Max Lenox's amazing journey to much-admired Army hoops captain

This story appears in the Nov. 10, 2014, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Here is a nightmare. On Feb. 12, 1992, at 2:34 a.m., a boy was born in a Philadelphia hospital. The mother, 25 years old and with five children already, had been an alcoholic since she was 14; during this pregnancy she had spent most of her welfare checks on crack. Hospital staffers assumed the worst: that the pus oozing from the newborn’s eyes indicated chlamydia, that the tenseness in his body was a sign of withdrawal. It was no shock when tests confirmed his exposure to cocaine.

Two of his brothers would never see 30. When the boy was seven, his mother would die in a house fire set by her oldest son, then 16, who crashed through a second-story window to escape. Within minutes witnesses would hear the woman screaming as the flames closed in.

She was not a good mother. Let us say that. But she gave this baby a chance -- albeit slim -- when she put him up for adoption the day after his birth. Black skin and drug exposure are disqualifying traits for many adults looking to adopt. Which is to say that no one was clucking over this baby and predicting West Point. No one was pegging him as a future captain of Army’s basketball team. No one was asserting, as his military high school coach does now, “He’s got the stuff to be a general.”

Still, the infant who would come to be called Max Lenox had a few advantages. At seven-plus pounds and 21 inches, he possessed a puzzling robustness for what was then called a “crack baby.” And not only was there a couple desperate to adopt him, but the prospective parents were also financially stable, devoted to each other and determined to give the boy a safe and loving home. From the perspective of the unwanted, this was winning the lottery.

For the couple, though, the baby was a dice hurl for which even the most sympathetic soul had little hope. “I figured he’d be learning-disabled and they’d struggle with him,” says Sandy Deutsch, the North Carolina social worker who conducted the home study for that adoption and learned of Max’s achievements only recently. “Now he’s at West Point?” she said. “Oh, my God. That almost makes me choke up. My God. That is beyond ...” It took a bit for her to gather herself.

Here is a triumph. Yes, Max Lenox is a senior at the U.S. Military Academy. But wait: His path there has not been storybook pat. Lenox will be the first to tell you he is no genius. He flunked two classes as a freshman and almost got kicked out; like Gen. George Patton, Lenox is a “turnback,” a cadet forced to repeat his plebe year and to graduate late. Last year, in a class of 1,084, he was ranked No. 903.

As for basketball, he and Army coach Zach Spiker butted heads until reaching a kind of détente. After a Patriot League all-rookie campaign in which Lenox scored perhaps the most dramatic basket in the history of the Army-Navy rivalry, he spent two years watching his playing time shrink. This year he figures to log far more minutes as the backup point guard, but that’s hardly how he envisioned his final season. “If I play how I’m capable,” Lenox still says, “I don’t think there’s anyone better than me.”

Isaiah Austin daring to dream again after NBA hopes dashed

Yet even after such diminishment, even on a campus filled with former all-staters and future Rhodes scholars, the 6-foot, 200‑pound Lenox inspires a kind of awe. His teammates describe him as “rare” and “very special.” Even though he averaged only 6.0 minutes last season and appeared in just a third of the Black Knights’ games, he was reelected captain. The academy’s sole stated mission is to make each cadet a “leader of character.” Nobody on that stony promontory above the Hudson River is granted authority lightly. “I’ll be lucky if I do half the stuff Max does, become half the leader he is,” says sophomore forward Tanner Omlid. “I want to be like him.”

This is not just a West Point thing. “I still look up to Max,” says American University guard John Schoof, a former high school teammate of Lenox’s. Holy Cross coach Milan Brown, who gave Lenox his first scholarship offer, at Mount St. Mary’s, refers to his “huge, high character. I’m a father of two little girls. Ten, 12 years from now I’m hoping somebody like him walks in my door with my daughter.”

So here is a question: What made that -- him -- happen? Part of the answer, of course, lies in whatever Lenox inherited from the birth mother he never knew. But much is due to a family dynamic that, from the start, made him navigate fault lines of race, sex and religion, upending stereotypes left and right. Much is due to the couple that, three Junes ago, surrendered him to West Point in the brutally efficient exercise known as Reception Day: exactly 90 seconds in the morning to tell your child goodbye; a few hours of dazed wandering on campus as the cadet-candidate gets processed, drilled and shorn; a teary-eyed gathering with all the other parents in an outdoor grandstand for one last look.

