Ryan Garcia Is Ready to Put His Tumultuous Past Behind Him With Mario Barrios Fight

CALABASAS, Calif. — In January, Joe Goossen sat on a stage looking bewildered. Goossen, the longtime boxing trainer, knew the press conference to announce Mario Barrios’s welterweight title defense against Ryan Garcia could be awkward. A few years ago Goossen was on Garcia’s side of the dais. Now he was training Barrios to beat him. There could be some ribbing, Goossen reasoned. What he didn’t expect was Garcia spending most of the hourlong presser attacking him. He called Goossen a traitor, while suggesting that Goossen may have leaked sensitive information before his 2023 fight with Gervonta Davis. When the event finished, Goossen walked over to me and asked, “What was that?”

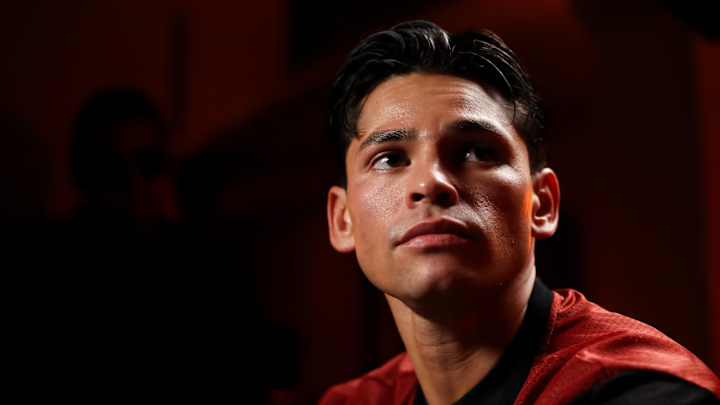

Weeks later, Garcia grins at the memory. “I know who Joe is and he knows who I am,” says Garcia. “And that’s why I knew that was going to fuck with him.” It’s mid-February and Garcia is sitting on a training table inside Craft Boxing Club, a windowless gym tucked inside an office park. He has just finished sparring, which comes with the obligation of snapping a few photos with his opponents. A line of them waited for Garcia as he climbed out of the ring. Garcia’s loss to Rolando Romero last spring may have halted his ascent to the top of the 147-pound division. But it has done little to diminish his star power.

Then again, Garcia has always been a star. He was Instagram famous before he became boxing famous, racking up likes and views even before the wins and knockouts. That fan base followed him. He packed 10,000 into an arena in Anaheim in 2020. He drew more than 6,000 during a pandemic win over Luke Campbell in ’21. In his first pay-per-view, against Gervonta Davis, he helped generate more than one million pay-per-view buys.

Even after the loss to Davis, his ascent felt inevitable. In 2024, Garcia faced Devin Haney. He knocked Haney down three times en route to a decision. But he missed weight by more than three pounds for the fight. In the aftermath, Garcia tested positive for Ostarine, a banned substance. The fight was overturned to a no-contest, while the New York State Athletic Commission slapped Garcia with a one-year suspension.

In the months after, Garcia unraveled. He used racial slurs to attack Blacks and Muslims on social media. He was arrested for trashing a hotel room in Beverly Hills. His social media posts grew more and more bizarre. His own promoter, Oscar De La Hoya, declared him bipolar.

Asked about that period, Garcia winces. He points to alcohol as a major issue. He drank during his training camp for the Haney fight. “I would train hard as shit and then at night I would have a little bit of tequila,” says Garcia. After that, it got worse. He drank during the day. He drank at night. Eventually, he picked up mushrooms.

“But I felt still unstoppable,” says Garcia. “I didn’t feel any badness.”

Last spring, with his suspension lifted, he was offered a fight against Rolando Romero. The purse was substantial: $5 million, according to Garcia. He would headline a unique event in Times Square. Romero was a world champion at 147-pounds, but he was considered one of the weakest ones. When the fight was announced, Garcia was favored 6 ½ to 1.

But he didn’t feel like a favorite. When he started training, his body didn’t respond. The drinking had made him heavy. According to Garcia, to make weight for the fight, he had to lose 35 pounds in two months. “I had a lot of fat on me, from drinking a lot,” says Garcia. “I couldn’t get that out of my body.”

Mentally he wasn’t right, either. “My body was just not ready to go into a camp,” says Garcia. “It needed to take a break from all the things I did. My brain needed to heal, inflammation needed to go down. My body was just not primed to do anything. My body probably thought it actually retired.”

Weeks before the fight, he looked at his longtime manager, Lupe Valencia, and asked him to cancel it. Valencia actually called Golden Boy Promotions president Eric Gomez, Garcia says. At the last minute, Garcia told him to hang up.

