Gap growing ever wider between college sports' haves, have-nots

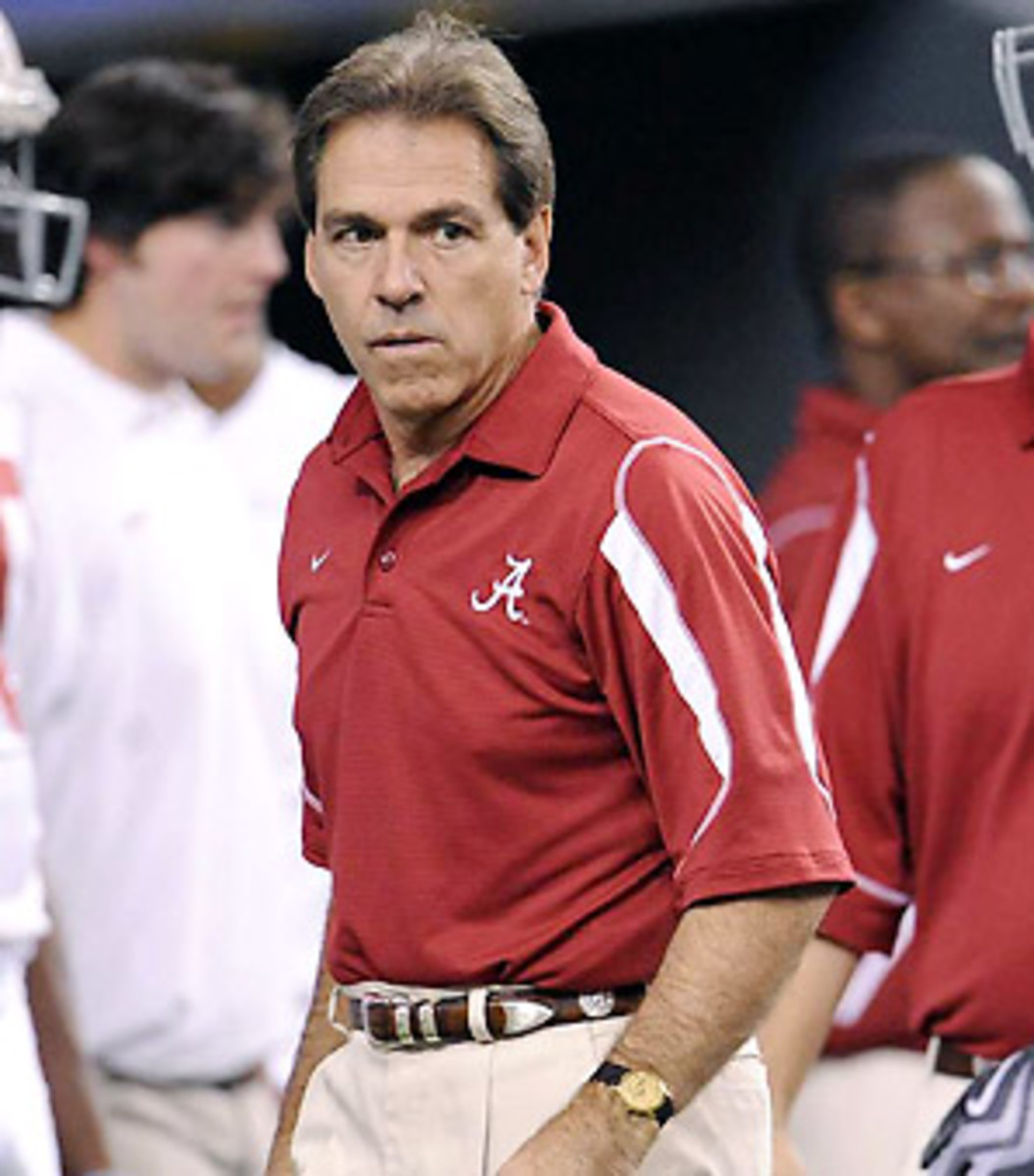

To understand how the recession will affect college sports, scan the headlines. On Monday, Florida coach Urban Meyer agreed to a six-year contract that will pay him $4 million a year. Earlier this year, the Alabama state university system's trustees approved earlier a $80.6 million project that will expand Alabama's Bryant-Denny Stadium to accommodate more than 101,000 fans. Meanwhile, on the other end of the Football Bowl Subdivision food chain, Hawaii athletic director Jim Donovan last week took a voluntary seven percent pay cut to help offset a projected $2.6 million deficit for the 2008-09 fiscal year.

