Paradise Squashed: How the NFL Ruthlessly Took Down the Pioneers of Online Sports Betting

Nikola Jokić is smiling as he towers over Jay Cohen. In the middle of downtown of an Eastern European city, the face of the NBA star adorns an enormous billboard for Superbet, a Slavic version of FanDuel. It’s silhouetted against a modest skyline, and Cohen doesn’t stop to look up as he walks by.

Having arrived at his destination to meet Sports Illustrated, Cohen makes one request: there be no mention of his specific whereabouts. “I don’t need any hassle,” he says. So let’s just say he lives outside this city, one that is still shaking off the torpor of the Soviet era.

Cohen likes it here fine, he says. It’s quiet. People are pleasant. More important, it’s the homeland of his wife and where their young son goes to school. But, you might say, Cohen, who grew up “a nice Jewish kid” on Long Island, is a gefilte fish out of water. He is still adjusting to a foreign language, foreign cuisine and foreign way of life. How’d he end up here? That Nikola Jokić billboard overhead provides a hell of a clue.

Cohen landed here in 2013. Since then, he has tried to find stable employment in tech or finance. He has applied for more than 2,000 jobs and is willing to work remotely or relocate for the right opportunity. But he’s had little luck. On the plus side, he is a Cal grad who studied nuclear engineering and has helped build a tech business once worth hundreds of millions of dollars. On the other side of the ledger, apart from being in his mid-50s, he must check “yes” when asked, “Have you ever been convicted of a crime?”

Last year Cohen found a posting at DraftKings for a job managing a team of NFL traders. Sheepishly, he applied. A few days later, he received an auto-response thanking him for his interest but noting that the company was “going with someone with more experience.”

With more amusement than self-pity or aggrandizement, he laughed when he got the rejection. Because a quarter century ago, before the NFL decided it needed to move heaven and earth—and the U.S. government—to stop him, Jay Cohen was at the forefront of online sports gambling. “Me not getting a job [at DraftKings] would be like Tesla or Edison getting turned down for a job at the electric company,” he says. “I helped invent the product!”

If, in the late 1990s, you were a small country looking for a growth sector that could goose your national economy, internet gambling was, well, a smart bet. Inside its perimeter of exquisite beaches, the leaders of the Caribbean island of Antigua decided that the country—long struggling for commerce—would set its sights on becoming “the Las Vegas of Internet Gambling.” As Gyneth McAllister, then the overseer of Antigua’s gambling industry, put it to SI in ’98, Antigua was going to thrive as a gambling hotbed “by keeping bad guys out and making sure players get paid.”

Initially, anyway, there was success. By the late ’90s, 80% of gaming websites came from servers based on Antigua. The gambling industry, as hoped, quickly became Antigua’s biggest source of employment outside of tourism for its 75,000 residents. In particular, Antigua became the epicenter for dozens of sites devoted to gambling on sports.

For decades, fans inclined to place bets on games, races and matches needed to either go to Vegas or consort with a neighborhood bookie. Suddenly, they simply needed a decent modem and dial-up access. While Antigua licensed established outfits—William Hill, Cantor Fitzgerald—it was also home to the most intriguing player in this emerging sector: World Sports Exchange.

In the mid-’90s, Steve Schillinger was a trader on the Pacific Stock Exchange. He did well the way most traders do well: hedging; arbitraging; spotting inefficiencies; and preying on the rash and heedless, the folks favoring intuition over data.

He also liked a friendly wager. In the spring of 1995, traders on the floor were speculating on the upcoming verdict in the O.J. Simpson murder trial. When the jurors declined to show up to court one day, suggesting a possible hung jury, traders who had bet on guilty tried to cut their losses. Schillinger realized there was something bigger at play.

So did a colleague, Jay Cohen. A star trader with a sixth sense for making markets, Cohen was pulling down $500,000 a year in his 20s. But he was seduced by the idea of launching a startup. The same principles he and Schillinger brought to bear in their day jobs? They could use them in a much more fun context, market-making and gauging probabilities for real-life events. Would Team X reach the NBA Finals? Would Movie Y hit a certain level of box office take? (Schillinger once won a 20-to-1 bet after Princess Diana died, correctly predicting that Elton John would write a song.)