At 6 p.m., Max emerged through one of Washington Hall’s sally ports, raggedly marching onto the thick grass of the venerable parade ground, The Plain, with more than 1,200 other plebes, hair tight, uniform just so, his past unknown to everyone but the two white men who could barely glance at each other without losing it.

The band played “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” The men tried to find their son’s face in the crowd. He stepped closer. They thought of their dead parents and their families, all bitterness gone. Then Dave Lenox turned to his husband, Nathan Merrells, to ask a bigger, maybe easier question, the same one that Americans awash in the most startlingly swift social change in the nation’s history have been asking ever since.

“How did we,” Dave said, “end up here?”

*****

One Saturday in the spring of his plebe year, after surviving all manner of trials, Max Lenox hit a tattoo parlor across from Madison Square Garden and had a quotation, in cursive, inked over his heart. Nathan had sent it to him the year before, when Max was at Fork Union (Va.) Military Academy and feeling alone and anything but successful. Max read the words each morning before leaving his room. He can recite them without pause:

All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was

vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible.

That the words were written by a white Welshman, the egomaniacal military genius T.E. Lawrence, mattered not at all. If anything, they were a reminder that Max had known such a dangerous man all his life. Dave Lenox’s dream was far smaller than conquering the Turks, but that didn’t make it any less powerful, or acting on it less bruising. People did get hurt. But Max was the dream, and Dave made him come true.

Today Dave, 56, is president and CEO of the Special Olympics in the state of Washington. He’s one of those people who never take no for an answer, who face down surly waiters or a cancer diagnosis with equal aplomb. In the end, as Nathan says, “he always gets what he wants.”

And what Dave wanted, since he was 10, was a picture-perfect home. He’d had that in Kansas City, Mo.: two older brothers, a father who worked as a railroad switchman, a housewife mom. Some ugly seeds had been dropped into Dave’s consciousness -- all of his grandparents hailed from Barry County, Mo., deep in the Ozarks, where blacks found in the county after sundown risked a lynching, and his father refused to drive through certain parts of Kansas City because he could, as he put it, “smell the black.” But to young Dave he was a hero.

Then everything changed. Dave’s father died of lung cancer, his brothers grew up and moved on and his mother took the dicey job of IRS auditor, packing a pistol and drawing the curtains just in case. As a teenager Dave hustled to keep a sense of domesticity: He made sure his mom showed up for school events. He cooked dinner each night and set the table “so it would be,” he says, “this typical family thing.”

Dave wanted kids, soccer practices, homework hassles. Perhaps it’s hard to imagine now, when same-sex marriage is legal in 32 states and Modern Family has mainstreamed gay fatherhood, but back then there was only one way to achieve all that. And when, after a failed marriage to a woman, Dave accepted at 26 that he preferred men, he figured his shot at “typical” was gone. “When you realize you’re gay, you have to put that all away,” he says. “Everything’s been blown out of the water. It’s, I have no bearings now.”

It took a year for his depression to lift. In 1987, after Dave moved to Parkersburg, W.Va., to run Special Olympics in the state, he met Nathan, an ad designer. They fell for each other instantly, but “we were both determined to do it the right way, the slow way -- as a dating relationship,” Nathan says. “We would follow, sort of, the ‘straight’ rules.”

Both were churchgoers, but Nathan’s fundamentalist Baptist faith was a straitjacket. His parents, Harold and Midge, raised him and two siblings not far from Parkersburg in the tiny village of Little Hocking, Ohio: church three times a week, nightly if there was a revival. Homosexuality was an abomination. Dad was a mailman; Mom, a Sunday school teacher. “I didn’t know any black people,” Nathan says.

Dave and Nathan’s plan to take it slow fell apart when Dave, cutting Nathan’s grass, slipped and sliced off two toes in the lawnmower. Dave needed to keep the leg elevated and couldn’t drive; Nathan invited him to move in. Nathan’s parents figured Dave was just a roommate. They didn’t blink when, in 1989, Nathan gave up a great job to move when Dave took over the North Carolina Special Olympics chapter in Raleigh.

The dominant force in Tar Heel politics then was Jesse Helms, the arch-conservative U.S. senator who famously described gays as “weak, morally sick wretches.” Sodomy was against the law. Until Dave and Nathan met a lesbian couple who had adopted through Lutheran Family Services, they weren’t even thinking about becoming parents. Then, Dave says, “I was, like, This is completely doable. Game on.”

