a fairly complex and successful offense at Alabama, but when you graduated to the NFL, what were the things that were most important for you to learn?

AS: For me, it wasn't really the offense. I can play football, and I knew that. It was just being in a different environment, that was the biggest adjustment for me. When it came to the Xs and Os, I know that I just had to work at it, and it would happen.

DF: What is it that's special about this Bengals team? You guys are 10-2, and the AFC's top seed as we speak.

AS: I would say that it's the family-type environment we have in our locker room—the camaraderie we have among each other. Just the want to do well for one another. Whether it's A.J. [Green] and the receivers blocking downfield so that our running backs can score touchdowns... just different ways to help each other be successful on the field. That's how most teams are successful. It's the same on defense—the way they've been playing and running to the ball, and working together as a unit. We just love each other, and we want to see each other be successful.

DF:Andy Dalton's obviously been a very talked-about player in recent years. Everybody seems to be waiting for the jump to the next level—for him to do in the postseason what he generally does in the regular season. Every preseason, we hear that he's turning the corner as a quarterback and as a leader. If that's the case this year, what's different?

AS: It's his command of us to be at our best at all times. Putting guys in the right place if we mess up, and demanding that we be great around him. We know that if we keep Andy clean, we're going to be successful. The way he comes into work—whether it's on the practice field or breaking down film as a unit, he's just spot-on. He's just grown into the great leader that he is.

DF: You're going to be a free agent in 2016. Give me the sales pitch for Andre Smith, the person and the player, for prospective NFL employers.

AS: Well, great person on and off the field, and I'm not going to do anything to give a black eye to the organization or myself. You're going to get a guy who comes in and works every day. Great leader on and off the field. I'm a passionate guy who loves the game of football—I dream, eat, sleep football all day. As a player, I think I do everything well—run-blocking and pass-blocking. I feel like I can go one-on-one with anybody.

The All-22: Jim Bob's Big Adventure

Yes, new Lions offensive coordinator Jim Bob Cooter has the best name in sports—quite possibly the best name in sports history—but he's also done a pretty bang-up job since he was promoted on Oct. 26 following Detroit's decision to fire Joe Lombardi in late October. Since Cooter's move up from quarterbacks coach, the Lions' offense has regained its formerly combustible ways, and Matthew Stafford has been the biggest beneficiary. Stafford has a 105.4 quarterback rating over that period of time (sixth-best in the league), and has thrown nine touchdown passes to one interception throughout November and December. That's a big improvement from the first half of Stafford's season, when he posted an 84.1 rating and threw 11 touchdown passes to six picks.

Week 14 NFL Power Rankings: Gronk-less Patriots tumble three spots

The difference with Cooter seems to be more philosophical than schematic—in the pre-Cooter era and the current day, the plan has been to circulate the ball efficiently as opposed to throwing it deep and seeing what happens. But Cooter is using input from his players to put them in positions to succeed, and as a result, he's putting a more varied offense on the field than Lombardi ever did. New formations, more shotgun—whatever makes Stafford more comfortable and fits Cooter's overall concepts.

Perhaps the best example of this came in Detroit's 45-7 beatdown of the Eagles on Thanksgiving Day. Stafford threw five touchdown passes, and those scores came from all kinds of different concepts. Not that everything was so terribly complicated, but the schemes set up Stafford with easy opening reads and the ability to find his best players in space. Let's look at the first two touchdowns:

The first score came with 2:14 left in the first quarter. The Lions were in a Pistol two-back set against Philly's single-high safety look. Running back Theo Riddick, perhaps the league's best receiving back this season, is to Stafford's left. Calvin Johnson is wide left. The plan here is to get safety Walter Thurmond to bite on the end zone corner route that Johnson's running, leaving Riddick to be covered one-on-one by linebacker Mychal Kendricks. If Thurmond stays home, that's a one-on-one matchup for Johnson against cornerback Nolan Carroll. Either way, the Lions win, especially if the Eagles run a blitz. In this case, the win was an eight-yard touchdown to Riddick, with Kendricks sucking wind trying to keep up.

“Really good, very, very good,” Cooter said on Nov. 30 of Riddick as a route-runner. “Really tough to cover one-on-one. We’ve been around here a year and a half, going on two years at this point, it’s a rare thing to see a guy cover him one-on-one when you give him a couple of ways to break and you get him in the open field a little bit. So he’s a really impressive route runner. He’s got a really natural instinct for getting open that’s hard to teach. You can draw routes on the board, you can show tape of guys running routes, but he just has an instinct for getting the guy moving one direction and going back the other one and vice versa. So he’s got a good feel for that stuff.”