Schillinger and Cohen recruited a third colleague, Haden Ware, an undergrad at Cal and member of the crew and lacrosse teams, who preferred the culture of the trading pit to his campus life across the Bay. The three began mapping out the variations and mutations for taking these bets online. The possibilities seemed limitless. And the pool of gamblers—“cyber-bettors,” in the late-’90s vernacular—wasn’t just the trader bros on the floor; they constituted, literally, a worldwide web. As one Austrian bookmaker told SI at the time, “Gambling is the future of the Internet. You can only look at so many dirty pictures.”

More critically, the three friends reckoned that they wouldn’t simply take bets on outcomes—Would O.J. be convicted? Would the Cowboys beat the Chiefs?—but would create a proper futures market, with fluctuating prices, rising and falling in real time based on changing events. It would be primarily sports, but also include pop culture. They rustled up $500,000 in seed investment, named their global startup World Sports Exchange and registered the eye-catching, subversive domain name www.wsex.com.

Owing to the 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), sports betting was prohibited outside of Nevada and the odd casino in Oregon and Delaware. Cohen, operating on guidance from a law firm and an accounting firm, decided they needed to move the business to Antigua.

There, online gambling wasn’t merely permitted, but welcome. If they based WSEX in Antigua, they believed, taking online bets from inside the United States—or anywhere in the world, for that matter—would be perfectly legal.

Especially for Cohen and Ware, bachelors yet to turn 30, the prospect of running a new business from a Caribbean island didn’t sound half-bad. (Though both now recall working around the clock, they lived first at a villa, then at a hotel, where Ware would end up dating the woman who worked the front desk.)

World Sports Exchange paid an annual licensing fee to Antigua of $25,000 (eventually $75,000, then bumped to $100,000), which enabled the company to take bets from anywhere worldwide. “We were really pushing to do this legitimately,” says Ware. “There were tens of thousands of illegal bookmakers back in the United States that were strong-arming people. We were taking credit cards. We were doing age verification. We were doing things that just didn’t exist in the normal bookmaking circles.”

The U.S. seemed to agree that WSEX was beyond its control. In 1998, asked about online betting, Department of Justice spokesman John Russell told The New York Times, “If the casinos are outside the United States, there’s not a thing we can do about it except prevail upon the host government.”

The WSEX founders had zero moral hang-ups about their exchange. As Cohen told SI in 1998, “You can’t tell me that when someone buys a stock on a Monday and sells it on a Tuesday, that’s investing. That’s gambling. Just like our sports futures market. Internet gambling is the same as my last career, except the folks I work with now are less sleazy.” All three founders were fond of this company line: “If you go to our website and you change Boston Red Sox to Boston Market, we’re Ameritrade.”

World Sports Exchange set up an unprepossessing headquarters above a camera store in a local strip mall and worked to improve its technology. In November 1996, the site officially launched with, Cohen says, a grand total of roughly 20 customers. At a time when people were still setting up email accounts, the trio spent as much time performing tech support as taking bets. “People would call and say they wanted to bet with us,” recalls Ware, now 48. “We’d have to say, ‘We can’t do it over the phone. You have to go down to RadioShack and buy this thing.’”

But bettors got increasingly comfortable online, and, in a late-’90s kind of way, World Sports Exchange went viral. By ’98, there were 2,000 customers. By ’99, that number had tripled. WSEX began advertising in U.S. publications, on websites and on the radio.

It offered two advantages over the competition. More interested in cultivating repeat customers than in booking profits, WSEX found favor with gamblers through its customer service. Cohen, Schillinger and Ware were known to pick up the phone and walk clients through the site, even advising them on whether to hedge on a bet or cash out.

In a sea of bad actors and sites with janky technology, WSEX was regarded as an island of integrity. Gamblers knew that at WSEX, they could post bets a few minutes before kickoff or tip-off or tee-off without worrying about delays. Winners were paid promptly.

But even more critically, as the founders had always envisioned, in addition to betting against a set line or a point spread, they seized on a novel idea. Gamblers could wager throughout the game. They called it “live betting”—first-generation microbetting or in-game betting.

“People couldn’t believe it, and you had to educate them,” says Cohen. “But it was gigantic for us. You mean I can bet on whether Jerry Rice will score the next touchdown or whether the next at bat will be a single, double, triple or home run?”

Cohen says the staff would scramble to set the live odds by hand. Initial bets were usually $50 or $100, and the house vig was effectively 5%. WSEX processed payments through credit cards, PayPal, Neteller and Western Union.