In the summer of 1991, having learned that he had to approach adoption as a single man, Dave contacted Joyce Gourley, director of adoptions for LFS in the Carolinas. LFS founder Bill Brittain had dedicated himself -- at times to the chagrin of the Lutherans’ traditional wing -- to placing children in stable homes wherever they could be found. Gourley took Dave’s paperwork. For the next two months he heard nothing.

As prospective adopters, single men were then considered too undependable, too lacking in “maternal instinct.” But no one was more suspect than gay men; they were often equated with pedophiles or imagined to be trying to “recruit” children. There seemed to be no precedent for a single gay man -- and certainly not a male couple -- adopting in North Carolina. With each passing week Dave assumed the worst. Finally, fed up and fortified by a few glasses of wine, he called Gourley one weekend and left a blistering message.

“I perceive that the problem may be that you think that I’m gay, and here’s the deal: I am,” Dave said. “But we’ve decided that there’s going to be a child in our family, and I just want to know whether you’re a part of that process. If not? Let’s just move on.”

First thing Monday morning, the phone rang. The home study would begin immediately, Gourley said. A social worker would be calling. Dave had to ask: Why the change? “We were waiting for you to come out of the closet,” Gourley said. “We can’t place a child in a home where the parents are afraid. Trying to hide your sexuality won’t work. It’s hard enough to raise kids under the best of circumstances.”

*****

Marginals, outcasts: Really, they were made for each other. By the early 1990s AIDS had devastated and further stigmatized the gay community. Meanwhile, an avalanche of cheap, high-octane, smokable cocaine had ravaged black urban centers, tripping alarms about what Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer called a “bio-underclass” of crack-exposed infants facing “a life of certain suffering, of probable deviance, of permanent inferiority.” Boston University president John Silber speculated that “crack babies” wouldn’t develop “consciousness of God,” and experts predicted a crime wave when such “super-predators” came of age.

Dave and Nathan checked off the boxes anyway: Yes, they’d take a baby of any race, and yes, one exposed to drugs in utero. They did draw the line at a child already displaying symptoms of addiction or impairment. They wanted the hope, at least, that things might turn out O.K.

[pagebreak]

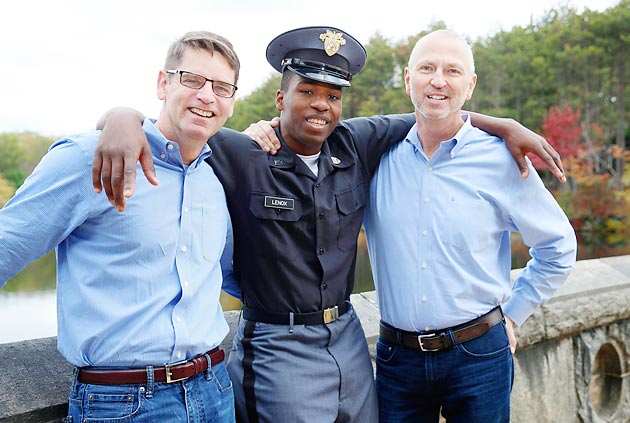

Max Lenox says he was never prouder than the day Dave (left) and Nathan (right) were married.

Victoria Will/SI

Technically Dave applied as a single parent, but from the start LFS evaluated him and Nathan as a couple. “I had to make sure that Nathan and Dave were in it for the long term,” Deutsch says. “But you could tell they wanted to do what was necessary, and it wasn’t about enhancing their lives. It was about making a home for a kid.”

When the call came, on Feb. 13, 1992, from a Philadelphia agency charged with finding healthy children for single adoptive parents, Dave and Nathan were anything but ready. Nathan had always figured that something would derail Dave’s scheme, and c’est la vie. His relationship with his own father was so strained that he assumed he’d be a horrible dad. Now it was happening. Dave rushed to the airport. Nathan scrambled to get the house ready.

By the time Dave landed in Philly, the birth mother’s case history had been amplified. Dave wasn’t surprised that she admitted crack use, but the agency unloaded more details about Corrine Cottom: alcoholism, a history of mental illness, a half-pack-a-day cigarette habit, and bleeding during her last trimester. Then there was the pus in the baby’s eyes, and a “tox screen” confirming cocaine in his system. “Associated risks,” read the affidavit Dave was handed, could include “delayed development in all areas, learning disabilities, sudden infant death and/or mental retardation.”

