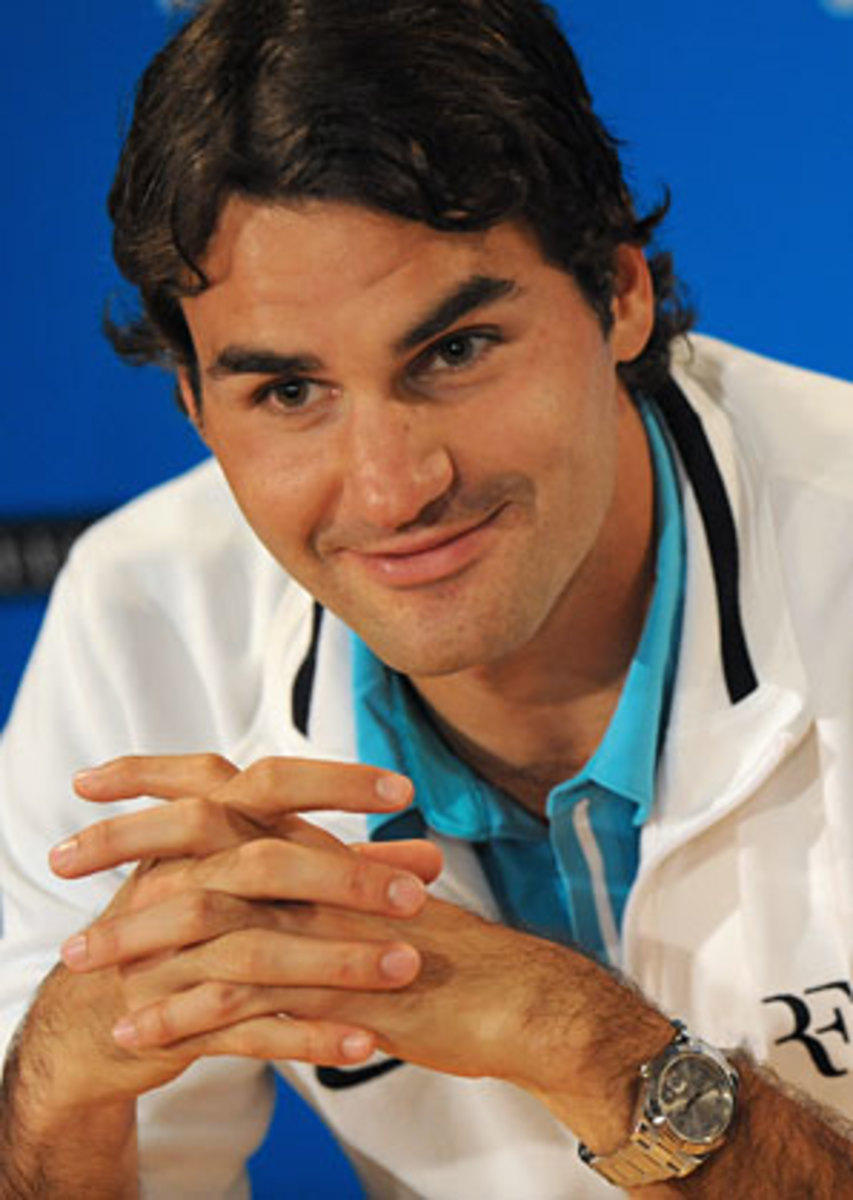

Federer has navigated throwback path to tennis immortality

Roger Federer's path to greatness is a throwback, a reminder of more sensible times in the sport, when players competed well into their 30s without losing their talent or motivation. Ask Rod Laver, Margaret Court or any of the seasoned greats who made their presence felt at the Australian Open; this is how it's supposed to work in tennis. But it seems to leave more contemporary generations in shock.

"I'm flabbergasted to know what still motivates Federer," Pat Cash told reporters in Melbourne. "I certainly couldn't keep it up. There must be a real challenge there. He showed he still has stuff to prove to himself and to match up with the young guys."

Commenting on the Tennis Channel, Justin Gimelstob went so far as to say, "This guy has a pure love of the game that we haven't seen before." Well, no. We've seen it countless times before -- just not lately. The tennis life is so crazy these days, even the indestructible one, Rafael Nadal, appears a bit ghostly.

Make no mistake, Federer is special in ways few can comprehend. He'll own at least 20 majors by the time he's done, and some of his other accomplishments -- such as reaching 23 consecutive major semifinals -- border on the surreal. Let's just hope that Federer is remembered, as well, for allowing himself to reap the rich rewards of maturity.

Look back, for a moment, at what some of the all-time greats accomplished in the Open Era:

Laver: 31 years old when he won his second Grand Slam in 1969. Pete Sampras: Bowed out with a U.S. Open title (2002) at 31. John McEnroe: Made the semifinals of the 1992 Wimbledon at 33. Andre Agassi: Despite a career-long "hatred" of the game, as he so brutally described it, reached the U.S. Open final at 35. John Newcombe: Won the 1975 Australian at 30. Jimmy Connors: Made his classic run to the semifinals of the 1991 U.S. Open at 39. Ken Rosewall: Reached the finals of both Wimbledon and the U.S. Open in 1974 at 39 -- and played his last major at 43. Pancho Gonzales: At 41, engaged Charlie Pasarell in that two-day, five-hour-plus epic at the '69 Wimbledon -- and prevailed.

More stories unfold on the women's side. On the occasion of their last meeting in a major (the 1988 Wimbledon), Martina Navratilova was 31, Chris Evert 33. Court won three majors in the year (1973) she turned 31. Virginia Wade was four days shy of her 32nd birthday when she scored her historic Wimbledon victory in 1977, and the 38-year-old Billie Jean King played all four majors -- reaching the semifinals of Wimbledon -- in 1982.