Ware recalls that at one point Western Union flew executives down to Antigua. As a top figure at one of the island’s largest employers, he was invited to the meeting. “They said, ‘We noticed that Antigua ranks third [for volume] on our list of countries, just above Germany. And, uh, we were kind of wondering what’s going on down here.’ And so we had to explain [our business] to them.”

Bookmaking on everything from who would get booted off Big Brother, to the hole-by-hole action in PGA tournaments, to the 2000 presidential election, WSEX was, according to Ware, taking in $1 billion in bets annually and had more than 100 employees. Independently, both Cohen and Ware say the company was on its way to becoming a multibillion-dollar business.

For decades, the NFL was well aware that many fans had financial stakes in its games. And that these fans often bet in the shadows, relying on bookies. A former high-ranking NFL executive says that, by the late ’90s, the subject of betting was debated frequently within the league.

He says that while few anticipated that the NFL could actually get a slice of this revenue, a contingent of executives didn’t mind that so many fans had a reason to tune into games even when the outcome was not in doubt.

Another, bigger faction saw gambling—and its unseemly offshoots—as an existential threat to the sport. If the public can’t trust the integrity of the competition, the entire enterprise is doomed. As far back as 1963, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle told SI: “This sport has grown so quickly and gained so much of the approval of the American public that the only way it can be hurt is through gambling.”

Rozelle’s successor, Paul Tagliabue, the commissioner at the time WSEX launched, thought similarly and knew firsthand the stain that could accompany sports gambling. As a basketball player for Georgetown in the early ’60s, Tagliabue faced NYU, whose top players had fixed games. Tagliabue thought recurring scandals in college athletics showed that illegal fixes could destroy the integrity of major sports. (Contacted for this story, Tagliabue confirms this characterization; the NFL declined comment.)

For decades, gambling was taboo. As recently as 20 years ago, the NFL turned down a Super Bowl commercial from the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. Less than 10 years ago, Tony Romo was barred from simply holding a fantasy football convention at a Vegas casino.

When, in the late ’90s, the NFL got wind of WSEX—operating on an island of seven stoplights 450 miles up from Venezuela, taking in millions in online football bets—the league may or may not have glimpsed the future. But, indisputably, it sprang into action.

At the time, the NFL retained two main law firms: Debevoise & Plimpton in New York and Covington & Burling, the former firm of Tagliabue, in Washington, D.C. These weren’t simply high-powered law firms, they were—and are—revolving doors to the halls of power in U.S. government.

Covington has as much renown for its lobbying practice as for its law practice. As for Debevoise, dozens of the firm’s lawyers had served as U.S. attorneys in the Southern District of New York.

In the spring of 1997, acting on behalf of the NFL, Debevoise hired a private investigator to probe the company. The firm also sent lawyers to attend an internet gambling law conference where Cohen spoke. And a Debevoise litigation partner, acting on behalf of the firm’s sports league partners, sent a letter to WSEX putting it “on notice that [it was] violating various statutes.”

The letter came with a demand that it “cease the transmission of sports gambling information concerning the NFL, the NBA, the NHL.” WSEX ignored the order, viewing it as saber-rattling. The company did, though, comply with demands to stop using NFL team logos, trademarks and team names. “Honestly,” says Cohen, “the fewer the graphics, the faster the [connection] speed.”

All the while, the NFL was making a bigger move. Working for the league, Debevoise not only urged federal prosecutors to pursue offshore sports operators; it also laid out the architecture of the legal strategy. Before becoming an assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York, Tom Rubin had spent the previous four years working as a Debevoise lawyer. In documents and letters obtained by SI, dated from May 1997 through February ’98, Rubin’s former colleagues at the firm encouraged him to bring a case against WSEX and other offshore operators.

The basis for the case: the Federal Wire Act, a law drafted in 1961 prohibiting the use of telephone wires in interstate or foreign commerce for purposes of gambling.

The NFL also had an ally in the U.S. Senate. A former high-ranking league executive tells SI that the league had “significant ties” to Jon Kyl, a Republican from Arizona who took office in 1995, a year before the NFL held its first Super Bowl in his state. During his first term, Kyl took an interest in railing against online gambling, reciting a series of clunky catchphrases to underscore the evil of “e-betting”: “Click the mouse and bet the house! ... Use email and go to jail.”