Florida and Alabama, which don't use public money to subsidize athletics, aren't spending foolishly. According to figures filed with the U.S. Department of Education, Florida's football program generated $66.1 million in revenue in the 2007-08 school year. Meanwhile, Alabama has a football season-ticket waiting list of more than 10,000, and football-only revenue topped $57 million for the 2007-08 school year. Meyer's $750,000-a-year raise and Alabama's stadium expansion should more than pay for themselves. The Gators, Crimson Tide and the rest of a handful of almost recession-proof athletic departments should continue to surge forward. Meanwhile, Hawaii and its ilk will struggle mightily.

"The gap is going to continue to get wider between the haves and have-nots," said Dan Fulks, a Transylvania University accounting professor who also studies athletic department spending for the NCAA. "That's kind of a microcosm of society. That's happening to you and me as well."

Facing a recession, college athletic departments generally encounter the same issues as corporations or private citizens. The healthiest ones, the profitable ones who spent money wisely while also accruing a nest egg, can use their increased buying power to take advantage of the down economy. Meanwhile, the ones who already lived month-to-month or year-to-year must take on more debt or slash costs to the bone.

Fulks, who just completed a study of 2008 financial data to update his 2006 study, said 25 of the 120 FBS athletic departments generated more money than they spent. That's up from 19 in 2006, and the median surplus for the departments turning a profit jumped more than $1 million to $3.9 million. Now for the bad news. The other 95 departments ran a median deficit of $9.87 million. For public schools, taxpayer dollars usually cover that deficit. Fulks expects the gulf between the profitable and unprofitable departments to grow more next year because of the recession.

Because Fulks' study guarantees anonymity, he didn't name the profitable schools, but some are easy to guess. Alabama, Florida, Michigan, Ohio State and Texas are examples of programs with huge fan bases and massive revenues. Those programs should be better positioned to withstand a dip in the economy. But being a public university in a power conference doesn't necessarily guarantee financial success.

Last month, The Eagle in College Station, Texas, obtained documents that showed Texas A&M's athletic department took out a $16 million line of credit from the university's general fund in 2005. Beginning this year, the department has 10 years to repay the loan interest-free. Meanwhile, Oregon State athletic director Bob De Carolispainted an unhappy picture in a June 2 letter to fans posted on the athletic department Web site. De Carolis wrote pledges had dropped $1 million from a year earlier to $10 million. Also, the program had suffered a net loss of 600 donors, and 12 percent of football season-ticket holders had not renewed. "When you combine the trends in giving and ticket renewals, the potential for a negative effect on the OSU Athletic Department and our offerings becomes a stark reality," De Carolis wrote. "Because gifts and football tickets make up 40 percent of our annual $47 million athletic department budget, they represent key sources of revenue for us."

Oregon State receives a share of revenue from the Pac-10's television contracts and from bowl money collected by conference members. But even with that, a financial chasm exists between the Beavers and USC, the conference's dominant football program. According to data submitted to the Department of Education, USC had a $76.4 million athletic department budget in 2007-08.

It's even worse outside the BCS. Hawaii's $2.6 million deficit for 2008-09 will be added to the $5.4 million deficit the department carried into the fiscal year. "We've made $1.3 million in cutbacks, we have open positions that aren't being filled," said Donovan told the Honolulu Star-Bulletin last month. "We're doing everything we can do to lower our expenses without doing any long-term damage to the athletic programs."STAPLES: A humble suggetion for mid-majors

When most of their spending is tied up in scholarships and salaries, schools are hard pressed to find ways to minimize the recession's effects. Most programs are loath to cut sports, but some have had no other choice. In April, Cincinnati announced it would phase out financial aid for athletes in men's track and men's swimming. In May, Washington eliminated men's and women's swimming and Arizona State eliminated men's tennis, men's swimming and wrestling. Even Stanford, which just won its 15th consecutive National Association of Collegiate Athletic Directors Cup last week, will eliminate varsity fencing unless athletes can raise $250,000 to pay for the 2009-10 season and then raise enough money to endow the program. Stanford also has cut into its other major budget line: salaries. To help offset a projected $5 million shortfall over three years, Stanford eliminated 21 positions (13 percent of its staff) in February.

