Revealing My Hypothetical Hall of Fame Ballot

This is the last Five-Tool Newsletter before the results of the BBWAA Hall of Fame election are announced, so I’ll be revealing my hypothetical ballot today. Sure, it has no bearing on the actual process, but it’s fun. And as the lockout drags on, there aren’t too many better things to talk about.

First, here’s a quick refresher on how the Hall of Fame ballot works. BBWAA voting members can select up to 10 players on the ballot. Players must receive votes from 75% of the ballots cast to earn induction, and they must get at least 5% to remain eligible for the following year. They have a maximum of 10 years of eligibility on the writers’ ballot.

This year’s ballot is interesting because there are no slam dunk players on the ballot for the first time. Alex Rodriguez has been suspended for performance-enhancing drugs. David Ortiz is a primary designated hitter who reportedly was one of 104 players who tested positive for PEDs in the 2003 testing of major leaguers that was supposed to be anonymous. Steroid-connected stars Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Sammy Sosa are all in their final year of BBWAA ballot eligibility, as is Curt Schilling, whose abhorrent rhetoric has left many voters to leave him off their ballots. Quite possibly, this could be the second straight year in which the BBWAA elects nobody to the Hall.

Here is my general view of PEDs and the Hall of Fame. No player who is suspended for using a banned substance after the implementation of testing should get inducted. That means no A-Rod and Manny Ramírez this year or in the future, and no Robinson Canó whenever he becomes eligible. I’m more understanding toward players who used PEDs before baseball started testing; although it was cheating, the league did nothing in those days to stop players from juicing. Indeed, MLB was more than willing to enjoy the spoils of the steroid stars for as long as it could. Only when the game’s reputation suffered because of the widespread cheating (leading to a federal investigation) did the league decide to put its foot down.

That said, you won’t find Bonds, Clemens, Sosa or Gary Sheffield on my hypothetical ballot due to the constraints of a 10-player ballot. Voting for them would take a vote away from players who were clean, and we shouldn’t punish them for not cheating. If there was no 10-player limit, I would vote for Bonds, Clemens, Sosa and Sheffield—and I would consider Andy Pettitte.

You also won’t find Schilling on my hypothetical ballot. Schilling is a Hall of Fame pitcher, but I do not want to give a platform to someone who has amplified presidential-election conspiracy theories and defended the Jan. 6 insurrectionists, called for the lynching of journalists, supported anti-transgender legislation, compared Muslims and Dr. Anthony Fauci to Nazis (despite his collection of Nazi memorabilia), etc.

Let's get to the ballot. The first four players were no-brainers.