When Kyl introduced the Internet Gambling Prohibition Act—which would make an online bet taker subject to a four-year prison term—WSEX mocked the legislator, setting odds on whether the bill would pass. It would not. But the crusade drew attention to offshore operators, and emboldened Kyl and other colleagues to draft more targeted anti-gambling legislation.

Then, in March 1998, Mary Jo White, chief U.S. attorney for the Southern District, based in Manhattan, acted on the case the NFL’s lawyers at Debevoise not only encouraged her and Rubin to prosecute, but helped build. (“It’s routine for a law firm to bring concerns and provide relevant background information to federal law enforcement for its consideration,” Rubin said in a statement. “As the overwhelming evidence demonstrated, the SDNY internet sports betting cases were thoroughly investigated by the FBI and prosecuted independent of any such information.”)

White’s office charged 21 bet takers—including Cohen, Schillinger and Ware—with violating the federal Wire Act through their involvement in offshore sports betting operations. The DOJ indictment claimed the government conducted a “sting operation” by opening a World Sports Exchange account, transferring money via Western Union, placing a bet using the telephone and internet, and receiving funds from a winning payout.

This drew a laugh within the online gambling world. Operating in the sunlight, where it was licensed and legal, World Sports Exchange happily and openly took bets from anywhere in the world.

The WSEX founders thought little of the warrant, resolute in their belief they were subject to the authorities in Antigua, which had licensed and regulated the company without issues.

The founders made a plan: As the front-facing figure, Cohen would return to the U.S. and let Ware and Schillinger, who were more operational, continue running the business. Cohen would either fight the indictment or call the U.S. government on a bluff. Then he’d come back to Antigua, and they’d all celebrate.

In March 1998, Cohen left for New York, where he turned himself into the FBI and then hired the prominent defense lawyer Benjamin Brafman to represent him. Brafman was coming off a successful defense of notorious Manhattan club promoter Peter Gatien against a series of federal charges. Cohen recalls Brafman assuring him, “The [Gatien] case was a stretch on the part of the federal government. This case is an even greater stretch.”

Good, Cohen said, because he had no intention of pleading guilty. “I told him, ‘Ben, you will not hear the word guilty roll off my tongue. ’Cause I did nothing wrong. I don’t care if they kick it down to a parking ticket.’ I was very explicit about that.”

But after 10 days before a jury in court in February 2000, Cohen became the first person to be convicted on federal charges of running an illegal offshore internet sports gambling operation. He was sentenced to nearly two years in prison. “An internet communication is no different than a telephone call for purposes of liability under the Wire Wager Act,’’ White told reporters following the verdict. None of the other 21 defendants went to trial.

But as internet speeds got ever faster and sports fans grew ever more intoxicated by betting online—especially during games—WSEX’s business continued booming. Cohen may have been convicted, but prosecutors could not simply stop a company in Antigua from operating.

In 2001, it was the subject of a fairly glowing 60 Minutes profile that deemed the company “more reliable than your local bookie and a lot cheaper than flying to Vegas.” In 2003, WSEX was the internet’s most popular and profitable online gambling site.

Fugitives by choice, Ware and Schillinger joked about being trapped in paradise. But it was less than ideal. When Ware’s older brother got married, Haden, fearful of returning to the U.S. and risking arrest, could only listen to the ceremony from Antigua, through a cellphone in the groom’s pocket. Schillinger had moved to the Caribbean with his wife and two children, but his family moved back to the U.S. without him. Eventually, his wife filed for divorce. “We went from having this cool adventure,” Ware says, “to being exiles.”

Meanwhile, Cohen mounted an appeal. His lawyers made the case that the Wire Act, conceived decades before the internet, was never meant to apply to online transactions. Since the WSEX servers were in Antigua, that’s where the bets were being made, and the U.S. was interfering with the rules of a sovereign country. “The internet,” Brafman said, “isn’t owned by anyone.”

Cohen, though, lost his appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case in June 2002, and he began his 18-month stint that October in the minimum-security Nellis Federal Prison Camp, which, ironically, sits amid Nevada scrub 25 miles north of Las Vegas. Nicknamed “The Professor” by other prisoners, Cohen was paid 45 cents an hour for tutoring in algebra and calculus. His incarceration, he says, was uneventful, save the night 60 Minutes reran the segment and other prisoners learned that the business he had cofounded was doing more than $100 million in annual revenue.