Dave called Deutsch in a panic, late on a Monday night. “What’s the first rule you learn?” she said. “Birth mothers will lie.” Deutsch went over Max’s vital measures, his full-term birth. The pus turned out to be conjunctivitis. The tenseness? Who knows? No baby’s perfect. “Go get your son,” she said, “and stop bothering me in the middle of the night.”

Nathan met them at the gate in Raleigh. With Max in a carrier, they peeled off to the side of the jetway and crumpled to the floor. “Here’s our son,” Dave said. Nathan cried, Dave cried too, and the two kneeling white men mashed the black baby between them in a hug. None of the deplaning passengers, it’s safe to say, had seen that before.

After five years in the Navy, Mitch Harris chases his big league dream

It was all new. Dave had been out of the closet for years -- his mother had shrugged, his brothers ranged from wary to hostile -- but at 30, Nathan still hadn’t told his parents. Now he had no choice: They were coming to town. He FedExed a letter to the church camp they were attending in Florida and dropped all three bombs at once: I’m gay, you have a new grandson, he’s black. “We didn’t hear from them for a while,” Nathan says.

His mother was crushed, his father aghast. A couple weeks later they checked into a Raleigh hotel. When Nathan took Max to see his grand-parents, Harold inveighed against Nathan and Dave’s “sin,” and Nathan picked up his son and left.

The birth mother could rescind the adoption anytime until her rights as a parent were officially terminated at a hearing 10 weeks later; whenever the phone rang Dave and Nathan were sure it was Corrine calling to take her son back. A Philadelphia judge removed that threat at 11 a.m. on April 30, but the adoption wouldn’t become official -- complete with the chid’s name change from Corey Mark Cottom to Max Lenox -- until August 1993.

At nine months Max took to his feet; by the end of that day he was running. Nine months later the Philadelphia agency called. Corrine was putting Max’s little brother up for adoption. This time Nathan was the one who pushed for it. “We have to do this,” he said. “I couldn’t look at Max if we had the chance to take his brother and didn’t.” But Corrine changed her mind. In 1995, Dave went back to Philadelphia and returned with Erin, a baby girl, black, from a different birth mother.

Dave and Nathan say they began to notice a pattern: People could be brutal, but then a countervailing wind usually blew. When their Episcopal church in Raleigh refused to baptize Max, another church, Pullen Memorial Baptist, welcomed them. After their effort to join the neighborhood swimming pool was rejected because, they were told, “We define family traditionally,” their neighbors rallied and pressured the community association board. Max, Erin and their two dads squeaked in by one vote.

Nathan wouldn’t give up on his parents. After Dave transferred to the Special Olympics’ international office in Washington, D.C., and the family moved to Fairfax, Va., Nathan loaded the minivan and set off on the seven-hour drive to Belpre, Ohio. “Of course you know Max,” Nathan said, stepping into his parents’ home. “Mom, Dad: This is your granddaughter, Erin.”

His father didn’t say hello. The first words out of Harold’s mouth were, “These children are not our grandchildren.”

It was a gut punch. But before Nathan could sag, his mother spoke. Not once in 36 years had he seen her disagree with her husband. There’d have been hell to pay.

“Well, they may not be yours,” Midge said, “but they’re mine.”

*****

It was strange, really, how the fear just leaked away. The first days and months Dave and Nathan kept an eye out for any effect of Corrine’s drug abuse on Max, but within a year his tensing had stopped. He grew up moving so hard and fast, and he picked up sports -- gymnastics, swimming, soccer, tennis -- so easily. Yes, Max was diagnosed with ADHD, but intelligence tests found him average to above, and besides, half of suburbia seemed to be popping Adderall.

Dave and Nathan settled deep into a leafy Fairfax cul-de-sac, packing lunches, worrying about traffic, teachers and TV, nursing the vague hope that their son wouldn’t turn out gay. “Not that there’s anything wrong with that,” Dave likes to say. But this was the late 1990s: Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was the official military policy, and Dave’s oldest brother had broken off relations with him over what he called Dave’s lifestyle. “From our perspective, [if you were] straight, the world was your oyster,” Dave says.

Since then studies have appeared that challenge the crack-baby myth. It’s not that cocaine use doesn’t damage exposed babies: They display lower birth weight and, later, a smaller caudate nucleus, the brain area that controls executive function, memory and learning. But according to studies by Dr. Hallam Hurt, a professor of pediatrics at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine who followed 219 lower-income kids born at Philadelphia’s Einstein Medical Center between 1989 and ’92 -- when Max was born crosstown -- those traits “have not translated to clinically significant outcomes.”