The second touchdown came with 7:58 left in the first half. This two-yard scoring pass to receiver Golden Tate is a nice example of how Cooter likes to move his weapons around pre-snap to create formation advantages, and deploy them after the snap to their best advantage. Tate motions from left slot to the fullback position in a closed red-zone formation, and then runs past the pass rush and underneath the coverage into the flat for an easy score.

“Yeah, we’ve had that up for a little while here," Cooter said. "It’s actually a pass concept we’ve had in for years and years around here. We’ve just kind of been tweaking the personnel groupings of that thing. We’ve actually carried that play on our call sheet the last three, four, five weeks, I don’t know how long. It’s been up, this just really felt like a good week to kind of move it up the call sheet just because of the way they play down there, we thought we would have a good chance to maybe pop him free out into the flat, which is not always easy. It depends on different defensive looks that they play. So we thought this would be a good week for that, and it turned out to be the right call.”

Indeed. Funny name? You bet. But Jim Bob Cooter is much more than a punchline—he appears to be one of the brightest young offensive minds in the game.

Prospect of the Week: Carson Wentz, QB, North Dakota State

My colleague Chris Burke and I will get heavy into the pre-draft process once again after the Super Bowl, with the SI 64 player rankings and reports, and all kinds of other stuff. But this space is a good place to get things rolling with a few words each week on a prospect that's caught my eye.

We'll get started with North Dakota State quarterback Carson Wentz, who unfortunately broke a bone in his throwing wrist and will miss the rest of the 2015 season. But that shouldn't affect his ability to work out at the combine and his pro day, and he's a pretty intriguing guy in a quarterback class that doesn't yet have a clear alpha dog.

At 6'5" and 231 pounds, Wentz shows an interesting combination of established strengths and future potential. He's got the arm to make any throw, as seen by the across-the-body bullets he completes on a fairly regular basis. And he's athletic enough to be a factor in an NFL option package, or run a heavy boot-action offense to perfection. The former skill puts him in the sights of the 49ers and Eagles, at least. The Broncos certainly love tall quarterbacks with big arms who run boot action, as Brock Osweiler's ascent has proven. He can throw on the move in a college offense, and he's a good runner—you'll see him making jump cuts and bulling through tackles for first downs on a fairly regular basis.

The downside? Wentz will have to prove that he can run a full, complex NFL offense —even the Chip Kelly version is far more advanced than what you see the Bison using. Like a lot of college quarterbacks, Wentz tends to telegraph his passes, and there will be serious concerns about his strength of opponent. But as a mid-round guy, maybe even a late-second-round guy, I really like his athletic potential.

History Lesson: The option route

Option routes are common in the NFL now—routes which allow the receiver to change his route based on coverage—but that wasn’t always the case. I’ve written previously about importance of the option route in the modern NFL. The Don Coryell Chargers of the 1970s and 1980s, and a few other teams of that era, used them, but it was really the dawn of the run-and-shoot in the late 1980s that brought option routes into play. Glenn “Tiger” Ellison, the Ohio high-school coach who invented the offense in the 1950s, added option routes when he saw schoolyard kids simply adjust their routes based on the motions of their opponents.

How a book on stoicism became wildly popular at every level of the NFL

The differences in the NFL’s versions of the run-and-shoot were obvious, and effective. Before the West Coast offense, receivers primarily got open through their own physical gifts and intellectual guile—feints at the line of scrimmage, covert push-offs, pure downfield speed. Bill Walsh's offense directed its receivers to move in precision as part of a perfectly orchestrated symphony. In the run-and-shoot, the receivers were asked to define their routes on the defense's actions. Quarterbacks would make their first key off the safety closest to the line of scrimmage. If the safeties were deep, there was always a square-in to run underneath the coverage. If the receiver could beat the safety to the near side of the field, that could be the play right there.

“The concept of reading the coverage, nobody did it,” said June Jones, who was Mouse Davis’s quarterbacks and receivers coach in Detroit, and installed his own versions of the run-and-shoot in Houston and Atlanta over the years. “Even when I was a player in 1977, every Monday they'd say look at the next team and tell us what you think will work. Well, I’d write a book on reading and how to read the routes and all that stuff. But nobody in the NFL back then allowed their receivers to read coverage. If you're running a curl, you're running a curl. That was it. There was no conversion.”