After the 60 Minutes piece aired and re-aired, Cohen received fan mail from a viewer. The correspondent urged Cohen to consider a “pregnancy due date betting service,” an idea WSEX rejected out of hand. But the letter writer also had another suggestion: Why not convince the authorities in Antigua to sue the U.S. for violating world trade rules? The argument was fairly simple: The U.S. permitted bets on horse racing to be placed at “off-track” facilities. By permitting horse-racing operations to take bets remotely and not offshore sportsbooks, the U.S. was giving preferential treatment to American businesses over foreign businesses, a violation of WTO rules.

Cohen’s attorney, Mark Mendel, was intrigued. He was no trade lawyer, but he convinced the Antiguan government to let him represent the country on the matter. With WSEX footing the legal fees, Mendel filed the case at the WTO in Geneva and eventually won, in 2005. Cohen, by then on probation in San Francisco, told an NPR reporter, “I was elated. Finally, some vindication … you know, in 50 or maybe even 10 years they’re going to look back at my case and say, ‘We sent a man for prison for that? What? Are we nuts?’”

But the U.S. government wasn’t done. First, it appealed the decision, and a WTO arbitrator let the U.S. off the hook from any meaningful penalty. Then came the real hammer blow. In the fall of 2006, George W. Bush signed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA), the death knell for online poker and offshore sportsbooks. (Then a decade into the job, Kyl was credited with expediting the UIGEA’s passage through the Senate.)

Under UIGEA, strict banking restrictions were imposed on services like Western Union—suddenly, they wouldn’t process transactions between WSEX and its U.S. customers. Same for most credit card companies. Cohen says WSEX had to seek out less reputable payment processors. Terms were often larded with fees. Cohen recalls that a friend suggested they take bets via a newfangled virtual currency called Bitcoin. “We thought it didn’t make sense,” he says. “Looking back, maybe that wouldn’t have been a bad idea.”

Word started circulating among sports gamblers that WSEX didn’t pay off winning bets promptly, and customers were having a hard time getting their money out. The customer loyalty that WSEX had cultivated was fraying. As Cohen says flatly, “We were being driven underground, and our reputation got dinged.” Already devoting so much money to legal fees, WSEX revenues plummeted. By 2010, Antigua revoked the floundering company’s license.

On Friday, April 19, 2013, the WSEX website officially shut down, citing “inadequate capital resources.” That same day, friends of Schillinger stopped by his condo to invite him to a party. Instead, they found his lifeless body on the floor next to a gun and a note stating that he could not live with the shame and guilt of being unable to pay his customers or cover their funds. In Antigua, authorities downplayed Schillinger’s death, referring to it simply as a shooting.

To Cohen, it all felt so screamingly unfair. And he directed most of his anger at the U.S. government. So much so, he not only moved overseas after his probation but renounced his U.S. citizenship. He returned first to Antigua and then landed in Montenegro, where he oversaw a syndicate of online poker players. The business, he says, didn’t thrive. But a colleague introduced Cohen to his future wife.

Even after WSEX shuttered and Schillinger died by suicide, Ware decided to remain a fugitive. He pinballed around the world—Argentina, Germany, Ireland, Montenegro, Brazil—working for various legal gambling businesses and sportsbooks. Finally, in 2016, he returned to the U.S. and pleaded guilty to the more than a decade-old charge.

He was not sentenced to prison and, after serving probation, moved to rural Connecticut, where he lives with his partner—whom he first met when she worked answering phones for WSEX in Antigua. Like Cohen, he has applied for hundreds of jobs. He consults for digital marketing firms but says, “I’m still a [convicted] felon and I still need to check that box.” Even when he applied recently for the local volunteer fire apartment, he was afraid his application would be rejected. “I like my quiet life here and my little house,” he says. “But I came back to the States with nothing and have just been trying to rebuild. We all have to reinvent ourselves.”

Gyneth McAllister, the former overseer of gambling for Antigua, is now based in Washington and consults for Trinidad and Tobago. “The injustice of it—the whole thing was so cruel—still tears me apart every day,” she says, her voice catching. “These guys were thrown under the bus.”