Half of Hurt’s tested cohort had been exposed to crack in utero, and half had not. By age 19 the two groups displayed no significant difference in IQ, performance on a standardized achievement test, high school graduation rates, or drug-use or arrest rates. Yet by age one, both groups lagged behind nonexposed middle-class kids -- especially in IQ.

“What we’ve found is that poverty poses a greater threat to a child with gestational cocaine exposure than the exposure to cocaine in utero,” Hurt says. “It seems . . . that environment trumps the exposure to cocaine.” Hurt’s study also found that children raised “in an enriched or nurturing home” -- regardless of income -- were more likely to do well than those who were not.

Trials in perseverance: D.J. Fluker goes from homelessness to the NFL

“Crack doesn’t do anything to the fetus,” says Carl Bell, a doctor of psychiatry and public health who has practiced on Chicago’s South Side since the 1970s, “but [it was] the drug that caused the most child-protective issues for children. I’ve never seen heroin addicts -- and for that matter alcoholics -- just flat-out abandon their children. But the crack-cocaine people do.”

Max Lenox, of course, is a sample size of one. He was exposed to crack but immediately moved to a nurturing environment. “He would never have had this life without those two men,” says Deutsch. “If he’d been white, he would’ve had a shot. But as a black kid? With what we think is a drug-addicted mom? He wouldn’t have made it.”

As a boy Max knew few details of his background. He was teased some about his dads, got into a few fights, but, he says, “I was always a pretty happy person. My parents were good to me. I’d see parents fighting when I went to my friends’ houses and think, All these people are getting divorced ... and my house is good. We’re all happy. I never wished for any different. I kind of took pride in that I was different.”

It helped that he was usually the tallest, fastest, best athlete too. At 10, Max was playing local U.S. Tennis Association tournaments against 14-year-olds. But he’d picked up basketball the year before, and soon every other sport fell away. John Schoof, who would be his teammate at W.T. Woodson High, can still see Max in a summer league playoff game, coolly loping upcourt as time expires. “At the buzzer Max hit a pull-up three to tie it,” Schoof says. “We were, like, 10 years old. None of us are shooting threes: I could barely get it to the basket.

“He wasn’t a freak athlete, but he was really quick. He was stronger, and he scored a lot; at the same time, he was one of the best passers. But more than anything, he just wanted to win.”

By 12, Max was refusing to take the Adderall; never found it helped, anyway. He emerged as a rising talent in the D.C. area, an AAU star known for unselfishness and for twists that would soon grow into dreadlocks. Neither Dave nor Nathan had a sports background; one Christmas, Max gave Nathan Basketball for Dummies. And nothing, Dave and Nathan say, taught them how not to parent more than the rabid, backbiting AAU scene. Of course, few AAU parents had seen a family like theirs, either. Double takes, puzzled looks -- Max’s teammates loved to see the nickel drop. Black kid, two white men: What the ... ?

When Max was 11, his AAU coach, Rocky Carter, was on the phone with a coaching buddy, a black man, gabbing about Max’s vast potential. He mentioned the two-dad thing, and a moment later he was hearing only silence. “Hello?” Carter said.

“Oh, I’m here,” said his friend coldly, “but I’d rather not talk about it anymore.”

Carter says, “He didn’t approve of that lifestyle and thought Max should be raised by his own race.” The friendship died. “It crushed me,” Carter says.

As it often does, AAU ball brought out the worst in people. After Nathan upbraided an opposing player’s mother for razzing Max’s team mercilessly during a consolation game at the 2006 national tournament in Florida, she told him to get his “faggot ass out of here.” The tiff escalated at game’s end as Nathan and Erin were chased into the parking lot and had to hide in their car. Eventually tempers eased, “but it hurt [Dave and Nathan] and really pissed me off,” Max says. “My parents are my blood.”

Max took Dave and Nathan aside and said, “You know people say that stuff. So what? You know I love you.” He was 14. It wasn’t the last time he would seem to be the oldest soul in the room.

[pagebreak]

Max Lenox is the team's chief motivator, sought out by all players for his advice and encouragement.

