As the Transfer Portal Overflows, the Search for Solutions Is On

Surely, by now, you’ve seen the commercials.

Dr Pepper’s ad campaign seems to run on repeat across ESPN’s many platforms. Set in a fictional college-football-crazed town, residents of Fansville go through life with the sport at the center of their existence.

The town got a new addition last year. Erected in what seems like an abandoned park, the transfer portal appears not as a glorified database filled with transferring players’ names but as a mythical doorway that transports players across space and time. The Fansville portal, like the real one, allows players to pass in and out of the gateway at will.

But imagine if the portal had a locking door.

As National Signing Day arrives with an overflowing portal—there are more transfers than there are open scholarship spots—college leaders are exploring adjustments to the database, such as restricting access to certain times of the year and reducing the ability for a player to transfer a second time as a graduate.

Nearly 1,300 scholarship FBS players have entered the portal since Aug. 1.

Matt Kartozian/USA TODAY Sports

“We’re not doing away with the portal. It’s here to stay,” says Shane Lyons, athletic director at West Virginia and the chair of the Division I Council. “But how do we modify it legally?”

Dubbed by coaches and administrators as college football’s new free agency, the portal has the industry abuzz. Players, now given the freedom to transfer once and play immediately, are flooding into the electronic database, some of whom never find a new destination. Coaches and staff members, more overwhelmed than normal, are in a constant juggling act of retaining their current roster while expanding it with portal players. And administrators are trying to come up with a way to fix it all.

The numbers are escalating at a rate never seen before.

More than 3,400 D-I, D-II and D-III players have entered the transfer portal over the last three months—the most in the four-year history of the database, says Brian Spilbeler, cofounder of Tracking Football, an advanced scouting analysis company that examines players in the portal.

Some 1,300 scholarship FBS players have entered the portal since Aug. 1—an average of 10 per team—and nearly half of them have not yet found a destination, according to numbers released by Rivals.com last week.

Similar data was shared with college leaders during the NCAA convention two weeks ago, where NCAA governance director Susan Peal led a portal presentation showing numbers that stunned many of those present.

“It’s scary and unfortunate,” says Ryan Cassidy, a former Rutgers football player who serves on several NCAA governance committees as an athlete representative. “Some kids are going into the portal, and it’s prosperous. And then there’s the other 40%.”

The data has triggered an examination into potential modifications to the portal. In an attempt to slow attrition and avoid midseason player movement, some have proposed closing the portal for certain periods, similar to professional leagues.

Todd Berry, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association board of trustees, has suggested that the portal be open for a few weeks after the regular season, close again and then reopen for a few more weeks after spring practice is complete.

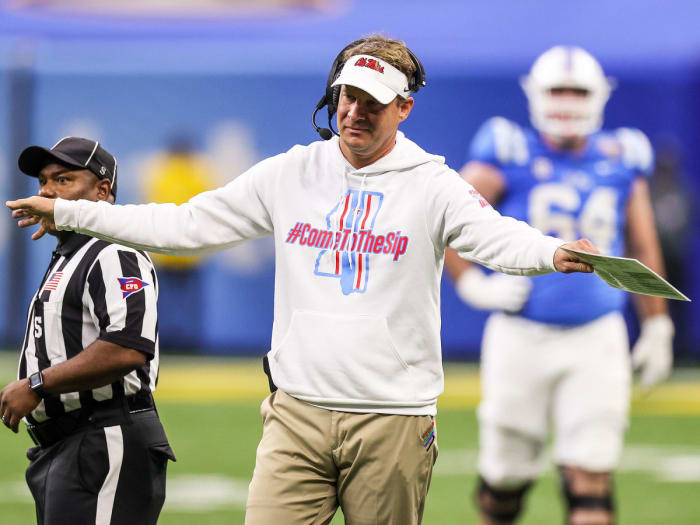

“They’re going to have to do something,” Lane Kiffin told reporters on Tuesday. The third-year Ole Miss coach’s team is among those with the most portal commitments this cycle. “We basically have year-round free agency in football, which is obviously a major issue, which is why they don’t do it in professional sports.”

In such a litigious climate and amid an athletes rights movement in the sport, restricting players’ access to transfer could result in more legal challenges for the NCAA. In fact, in creating the portal, officials previously discussed implementing activity periods but ultimately decided against it for legal concerns. The NCAA’s legal team continues to explore the issue, Lyons says.

Tom Mars, a lawyer who represents coaches and athletes in NCAA cases, doesn’t believe portal windows would limit athletes enough to trigger legal challenges. He says closed and open portal periods are necessary given the transfer data emerging.

“Maybe players aren’t going to like it, but on the surface it sounds like a good idea to me,” Mars says. “If I get any calls from players or parents unhappy that the NCAA has created these windows and they want my help, I’ll tell them to call someone else. I don’t think they would have a leg to stand on.”

Gregg Clifton, an Arizona-based sports lawyer, says portal windows would be “tolerable.”

“You’re not inhibiting them from exercising their legal right,” he says. “You’re creating structure within the transfer process.”

In one proposal, athletes who enter the portal during the open periods will have the opportunity to use their one-time transfer exception and be immediately eligible elsewhere. Those who enter during closed periods will not be eligible immediately.

In theory, this would prevent rash decisions made by young people and avoid midseason departures that impact late-season and bowl games.

“Based on the data I’ve seen, it’s causing a lot of roster management issues and our student-athletes are quitting on their teammates,” Lyons says.