As for other players, Mary Jo White would leave the Southern District, returning to a job at … the law firm of Debevoise & Plimpton. After serving as chair of the SEC under Barack Obama, she again returned to the firm. While, perhaps most notably, she came under fire for representing the Sackler family as it faced lawsuits stemming from the opioid crisis, she has also booked significant business with the NFL, including her investigation from 2022 to ’23 into Dan Snyder, determining that the former Commanders owner withheld revenue from other owners and sexually harassed a former team employee. (White, through her firm, declined comment; Debevoise itself did not respond to questions.)

After leaving the U.S. Senate in 2013, Jon Kyl ended up at … the NFL’s other law firm, Covington & Burling. In ’18, he was appointed to the Senate seat of the late John McCain. But after the term, Kyl returned to Covington, where, according to public filings, he recently earned $1.9 million as a lobbyist. (Now in his 80s, he did not respond to a request for comment.)

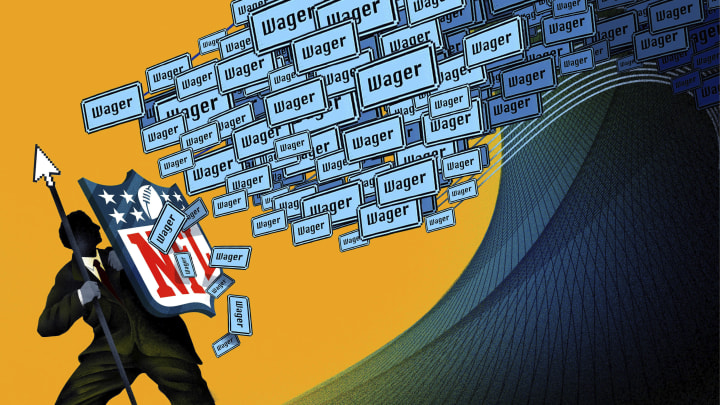

Meanwhile, in the ultimate pivot, the NFL went from branding gambling as an existential threat to embracing it. In 2018, along with the other major sports leagues, the NFL encouraged the Supreme Court to overturn PASPA. Which the court did that year, opening the door for states—38 and counting, plus D.C.—to legalize sports gambling.

Now, of course, wagering is as much a part of the NFL tableau as tailgating. Gambling advertisements are everywhere; team partnerships are common. The same league that not long ago turned down a Super Bowl commercial from Las Vegas tourism is now holding the Super Bowl there.

And the same league whose high-powered law firm helped prepare a federal case against online sportsbooks earned millions last year from online gambling partnerships—not least because of the appeal of the in-game betting introduced on WSEX.

An ocean away, Jay Cohen’s previous life feels immeasurably distant. His Sundays were once devoted to taking bets and setting lines as the company he cofounded took in billions in action. Now he has no interest in football, unable to name the two teams that played in last season’s Super Bowl. The normalization and stigmatization of online sports gambling in the U.S. is vindication that comes seeded with a mix of anger and sadness.

He resists the urge to wonder why, when sports gambling is still illegal in, say, Utah, operators can transmit live betting data directly from Jazz home games without violating the same Wire Act cited in his case. Or why the U.S. government has sided with the Seminole Tribe in its sports wagering dispute, supporting the notion that if the servers handling bets are located on tribal lands, it does not run afoul of the federal statute and a recent Florida state constitutional amendment restricting casino gambling.

Nor does he think about how much WSEX, as first mover, might be worth, given the market cap for DraftKings is more than $30 billion. Or what his life might look like had the NFL not flexed its muscle.

Thousands of miles from the NFL’s Manhattan offices but in a voice still redolent of Long Island, he says: “It’s like, You crushed my business AND stole my idea. Please do one or the other. You shouldn’t do both. It’s like the game was rigged against us.”

Jon Wertheim is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated and has been part of the full-time SI writing staff since 1997, largely focusing on the tennis beat , sports business and social issues, and enterprise journalism. In addition to his work at SI, he is a correspondent for "60 Minutes" and a commentator for The Tennis Channel. He has authored 11 books and has been honored with two Emmys, numerous writing and investigative journalism awards, and the Eugene Scott Award from the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Wertheim is a longtime member of the New York Bar Association (retired), the International Tennis Writers Association and the Writers Guild of America. He has a bachelor's in history from Yale University and received a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He resides in New York City with his wife, who is a divorce mediator and adjunct law professor. They have two children.

Follow jon_wertheim