Fulks said the highest salaries -- for head football and men's basketball coaches -- won't fall because those rates are market-driven. Unfortunately for the unprofitable programs, the profitable schools usually set the prices and the salary scale trickles down. "If (Kentucky) is paying (basketball coach John) Calipari, then Tennessee has to pay (basketball coach Bruce) Pearl," Fulks said. "That's totally market-driven. The reality is that if you cut the salaries to a couple hundred thousand dollars, they'd still be lining up around the block to get the jobs. But if one school is paying, everybody has to."

While it might be true that Ohio State football coach Jim Tressel or North Carolina basketball coach Roy Williams would work for a low six-figure salary, the NCAA can't cap coaches' income. A reporter asked SEC commissioner Mike Slive about such a salary cap in May. Slive, a former attorney and judge, cracked a smile and said a cap would be great, if only Congress would repeal the Sherman Antitrust Act.

One way to lower coaches' salaries is to furlough them with the rest of the employees at a university. Coaches at Arizona State, Clemson, Maryland and Utah State have all taken furloughs in the past nine months. In the ultra-competitive world of coaching, a furlough is nothing but a salary cut, because most coaches refuse to stop working. At Clemson, football coach Dabo Swinney had to choose five days for which he would not be paid. He wasn't exactly sure which days he chose, but he knows what he did on those days. "What do you mean what did we do? We worked," Swinney said with a laugh. "Are you kidding? We work when we're on vacation."

Swinney said he would never complain about the furlough because he knows how hard a five-day pay cut will hit some fellow university employees. N.C. State athletic director Lee Fowler echoed that sentiment, saying athletic department employees must be sensitive to the trials faced by their counterparts on the university side as state budgets shrink. "We're very much a part of our university," Fowler said. "We've got colleagues who are losing jobs because of the economy. We definitely keep that in mind."

In the FBS, the surest way to bring in money is to sell football tickets. After laying off staff in February, Stanford athletic director Bob Bowlsby admitted as much to the San Francisco Chronicle. "If we could consistently draw bigger crowds, we could solve a lot of our problems," Bowlsby said. In a soft economy, keeping prices flat can help encourage season-ticket renewals. South Florida, Hawaii, Louisville, North Carolina and Wisconsin are among the programs that opted against raising prices this season. The Badgers recently reported a 94 percent renewal rate. That's a drop from 2007 and 2008, but it did fall in line with athletic department officials' budget projections.

South Carolina, meanwhile, had the misfortune of instituting a seat-licensing program last August, a few months before the economy took a nosedive. The change resulted in an 11.4 percent decline in renewals following the second of two May deadlines to renew. Bryan Risner, the head of development for South Carolina's athletic department, told The (Charleston, S.C.) Post and Courier last month officials had built a "10-12 percent attrition rate" into the budget before they instituted the seat-licensing program, so the drop should not affect the Gamecocks' budget.

Fortunately for South Carolina and the other 11 schools in the SEC, the conference's new television contracts with CBS and ESPN/ABC should ease budgeting concerns. The contracts, which begin this year, will net the conference $3 billion over the next 15 years. So when the league divides the profits from TV and bowl revenue next year, each member school should expect an additional $5 million. That's great news for Mississippi State, which must compete against revenue-generating machines such as Alabama, Florida and LSU. "It's certainly going to help us," Bulldogs athletic director Greg Byrne said. "Our salaries are low. Our facilities need work." And the windfall won't only help athletics, Byrne said. It should also allow the athletic department to make a greater contribution to the academic side.