1. Scott Rolen

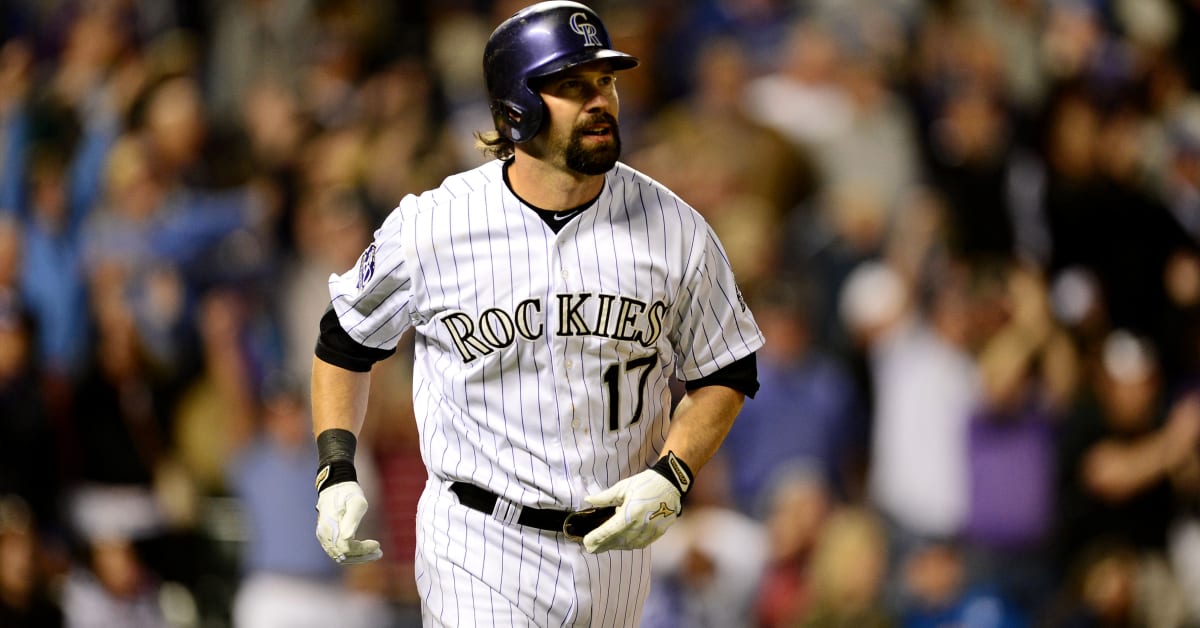

2. Todd Helton

3. Billy Wagner

4. Jeff Kent

Rolen is one of the best third basemen ever, but he is overshadowed by two contemporaries: Chipper Jones and Adrián Beltré. That shouldn’t be held against him. Jones is the best offensive third baseman since Mike Schmidt, and Beltré has the third most WAR (93.5) of any player at the position, behind Schmidt and Eddie Mathews.

As Emma Baccellieri wrote in this morning’s Hall of Fame roundtable: “[Rolen]’s one of the 10 best third basemen ever by defensive WAR. And there's the fact that his offensive power was considerable, too: There have been just 10 third basemen in history (5,000 min. PA) to post a career OPS+ higher than Rolen's. Six are Hall of Famers. (Of the remaining four, two are still active, Josh Donaldson and Manny Machado; the other two are David Wright and Bill Madlock.)”

Helton is one of 22 players in MLB history with a career slashline of at least .300/.400/.500. All but five of the 3/4/5 players are in the Hall of Fame. Two of the five, Joey Votto and Mike Trout are still active; one is Shoeless Joe Jackson, who was banned from baseball because of his involvement in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal; one is Manny Ramírez, who failed multiple PED tests; and one is Helton.

Helton is also one of the best defensive first basemen ever. He ranks eighth all-time in runs from fielding at the position. Some writers don’t vote for him because they consider his numbers inflated due to his playing home games with the altitude advantages at Coors Field. But two things greatly help Helton’s chances: 1) Larry Walker is now in the Hall of Fame despite spending a majority of his career with the Rockies; 2) Research in recent years shows how much of a disadvantage Rockies hitters have when playing on the road. His support is increasing. He’ll eventually get in, and his induction will be long overdue.

No pitcher in league history was better at missing bats than Wagner, who ranks first with a 33.2% strikeout rate and .187 batting average against among pitchers with at least 800 innings. The lack of volume holds him back in the eyes of some voters, but that’s not Wagner’s fault. His job was to get outs over one or two innings, oftentimes in high-leverage situations, and he was as good at that as any pitcher in baseball history not named Mariano Rivera.

Kent has more home runs than any second baseman in MLB history. He was such an offensive force that he could remain at the keystone position despite his so-so defense. As Tom Verducci wrote in today’s roundtable: “[Kent] provided the slugging of a first baseman at second base, which was a huge advantage for his teams. Among all second basemen he not only is first in homers, but also second in slugging, third in RBIs, fifth in doubles and seventh in OPS+.

“Managers could bat Kent cleanup night after night and know he was going to produce runs. Many writers have come to dismiss RBIs, rather than valuing it in context, so they miss much of Kent’s value. Over a 17-year career—nobody’s idea of a small sample—Kent was even better with runners in scoring position (.300/.385/.513) than he was overall (.290/.356/.500).”