It's not so hard to fathom the residue of evolution. Players needed to keep playing in the old days, because there wasn't much money involved. The depth in today's game is astonishing, fresh talent arriving from all corners of the world. Burnouts are commonplace and the tour's schedule is absurdly long, to the point where the big issue isn't who's playing a tournament, but who's injured or pulling out.

Through it all, the remarkable Federer perseveres. In a sport often rendered tedious by baseline monotony, he's always good for a few surprises. As the tense third-set tiebreaker threatened to turn Sunday's final in Andy Murray's favor, Federer unleashed a sudden burst of finesse. He hit a tremendous backhand drop volley for a 10-9 lead, and he should have won the match on a feathery forehand drop on his second match point (Murray's scrambling get kept his hopes alive). A number of critics, including Boris Becker, chastised Murray for being too "timid" against Federer and abandoning the aggressive style that carried him to the final, but as Murray put it so succinctly, "It's a different match against Roger."

Murray was unfortunate to experience a couple of, shall we say, Roddick Moments. Unfair as that may be to Andy, people are always going to remember the shanked backhand volley that cost him the second set against Federer at last year's Wimbledon. Now we saw Murray, leading 6-5 in the tiebreaker, netting a sitter forehand with a lot of open court at his disposal. We saw him at set point again (7-6), pushing an awkward backhand volley wide. And in the end, we saw a rare display of emotion from the stoic Scot. That was one of his finest moments, I thought, allowing himself to reveal the burden of excruciating pressure back home, as well as his love for the people who support him unconditionally. "I can cry like Roger," Murray told the crowd. "It's just a shame I can't play like him."

* * *

A lot of people found it appalling that Serena Williams wasn't suspended for at least one major after her U.S. Open meltdown last September. The reason was well evident in Melbourne: Women's tennis needs her in the worst way. Not in an obscene fit of petulance -- that was a one-and-done occasion -- but in that familiar mode of fearless, inspiring play. Few players in history had Serena's mental strength, and as they gaze at the wooden rackets in their den, they can only imagine generating her brand of power.

It's hard to recall a more stunning comeback than Serena's against Victoria Azarenka in the quarterfinals. Down 6-4 and 4-0, trying to hold serve after being broken five times in the match, she looked tired, wounded and thoroughly beaten. It seemed a terrible mistake that she'd played more than two hours of doubles with Venus the day before. Commenting for ESPN2, Patrick McEnroe described Serena as "stuck in the mud," while Pam Shriver went with "shell-shocked" and Mary Joe Fernandez lamented, "She looks lost."

Only the great ones come back from that. Only the indomitable ones crack a second-serve ace at an important stage of a final against Justine Henin. People kept wondering when someone would challenge her apparent lack of movement, make her pay for all those tape jobs on her body, but she willed an answer -- even against the formidable Henin -- every single time.

"One moment doesn't make one person's career," she said in reference to her tirade in New York. "It's about all the moments you put together." She just might have learned something, too. Serena is a fun, gracious person by nature, but not in defeat. She always tended to be a tactless loser, giving no credit where it was due. She seemed especially gracious in Melbourne (admittedly, without the realization of defeat), and she'd do well to retain that tone in her news conferences.

* * *

NOTES: Some inevitable comparisons were drawn in the wake of Venus' discouraging loss to Li Na, all about Serena's killer instinct and desire, and the fact that Venus hasn't won hasn't reached a major final outside of Wimbledon since 2003. Without a doubt, the sisters have vastly different personalities. Serena is more fiery and temperamental, and history will show that she was simply a better player than Venus. But don't ever say Venus lacked a killer instinct. She's the one who led the Williams family out of Compton and into the very white, very catty world of women's tennis. You don't come from her world, intending to conquer this new one, without major doses of courage and resolve. You don't shock the world with the Wimbledon-U.S. Open double two years in a row. It just seems that Venus has stopped to smell the flowers, to express her gratitude toward the sport, with an eye on playing as long as she can. Her place in history is secure . . . It was hardly coincidence that Roddick's play came to life against Marin Cilic once he flipped his strategy into attack mode. "Hello!" Patrick McEnroe said, somewhat derisively, in his post-match analysis, adding that in many ways, strategically, Roddick still "doesn't get it." . . . Remarkable (and a little disturbing) to consider that Dick Enberg, still a beloved tennis commentator at the age of 75, is about to endure the long grind of a baseball season as the San Diego Padres' lead television announcer. He'll take breaks for Wimbledon and the U.S. Open . . . In what may be remembered as one of the most significant episodes in tennis history, Li Na and Shuai Peng led the crusade to give Chinese tennis players freedom from the suffocating demands of their federation. They were the first Chinese players allowed to train in the United States, to select their own coaches, to pocket their prize money (most of it, anyway) and to speak out against the injustice of skipping Wimbledon in favor of the Chinese National Games. They became known for insubordination, defying the restraints of tradition, but they had the 2008 Beijing Games in their favor as a showcase for their country's newest popular sport. The results have been spectacular -- Li and Zheng Jie each reached the semifinals in Melbourne -- with much more to come. Wait until the Chinese men look beyond diving, gymnastics, table tennis and badminton; that will be very interesting . . . ESPN2 was the one to watch, but here's hoping you caught some of Martina Navratilova's unabridged, dead-on commentary on the Tennis Channel. One reader e-mailed me to say, "Her commentary seems so unguarded, it almost feels like she's sitting in your house with you, drinking a beer." . . . So many U.S. tournaments are plagued by chatty, over-amped public-address announcers ("Hey, everybody, was that some great tennis, or what? Give it up for these two guys!"). Give me Craig Willis, the distinguished voice of the Australian Open. "He is the king," Willis said of Federer as he raised his arms in triumph. "He is the master."