Tim Clayton/SI

Playing high school ball was far cozier than AAU. Max and his family felt welcome and protected from the first game of his freshman year, on the road at Oakton, Va. Carter heard some off-color chants about Max’s dads, and the home crowd called Max “Whoopi Goldberg” and taunted, “We smell fresh-man!” the first time he brought up the ball. After he drained a three-pointer, the Woodson fans responded, “He’s our freshman!” That’s how it started: unconditional love.

And why not? Max had already been tabbed as a Maryland prospect in the eighth grade; he was the school’s best player since Tommy Amaker, who would star at Duke. His sophomore season he averaged 14 points and was compared with Villanova sensation Scottie Reynolds. Max was too short and not quite fast enough for Kentucky or North Carolina, but his phone still hummed: Penn State, Minnesota, Boston University, his pick of mid-majors. It was all lining up now: official visits ... D-I ... the NCAAs, and, yeah, no doubt about it, the NBA ...

Then that fantasy died. Bad enough that Max missed the vital AAU showcases before junior year when his left knee required minor surgery. Three weeks before the season opener he was wheeled off the court on a stretcher after he came down from a routine layup, bumped another player and hurt his right knee. Doctors couldn’t tell the extent of the damage until they went in, but Max knew a meniscus tear would end his season. Junior year is the year, recruitingwise. Miss that, and your stock plummets.

Dave and Nathan were there when the anesthesia began to wear off. “It was a tear,” they said, and Max cried until he passed out. When he woke up again minutes later, still foggy, he’d forgotten. He asked again. “It was a tear,” they repeated, and he cried until he passed out. Soon enough he came to. Again he asked. “It was a tear,” they said.

Max didn’t pass out. He did cry, though.

*****

Now came the recalibration. Max played just a few minutes that season, in a playoff game, and the phone calls stopped. He had built his entire self-image around ball. He had been so cocky with the smaller schools -- Yeah, I’ll get back to you -- but now even they went dark on him. “Everything was gone,” he says.

Left alone with his thoughts, he found he couldn’t stand the company. “So what am I? I’m a nobody,” he says. “That year was really rough for me. I did awful in school. I was pretty antisocial.” But even mired in a deep funk, Max absorbed reminders that life wasn’t all about him. In the spring of 2009, Dave was diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer that demanded radical surgery. Driving home from practice one day, Dave told Max about the cancer and asked if he had any worries.

“I want to know what you’re afraid of,” Max said. “Tell me what scares you. That’ll help me.”

Such role reversal was typical: Sometimes Dave and Nathan felt as if Max was raising them. He always gravitated to girls, so his parents’ early concern wasn’t his. And their lifestyle was so buttoned-down, so lacking in rainbow flags and pride parades, so dull, that it seemed as if what the world called gay and what Max lived with were very different things. “I’m as straight as they come, and I don’t like gay people who push it in other people’s faces,” Max says. “It makes my parents look bad. You know your stereo-type gay person who’s flamboyant and wearing pink? The stereotype makes me mad. That’s not who all gay people are.”

Yet when he talks about the summer day that year, on Martha’s Vineyard, when everyone wore white and Dave and Nathan were married on the back porch of their rental house, Max’s voice cracks. “The most pride I’ve had in my family -- ever,” he says, “just knowing that they finally got to do what they’ve been trying to do for a long time, and the world is slowly accepting this great thing that I have in my life. Even though before, I thought, We’re really a family, that was like a message to the world: F--- you, we are a family. And by your standard, too, not just ours.”

It ended up being a good senior year. Dave’s surgery was successful, and Max came back with his best season: 22.8 points per game, 6.1 rebounds, 3.7 assists, 2.5 steals, league player of the year, first-team all-state; he dropped 44 on rival Fairfax High, where his girlfriend was the manager. Senior Night, when the graduating players walk to midcourt with their parents before the game, had been on the family’s mind for years. Nathan had been dreading it, feeling guilty. They had never pushed it in anybody’s face. How would the opposing team’s fans, and the Woodson kids who didn’t know, react? His and Dave’s sexual orientation was their fight, not Max’s. Dave asked his son: Do you want it to be just you and Erin?

Max insisted that all of them go or none. He started crying just before the P.A. announcer called his name. Added to so many other factors -- his comeback, his love for Woodson, the 1,000th career point he had scored a few nights before -- the moment overwhelmed him. Then Nathan took one of Max’s arms and Dave the other, and with Erin alongside they walked into the noise and lights. The crowd stood, cheering, and Max saw friends crying too, and felt his dads’ pride and thought, This is who I am. Like it or not: We’re here.