The next four:

5. Andruw Jones

6. Bobby Abreu

7. Jimmy Rollins

8. Joe Nathan

Jones is quite possibly the best defensive center fielder of all time. Willie Mays, perhaps his only competition for that, said Jones was a better fielder than he was. Jones also hit 434 career home runs, and for the first decade of his career was one of the most feared sluggers in the game. His sudden, steep decline is what forces me to take a second look before voting for him, but in the end, his dominance from 1997 to 2006 is more than enough for the Hall.

Only six players in baseball history have at least 250 home runs and 400 stolen bases. Three are Hall of Famers—Rickey Henderson, Joe Morgan and Craig Biggio—two are named Bonds, one is Abreu. That’s the stat that most Abreu supporters cite, but by no means is it the only reason to vote for him. He was a model of consistency. Over his best 10-year stretch from 1998 to 2007, he slashed .302/.411/.505 and averaged 22 homers, 29 stolen bases, 157 games played and 5.2 WAR per season. His 60.2 lifetime WAR is 19th among right fielders, just ahead of two of his contemporaries, Ichiro Suzuki and Vladimir Guerrero.

The knock on Abreu is he was never considered the best when he was playing. He made just two All-Star teams and never finished in the top 10 for MVP. He would be far more appreciated if he played today because of his ability to get on base, a skill that wasn’t as widely recognized during his prime. Among players who debuted since integration, Abreu ranks 34th in times on base (3,979), ahead of Hall of Fame outfielders such as Tony Gwynn (3,955), Lou Brock (3,833), Billy Williams (3,799) and Roberto Clemente (3,656)—who all had more plate appearances than Abreu.

I dedicated the Dec. 17 edition of the Five-Tool Newsletter to Jimmy Rollins’s Hall of Fame case, so I’m not going to go too much in depth here. At his best, he was a five-tool player who was the second-best shortstop of his era, behind Derek Jeter. Furthermore, he is the most Hall-worthy shortstop to debut since 1996. As I wrote in the Dec. 17 newsletter: “If Rollins isn’t a Hall of Famer, then who is the next HOF shortstop after Jeter? Carlos Correa? Francisco Lindor? They both still have a lot more to accomplish before we can even consider them. But, let’s assume they do make it. They debuted in 2015, 20 years after Jeter. That would be the longest debut gap ever for HOF shortstops. It also would mean that MLB went two decades without producing a shortstop worthy of induction.”

Two weeks ago, I wrote about Joe Nathan’s Hall of Fame case. For 10 years, he was the best closer in baseball, behind Mariano Rivera. From 2004 to '09, Nathan’s first season as a closer until he missed all of '10 after having Tommy John surgery, he was as good as any reliever in the league.

At some point, the Hall of Fame is going to have to start honoring more closers. It can’t just be the firemen of the 1960s, '70s and '80s, Rivera and Trevor Hoffman. Wagner and Nathan are two of the best one-inning closers to ever pitch. They both belong in the Hall.

And, finally:

9. Tim Hudson

10. Mark Teixeira

These last two spots came down to four players: Tim Hudson, Mark Teixeira, David Ortiz and Mark Buehrle. I would’ve voted for all four if I had enough on the ballot. My exclusion of Ortiz is not because of PEDs. His reported positive test in 2003 is not enough to conclude he was using. Verducci, who is as steadfast in his refusal to vote for steroid users as anyone, summed up Ortiz’s situation better than anyone in this piece from '15. He wrote:

“The greatest knock on Ortiz’s Hall of Fame candidacy is the 2009 report by The New York Times that he appeared on a list seized by government agents said to contain the names of 104 players who tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs during survey testing in '03. In an unprecedented move, the union mounted a public defense on behalf of such a tarnished player—with the backing of MLB. The late Michael Weiner of the union did a superb job explaining why connecting a name on the list to 'tested positive for steroids' was a rather big leap.

The facts as defined by Weiner, which still have not been disputed, are that only 83 of the 104 names on the list were considered to be “confirmed positives.” Why the gap? The number 104 represents positive tests, not individual players, meaning some players on the list tested positive multiple times. “A maximum” of 96 players actually tested positive, with the positive tests of another 13 players not confirmed because the union disputed them. Because of testing protocols at the time, a player could be linked to a positive test while using over-the-counter supplements that did not include banned substances in its ingredients.