The SEC's agreements were signed before the sharp economic downturn in late 2008, so other conferences looking to emulate those deals may not find the bidding so high. Still, the leaders of other BCS conferences know steady television money provides excellent armor against a recession. ACC commissioner John Swofford, whose conference reaped a TV-revenue windfall in 2004 following expansion, said the league will examine the SEC model (selling rights to a broadcasting company) and the Big Ten model (selling rights and forming a television network to broadcast additional games) as it prepares to negotiate its next network contract, which would begin with the 2011 football season. "Everything is on the table," Swofford said.

The SEC's Slive has repeatedly warned "there is no safe harbor" in a recession, but the SEC and the Big Ten -- with its eponymous television network -- sail in the sturdiest boats. In many cases, programs outside the six BCS automatic qualifying conferences are hoping to take even greater advantage of trickle-down economics. Or, as Fulks calls them, "body-bag games."

While some non-BCS programs have regularly scheduled guarantee games against elite football opponents for a six-figure payday, the recession seems to have changed the dynamics. First, the less wealthy programs have realized they can drive up the price because a home game is so valuable to the wealthier programs. For instance, Georgia will shell out $925,000 to open the 2011 football season against New Mexico State and $975,000 to open the 2013 season against North Texas.

Also, some programs that have avoided such games in recent years now seem more willing to travel for a paycheck rather than for the promise of a home game against that opponent in a future year. In June, Boise State athletic director Gene Bleymaier told the Idaho Statesman he is aggressively pursuing guarantee games. "Right now, I'd go where I can make the most money," Bleymaier told the paper. "If I can play at home and make that much money, then I'm going to play at home. But it's difficult to make that much money in our stadium. ... I've tried to avoid those (guarantee games). Now they're much more of a reality going forward."

Last month, Boise State announced it would play Virginia Tech in Washington in 2010. The Broncos, who have open slots for such games in 2010 and 2011, may face other issues when seeking a guarantee game. The "guarantee" implies a near-certain win for the home team, and Boise State can't offer that. The Broncos are 98-17 since 2000, and their win against Oklahoma in the 2007 Fiesta Bowl is considered one of the greatest upsets in college football history. If potential opponents are looking for a bright side, though, there is one. Since 2000, Boise State is 1-8 in road games against BCS-conference opponents.

The financially healthy departments who could wind up paying for a visit from Boise State's football team have faced a different challenge during the recession, as they must weigh even more carefully the political ramifications of their spending.

For example, Florida's Meyer won his second national title in three seasons in past January, but didn't receive a raise until Aug. 3. In this day and age, athletic departments typically move quickly to financially reward an ultra-successful coach, but the holdup here may have had something to do with the $42 million the school lost in state funding for the upcoming fiscal year that forced layoffs and severe cuts in academic programs. And while Florida's athletic department actually donated $6 million to the university earlier this year, a sizable hike in the football coach's pay (from $3.25 million annually to $4 million in the new six-year deal) may anger some on the academic side.

Florida president Bernie Machen, who asked athletic director Jeremy Foley to hold off on announcing raises for Meyer and basketball coach Billy Donovan when the pair were coming off national titles in 2007, knew Meyer would get that raise sooner rather than later. In fact, Machen made it known he wanted to see Meyer become the SEC's highest paid coach. "He should be," Machen said at the SEC's spring meetings. "He's the best."

Machen, who saw the non-BCS side of the coin while serving as Utah's president from 1997-2003, said the healthy athletic departments can't simply stop spending or trying to improve because doing so might be politically unpopular. That could cost more in the long run, he said. "It's like if you don't fix your roof while it's a patch job, then you're going to replace your whole roof," Machen said. "Most people are understanding that we've got to keep going in athletics."

So until the nation digs itself out of recession, mega-powers such as Florida, Alabama, USC, Notre Dame and Michigan will patch their roofs -- or, in some cases, expand their stadiums -- while programs such as Stanford, Oregon State and Hawaii try to weather the economic storm as best they can.

"Even in the BCS conferences, there's a world of difference between Oregon State and Southern Cal," Fulks said. "Then you get outside the BCS, and those poor schools, they're really getting busted."

MORE COVERAGE:STAPLES: A humble suggestion to help mid-majorsSTAPLES: The impact on high school athletics