In truth, he was also on edge. Max still had no idea where -- or even if -- he’d play basketball again. Most mid-major guard slots were filled by the time he proved his knees were solid, and coaches wondered if he’d lost some of his fearlessness, half a step, the potential to compete at the next level. Max had always skated academically, testing well but barely maintaining a C average; now it caught up with him. April came, and schools he would have once dismissed all backed off at the same time.

Max hit rock bottom. A Woodson connection provided an option: Fork Union Military Academy, a Baptist boarding school in rural Virginia. Never mind that coach Fletcher Arritt had spent more than 40 years at FUMA reshaping more than 200 egocentric, unhappy or plain underbaked prospects into Division I freshmen. FUMA prohibited homosexual acts, mandated thrice-weekly chapel attendance and didn’t allow what Arritt calls the Five P’s -- press, parents, posse, perfume (girls) and penguins (bad refs). Cellphones were banned. It seemed the worst match for someone like Max.

When Carter, Max’s AAU coach, called the then 70-year-old Arritt to give him a scouting report, he said, “Coach, I want to be honest with you: He has two dads.”

“What does that mean?” Arritt said.

“They’re gay,” Carter said, thinking, Here it comes.

“I don’t care,” Arritt replied. “Is he a good kid?”

*****

It’s at this point in his story that Max Lenox begins toting up all his second chances. He hated Fork Union’s isolation and strict rules, but the academy taught him organization and time management; for the first time he hauled in straight A’s. And he’d never met a man like Arritt, a coach who cared far more about his players than himself, who could get a bunch of “stars” to ignore personal stats and play for one another, or for him. “He changed my life,” Max says. “There are no other words.”

Half a dozen kids from that FUMA squad went on to play D-I. “One of the best teams we’ve had,” Arritt says. “We were 26–7, and Lenox was responsible for it because he gave the team stability and structure -- and he never let up.” Of course, Max was a prototype Arritt point guard, less athletic than tough and savvy; the time he dived twice on the floor on one defensive possession and bounced the ball out-of-bounds off a beleaguered opponent’s leg, remains “one of the most unbelievable plays I’ve ever seen,” Arritt says.

The coach’s long-standing relationship with Army allowed Max and West Point to get acquainted. Nine other small D-I schools dangled offers in front of Max, but if injury had taught him anything, it was that no conventional basketball program was to be trusted. What if his knee went out again? Army’s new coach, Zach Spiker, sold Max on helping to return the program to the success it enjoyed under Bob Knight and Mike Krzyzewski. Besides, nobody at West Point loses an athletic scholarship. There are none.

Though Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was still in effect, parents are nearly irrelevant at West Point. Spiker visited the Lenox home; he didn’t ask, and nobody told, but all involved figured West Point had never seen a family like this. What of it? Spiker needed a point guard. Max was gung ho. The media guide that appeared just after the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell listed Max’s parents as “Nathan Merrells and Dave Lenox.” No one seemed to notice.

It was just as well. His first semester, Max opened the season a starter, shed the discipline he’d learned at FUMA, failed English and math and earned a D in psychology. After Christmas break an academic board told him he’d have to repeat the failed classes and push back graduation a year.

“He got hit over the head with a two-by-four,” Spiker says.

“I was pretty grateful,” Lenox says. “Not everyone gets a lot of second chances.”

“Then,” Spiker says, “I hit him over the head.”

With the team 5–7 and Lenox’s mind still on his academic peril, Spiker pulled him from the starting lineup. Despite that, Lenox threw up the spinning last-second layup in February that sent the home game against Navy into double overtime and an eventual Army victory. He still tallied the most assists by an Army freshman in 11 years and was named to the Patriot League all-rookie team. He didn’t know, however, that Spiker had stockpiled several hungry guards at West Point’s prep school.

[pagebreak]

Over the next two years, as the Black Knights put together consecutive 15‑win seasons for the first time in 34 years, Lenox saw his minutes halved, quartered, then nearly eliminated. He considered transferring, but something beyond the prestige of a USMA degree kept him from quitting. He recalibrated again.

“I learned so much about myself that I didn’t see happening anywhere else,” Lenox says. “I learned that I can influence people. I felt like I could change a lot of lives -- without basketball. I could be a leader that soldiers and America need. I looked at my life, at what people said about me and what West Point had taught me, and I thought, This is where I need to be. And if I have to sacrifice basketball for it, so be it.”