(Ortiz has denied using steroids, suggesting his over-the-counter supplements and vitamins could have landed him on the list of 104. This position recalls what recently-minted Hall of Famer Randy Johnson told me years ago when I asked him if he had used banned substances: “I’m not denying that I went to GNC and all that stuff, you know? I took a lot of different things that, you know, maybe at that time, maybe early enough, if I would have been tested, who knows?")

That brings us to another key point: We still don’t know what substance put Ortiz on that list of 104.

So here are the facts as we know them: Ortiz’s name wound up on a list in which one of out every five players on it are not considered to be confirmed positives, and we have no idea what substance—anything from an over-the-counter supplement to hard-core steroid and anything in between—put him on that list in the first place.

Does that put Ortiz above suspicion? No, but suspicion is not enough to damn a career, and, for now, leaves the link between Ortiz and steroids as an interpretive one, not a factual one. The book is not closed; the quest for facts is an ongoing one.”

Instead, the reason I’m omitting Ortiz is because I need space on this ballot. Big Papi is going to get into the Hall either this year or next. Teixeira and Hudson need my support more than he does.

I’m a little surprised to be writing about Hudson, whose numbers at first glance seem to fall below Hall of Fame standards. But he is one of the top starting pitchers in the 75 years since integration. In that span … his 56.5 WAR ranks 42nd, ahead of Hall of Famers Whitey Ford, Sandy Koufax, Jim Kaat, Jack Morris and Catfish Hunter; he ranks 15th in winning percentage (.625), ahead of Greg Maddux, Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson; and 24th in ERA+ (120), ahead of Bert Blyleven, Tom Glavine and Steve Carlton. I do not think he’s a better pitcher than all of these guys he’s ahead of, but he is in pretty great company. Interestingly, his 29.8 win-probability added is 28th best among starters since integration.

Teixeira is one of the best switch hitters in baseball history. He had eight consecutive seasons with at least 30 home runs and 100 RBIs. He was perhaps the most valuable member of the Yankees in 2009, the year they won their most recent World Series. It’s true defense alone shouldn’t get players into Cooperstown, but it should boost the cases of great hitters who were even better defenders. Teixeira’s 88 runs from fielding rank fourth all-time among first basemen. I’m not totally sure he and Hudson belong in the Hall of Fame, but they definitely deserve a longer look.

If you have any other questions or comments for our team, you can send us a note at mlb@si.com.

1. THE OPENER

“They don’t have a clear path to playing time with their current teams, but they still have much to offer clubs that wish to acquire them after the lockout ends.”

That’s the summary for Will Laws’s column from yesterday on the five players who should be traded when the lockout ends. It’s an interesting look at some of the guys who could flourish in another uniform.

You can read Will’s entire piece here.

2. ICYMI

Roundtable: Who Should Make the Hall of Fame? by SI MLB staff

We asked our writers to advocate for one player on this year’s ballot to get elected to Cooperstown.

How Each AL Playoff Team Can Address Its Most Pressing Needs by Nick Selbe

The Astros, Rays, White Sox, Red Sox and Yankees have to shore up these weaknesses to return to the postseason in 2022.

The Most Pressing Needs of 2021’s National League Playoff Teams by Will Laws

Here’s what the Braves, Brewers, Cardinals, Giants and Dodgers need to address when the lockout ends.

MLB Nixes Rays’ Plan for Tampa-Montreal Split Season by Ben Pickman

3. WORTH NOTING from Stephanie Apstein

The premier shortstop remaining on the free-agent market, Carlos Correa, announced Tuesday that he was hiring Scott Boras to represent him. (Boras also represents the other biggest-ticket shortstop from this free-agent class, Corey Seager, who signed a 10-year, $325 million deal with the Rangers before the league imposed a lockout.) Boras is known for negotiating large deals on behalf of his clients, but there could also be another reason for Correa’s switch: His old agency, William Morris Endeavor, is owned by a company that bought nine minor league teams in December. The Players Association sees that as a conflict of interest and is considering imposing discipline on WME, up to and including decertification as an agency.