But what about portal windows for other sports? Each sport could make its own decision, Lyons says, or separate windows could be created for spring, fall and winter sports.

Another way to limit transfers is to eliminate the policy allowing a graduating player to transfer again. Right now, a graduating athlete can transfer a second time and play immediately.

Even Cassidy agrees that a “one-time transfer should mean one time,” he says. There is a waiver process for other matters.

Cassidy says the answer is education. Schools around the country are further educating athletes on the risks of leaping into the portal. Some are showing the same data presented last month to college leaders.

“Student-athletes need to see that they don’t need to become just another statistic,” Cassidy says.

This year’s signing day brings with it not only a bevy of high school signatures, but also hundreds of transfer movements.

Roughly 600 FBS transfers have committed to a school this cycle—or about five per team. At least 20 programs have eight or more transfers committed, and teams like USF (14 transfers), USC (13), LSU (12), Nebraska (12) and Ole Miss (11) used more than one-third of their signing spots on transfers. The portal has gained enough traction that 247Sports and Rivals have created separate rankings solely based on a team’s portal commitments, or what one site calls a “portal signing class.” The rankings are based on quantity as well as quality of the transfers.

On Monday, after landing an 11th transfer commit, Ole Miss moved to No. 1, something that provoked Kiffin to post a tweet suggesting he is the “Portal King.” A day later, USC jumped the Rebels for the top spot in 247Sports’s portal rankings after the commitment of ex–Oklahoma quarterback Caleb Williams.

Kiffin's Ole Miss team is among those that have taken the most transfers this cycle.

Stephen Lew/USA TODAY Sports

While meeting with reporters Tuesday, Kiffin discussed what the school referred to as the Rebels’ “transfer class.”

“It’s like talking about a draft class and free agency class in the NFL in the same time frame, which doesn’t happen,” Kiffin said.

Kiffin’s own conference has sent feedback to the NCAA regarding portal windows, SEC commissioner Greg Sankey says. The league feels that a more “orderly process” to the portal would benefit everyone, including the athletes, he adds. He stopped short of revealing whether the league supported such closed and open windows.

The portal created issues for the SEC during bowl time. One team, Texas A&M, pulled out of its bowl in part because of a high number of transfers, and another, LSU, played its bowl despite having fewer than 40 available scholarship players.

“Is there a reasonable way to legally defend a transfer timeline and not create 57 different waiver circumstances?” Sankey asks. “Some say we should wait until the bowl games are complete and then you can transfer. Well, we had a bowl game on Jan. 4.”

If there are restrictive windows for players leaving teams, there must also be restrictive windows for coaches doing the same, says Cassidy. In Peal’s portal presentation at the NCAA convention, she revealed the two biggest reasons that players are transferring: mental health issues and coaching turnover.

FBS saw more head coaching movement than normal this season, with several high-profile coaches leaving blueblood programs. In all, 28 coaches left their school or were fired.

The coaching turnover might not be over. On National Signing Day, ironically enough, Michigan coach Jim Harbaugh was scheduled to interview for the job to coach the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings.

“If coaching is one of the reasons people are transferring and athletes are held to a standard of ‘you can only enter the portal at this time,’ coaches should be held to that standard,” Cassidy says. “Coaches’ contracts should say ‘You can only leave over this period of time.’”

Is that realistic?

“I don’t think it’s realistic at all,” Cassidy replies.

The portal already has naturally occurring windows, says Spilbeler. The height of activity comes after the regular season, mid-November through January, and after spring practice, mid-April through June. While solving some problems, Spilbeler is afraid that restrictive windows will create new issues.

The exploration into the transfer portal is part of a larger holistic evaluation of the recruiting calendar, much of it inspired by the altering landscape in college athletics and all of it interwoven with the NCAA’s ongoing transformation. Officials are seriously examining the early signing period, for instance, with proposals to move it or eliminate it altogether.

“Everything going on with the portal should definitely cause us to look at the recruiting calendar,” he says. “There has been an immense amount of pressure with [support staff] people. It’s been relentless. Something has to happen. There is a huge strain occurring that I don’t think can last.”

Restrictive windows might not tackle the biggest portal issue, some believe. High school recruiting is being adversely impacted as college coaches shift their philosophies. As they use more and more of their precious signing slots on college players, those at the prep level are dropping down the proverbial ladder.

Spilbeler is already noticing a domino effect.

“What I see is that the high school people who might be feeling left out because their spot is taken by a transfer, they still have spots available, but probably not at the level they thought,” he says. “If you’re a Power 5 team, instead of taking a developmental high school player, you decide to fill that with a college player.”

The portal has become such a driving force that college officials this fall increased school signing limits as a way for coaches to replace their players who left for the portal. In theory, they would replace them with more high school players. That’s not necessarily happening.

For Sankey, the portal is the wrong point of focus. “The issue is the deregulation of the transfer space,” he says.

The one-time transfer exception opened the proverbial portal floodgates this summer.

“Let’s remind ourselves of history,” he says. “I’m going to guess you wrote and colleagues wrote [articles] on ‘How can they restrict athletes?!’ And so guess what? We don’t do that anymore.”

So what now? Who knows. But change is inevitable, said Kiffin.

“This transfer thing is not over,” he said. “Until they figure out how to do this better, you’re going to see a whole ’nother group leave after spring ball. It’s year-round free agency.”

More College Football Coverage:

• Riley's Move to USC Already Making Waves in L.A.

• Way-Too-Early Top 25 for 2022 Season

• Tension Looms as CFP Expansion Is Delayed—Again