The message West Point drills into each future officer is, “Care for your soldiers.” No Black Knight does that more than Lenox. During last season’s worst moments he got his teammates hyped for practice, cajoled and counseled them one by one. During games he would tell the guard who took his job, Dylan Cox, “Our battles in practice are harder than this: I know you can do it! I believe in you!”

“When I’m frustrated on the court, he’s the one I go to,” Cox says.

“Max will ask how your life’s going,” says Tanner Omlid, the sophomore forward. “And he doesn’t ask just, ‘How’s your family?’ He says, ‘How’s your dad, Keith? How’s your mom, Allison?’ Last year when my mom got breast cancer, Max was the only guy I talked to about it. He truly cares about me. He wants what’s best for everyone.”

*****

This fall Max Lenox came back stronger than ever. In his final season, attrition has given him one last basketball shot: He’s expected to log far more minutes as Cox’s backup. But his center of gravity has shifted. That’s what happens to 22-year-old men when all goes right. They grow up.

For most of his life, Lenox kept curiosity about his roots on a back burner. He was content; he didn’t want to hurt his parents. But he always knew he was from Philadelphia and kept an eye on the city, especially after Dave told him he had enough brothers to fill out a starting lineup. The Eagles have always been his team. Five years ago, when Dave drove him into Philly for a game, Max craned his neck and asked, “Where are my brothers?”

Dave and Nathan had talked with Max about his birth mother and siblings only when he asked. He didn’t ask much. That caught up with them a few years ago at Thanksgiving when Carter, who considers the two men his dearest friends, turned to Max and blurted, “You were a crack baby.” The room went church quiet.

“You never told me that,” Max told his dads. Had a shovel been handy, Carter would have dug a hole and jumped in.

“I was kind of pissed that my parents would tell other people before they told me,” Max says.

When a reporter first asked, in August, if Max was interested in contacting his birth mother, he was cool to the idea. But by October he’d warmed some. “I’d be interested to hear what she had to say,” he said. “I wouldn’t have a problem with meeting, but I wasn’t going to go out of my way to find her. How about this? You go and talk to her and then tell me the situation.”

A week later Lenox drove the 21⁄2 hours down from West Point, alone, to watch the Eagles play the Giants. He arrived with plenty of time to kill. “I was driving through all these poorer areas and, I was like, I wonder where I would’ve been?” Lenox says. “I was there all day, just looking. I was still thinking, Do I want to meet her? Or keep moving along in my life?”

At the time no one in the Lenox clan knew that Corrine Cottom had been dead 14 years. Or that Max’s oldest brother, Corry, allegedly threatened his mom with a knife that January day in 2000; that he then lit a couch on fire; that after hurtling out the window he sat on the sidewalk sobbing, “My mom’s dead!”; that he was convicted of third-degree murder and jailed; that he died at 27, soon after his release. Or that, for the last five years of her life, Corrine seemed to have been clean.

“She was good; she was functional,” says Pamela Cottom, Corrine’s oldest sister. “She took care of her kids: They ate, they weren’t starving, they were dressed. They didn’t look like they were lacking anything, like while she was on drugs.”

Pamela wants this to be known too: Her sister wasn’t just a crackhead. “She had a heart. If she had something to give, she gave it.” You can feel a bit of that rising off the adoption questionnaire she filled out in 1992.

“Love sports -- to watch [and] play,” she wrote. “Varsity basketball, like to read ...” Asked if she wanted Max to know anything about her, she wrote, “Always welcome to come here.” Would she want her son to contact her once he became an adult? “Yes -- would like -- definitely.”

*****

Late one October morning, while walking the stone bridge at West Point’s Lusk Reservoir, Dave and Nathan told Max about Corrine’s death. His feelings ran from sadness to relief to loss to closure to a puzzled, flat nothing. He had never known the woman, but West Point had drilled into him that each life is precious -- and now an idea from long ago had died along with her. The surrendered child always wonders: Will I ever meet her, see my face in hers? And what of Max’s brothers? Some of them are still alive, somewhere. Maybe someday. . . . Maybe.

So the fathers watched the news sink in, ready to offer a hug or soft words or anything else Max needed, waiting as long as it took for their son to talk it out, because sometimes waiting -- just being there -- is the whole point. Max appreciated the gesture, that they stood ready even now to save him, but he was hardly surprised. That’s how it has always been. That’s what blood does.