4. TRIVIA! from Matt Martell

Before we get into this week’s question, here is the answer to the one I asked last Friday.

Last Week’s Question: There are five active players with at least 2,000 career hits. Can you name them?

Answer: Albert Pujols (3,301), Miguel Cabrera (2,987), Robinson Canó (2,624), Yadier Molina (2,112), Joey Votto (2,027)

This Week’s Question: Tim Hudson ranks 15th among starting pitchers in winning percentage since integration (minimum 400 games). The active leader in winning percentage ranks third with a .662 winning percentage. Can you name him?

5. MAILBAG from Emma Baccellieri

Welcome back to another round of the mailbag. Questions for next time? mlb@si.com, or @emmabaccellieri on Twitter.

If a position player makes an error allowing a run to score, the pitcher naturally is charged an unearned run. But if the pitcher makes an error, it's still an unearned run. Never made sense to me. The pitcher caused the run to score. Why is that not an earned run? —Stacey

Oh, I like this one, because it hits on a particular frustration of mine. I can respect the logic that earned runs should be earned only through a pitcher’s pitching ability—any error he makes as a fielder falls outside of that. But if that’s the case … shouldn’t a run from a balk be unearned, too? If the distinction we’re making between “earned” and “unearned” is what happens as a direct consequence of pitching, rather than simply anything done by a pitcher, I think a balk should be treated the same as an error. And because it isn’t, I feel like the framework of the logic here is busted! Alas.

What would an expanded playoffs actually look like? After this wildcard weekend in the NFL, I’m curious. —@2015WSGame3

First: Given the choice, I’d prefer the playoffs stay as they are. But because change seems increasingly likely … I think the league is aware that people don’t want to see the value of the regular season eroded too much, and so any potential structure for expansion will give top teams a first-round bye, the ability to choose their opponents, or some combination of the two. (It’s worth noting that MLB’s reported proposal from November had both of those features—a first-round bye for the top team in each league and the ability for the remaining division winners to pick their opponent.) Is that enough? I’m not sure. But I’m definitely intrigued by the possibility of a pick-your-opponent scenario—it introduces fun strategy without being too gimmicky—and I think it could make the process a bit more exciting.

But I don’t think we’ll see something like what we had in 2020. A 16-team field with no first-round byes made (some) sense for a shortened pandemic season, but it’s just too big and introduces too much randomness going forward. I think it’s much more likely we see expansion to 14 teams, at most, with some kind of mechanism in place to give top teams an easier path through the first round.

What might MLB's version of the NFL's Nickelodeon football game look like? —Ashley

And a natural follow-up to the last question! I’ve loved Nickelodeon's NFL broadcasts and would be extremely into a version for MLB. The biggest must-have is—duh—slime animation for anyone who crosses home plate. Beyond that, I’d like speed effects for any stolen base attempts, booms and pows for replays of guys getting thrown out on the base paths and, of course, tons of animated effects for any bat flip. And I think there could be some additional fun stuff with replays of pitching sequences: flames for fastballs, big bendy loops for curves, some kind of funky animation for changeups. Which is all to say: Please, please, please let this happen.

Why is the foul pole considered in fair territory? —@funwithnumberz

I’ve got to say that this is one I’ve never really thought about before! (Though I do remember wishing for a moving-foul-pole home run controversy during a particularly windy playoff game this year.) But I think I can see the logic that the foul pole is a marker of where foul territory starts, and therefore the territory begins only where the pole ends … which, of course, leads to the question of whether any team has considered the marginal benefit of wider foul poles that could slightly extend fair territory. (A quick glance at the Official Baseball Rules notes that while there is a minimum distance from home plate to each foul pole, there are no specifications about the foul pole itself.) A minor innovation to dream on, I suppose.

That’s all from us today. We’ll be back in your inbox next Friday. In the meantime, share this newsletter with your friends and family, and tell them to sign up at SI.com/newsletters. If you have any questions or comments, shoot us an email at mlb@si.com.