Why? “The money,” says Garcia. He forfeited $1.2 million in a settlement with New York after the Haney fight. Prime, the drink company co-founded by Logan Paul and YouTuber KSI, sued Garcia for defamation after Garcia posted on social media that drinking Prime was dangerous for children. He says he owed RIZIN, a Japanese promoter, $2 million after canceling a scheduled exhibition against Rukiya Anpo.

“I was spending so much money on stupid s---,” says Garcia. “Everybody was like, ‘Bro, you just fight. [Romero] is easy.’ So everybody’s in my ear and I really should have just said, ‘No, I got to trust my instincts, trust God will get me through.’ I should have said, ‘F--- it. Let them sue me, I don’t give a f---.’ I should have just done that. But instead I went the stupid route. That was a bad decision.”

Three weeks before the fight he told people in his inner circle: I’m going to lose. The Haney camp, when he drank and smoked and did God knows what, created a belief that he could fight through anything. As he trained for Romero, he realized he could not.

“I still don’t know to this day how I was able to pull that off,” says Garcia. “You know what I mean? But you can’t reenact that, you can’t do that again. That’s impossible. I don’t think anybody in the history of boxing could ever do that again. That’s a one-time thing, never will it be replicated.”

Against Romero, Garcia’s body malfunctioned. His mind wanted to do certain things. His body wouldn’t respond. His trainer, Derrick James, urged Garcia to do things. Garcia could not. Romero knocked Garcia down in the second round and cruised to a unanimous decision.

After the fight, Garcia broke down. “I couldn’t stop crying,” Garcia says. He knew he had the talent but, he says, “I was just throwing it away.” Losing like that was humbling for him. And educational. Among the lessons he took away was that the beating he was putting on his body had to stop. “Man, your body’s a temple,” says Garcia. “And you treated it like shit and this is what you get.”

For Barrios, Garcia has gone back to his roots. His father, Henry, has been a mainstay in his corner since his amateur days. He was the head trainer for Garcia’s first 15 professional fights and even as Garcia has ping-ponged between different trainers—from James to Goossen to Eddy Reynoso—Henry has been alongside. For this fight, Garcis has elevated Henry back to the lead role.

“I think for the [Romero] fight, I didn’t trust my heart and my instincts, and I more so trusted normal, logical decisions,” says Garcia. “So this time around I’m like, ‘O.K., you can’t do nothing about that. That’s in the past, what can they do now? Trust your instincts, get your body right and let’s see what happens.’

“And that’s how I made my decision with my dad. I’m going to bring back my dad because I want to win my first world title for my dad. I feel like he deserves it. He’s been through every camp with Eddy, every camp with Joe, every camp with Derrick, so he’s the guy. Of course, I feel like all my trainers, I will give them some credit, but my main credit will be to my dad. And that’s why I dedicated this fight and the championship to my dad.”

A win—and a title—would mean a lot to Garcia. It would restore him to the ranks of boxing’s best and set him up for some highly lucrative fights. A rematch with Haney is big. As is a showdown with Conor Benn. And Garcia still pines for a rematch with Davis.

A loss, though, would be catastrophic. Garcia doesn’t downplay its significance. “This fight is do-or-die,” he says. Critics, like Haney, have decried Garcia as a cheater. Other fighters and former fighters have, too. Garcia is enrolled in advanced drug testing protocols for this fight. A win would help clean up his image. A loss, especially one that looks like the Romero one, would further diminish it.

That won’t happen, insists Garcia. He says how he treats his body is completely different from how he used to. He doesn’t drink, he watches what he eats, monitoring the amount of sugar he takes in. He does physical therapy, focuses on recovery and says that mentally he is in a great place.

The pressure, he says, feels familiar. When Garcia was 8 years old, he lost his first two fights. He told his father: If I lose the third, I quit. Against an older, more experienced opponent, Garcia won. “It was the fight of the night,” Garcia recalls. “This feels like that moment. I don’t know when I’m ever going to get a chance like this again.”

More Boxing on Sports Illustrated

Chris Mannix is a senior writer at Sports Illustrated covering the NBA and boxing beats. He joined the SI staff in 2003 following his graduation from Boston College. Mannix is the host of SI's "Open Floor" podcast and serves as a ringside analyst and reporter for DAZN Boxing. He is also a frequent contributor to NBC Sports Boston as an NBA analyst. A nominee for National Sportswriter of the Year in 2022, Mannix has won writing awards from the Boxing Writers Association of America and the Pro Basketball Writers Association, and is a longtime member of both organizations.