Ellison created the base concept in the idea that the kids he was watching were simply adjusting their routes to what their defenders were doing. But in Davis’s offenses, the route conversions were manifold per receiver, and they defined the passing offense to a large degree. Each receiver had specific assignments to read against coverages, and the conversions were fairly complex. Against a two-deep nickel defense alone, as Davis detailed in one coaching clinic in the early 1990s, the possibilities were all over the place

“Our first key is the nickel back on the onside slot. If he [the nickel back] doesn’t bump over with the motion, we run the motion halfway between the Z and Y receivers, and get him uncovered 95 percent of the time. If you think they are going to bounce the coverage to the motion, it doesn't always happen. Sometimes, they want to rush the nickel back off the corner. If they don't bump over, we take the completion the defense gives us. When the nickel bounces to the motion, we go back to our original read against the Three-Deep pattern.

“If the split receiver goes deep, the cornerback goes with him. But if you are reading the corner, when he goes back, we throw the ball to the flat. If he rolls to the flat, we throw the ball outside to the split receiver. The quarterback delivers the ball on the third or fifth step. If the cornerback runs off with the split receiver and the nickel back jumps the flat after a bump on the [receiver's] motion, we have to go to the secondary route by the motion man. He is facing a half-field safety; he has to know that. When the motion man doesn't get the ball on the third step, he looks at the safety. If the safety man is right on his face, the receiver runs the post. He beats the safety through the hole in the middle of the field. If the motion man runs his pattern and the safety man is a damned mile up top, he breaks his pattern off into the middle short.”

Phew. That’s against one kind of coverage, with different specific options and read assignments against other kinds of coverages. The motion of the slot receiver gave the quarterback a clue as to whether the defenses were running man or zone coverages, but a lot of this deduction happened on the fly—which is why some mistook the run-and-shoot as a simple thing to stop, when in fact, the relative simplicity of base calls were a requirement for a highly nuanced post-snap offense. That’s what you see so often today, and while the run-and-shoot isn’t a base offense anymore, post-snap concepts are the key to today’s hurry-up offenses.

Turkey of the Week: Danny Kanell

The former Florida State and NFL quarterback, and current ESPN college football analyst, had quite the little Twitter rant on Tuesday morning.

The war on football is real. Not sure source but concussion alarmists are loving it. Liberal media loves it. Doesn't matter. It's real.

— Danny Kanell (@dannykanell) December 8, 2015

I really didn't want to give this more clicks but if u don't believe me...

— Danny Kanell (@dannykanell) December 8, 2015

Don’t Let Kids Play Football https://t.co/psAJ8Tk2VB

The “War on Football” he refers to (how dramatic!) is actually an op-ed piece in the New York Times penned by Dr. Bennet Omalu, the main character in the upcoming movie Concussion, and the man who discovered CTE. In the piece, Dr. Omalu opines that children should not be subjected to high-contact sports—such decisions should be made when their brains are fully developed, and they’ve reached the age of consent. It’s an interesting piece, and while I don’t agree with Dr. Omalu’s view entirely, he’s earned the benefit of the doubt with his comprehensive research—especially in the face of an NFL that did everything it could to discredit him.

When I pointed out to Kanell on Twitter that this wasn’t the liberal media attack he portrayed it to be—more the opinion of one individual who has probably done more to advance the honest concussion discussion than anyone else—this was his response.

.@SI_DougFarrar oh cool. So u agree with him then. Start writing it. No more football.

— Danny Kanell (@dannykanell) December 8, 2015

So much for informed debate. Kanell, who later revealed on his feed that his father, who was once the Yankees’ spring training orthopedist, held him out of football until he was 16. For safety reasons, but not because of concussions. Well, alrighty then.

Kanell was probably aiming for the ESPN car wash treatment, and he'll most likely get it.

SI.com contributing NFL writer and Seattle resident Doug Farrar started writing about football locally in 2002, and became Football Outsiders' West Coast NFL guy in 2006. He was fascinated by FO's idea to combine Bill James with Dr. Z, and wrote for the site for six years. He wrote a game-tape column called "Cover-2" for a number of years, and contributed to six editions of "Pro Football Prospectus" and the "Football Outsiders Almanac." In 2009, Doug was invited to join Yahoo Sports' NFL team, and covered Senior Bowls, scouting combines, Super Bowls, and all sorts of other things for Yahoo Sports and the Shutdown Corner blog through June, 2013. Doug received the proverbial offer he couldn't refuse from SI.com in 2013, and that was that. Doug has also written for the Seattle Times, the Washington Post, the New York Sun, FOX Sports, ESPN.com, and ESPN The Magazine. He also makes regular appearances on several local and national radio shows, and has hosted several podcasts over the years. He counts Dan Jenkins, Thomas Boswell, Frank Deford, Ralph Wiley, Peter King, and Bill Simmons as the writers who made him want to do this for a living. In his rare off-time, Doug can be found reading, hiking, working out, searching for new Hendrix, Who, and MC5 bootlegs, and wondering if the Mariners will ever be good again.