Legal Ramifications of Antonio Brown's Growing Dispute With Raiders

When an NFL player is suspended, Article 46 usually serves as the relevant portion of the collective bargaining agreement. As has been discussed so often in recent years, Article 46 empowers NFL commissioner Roger Goodell to punish players for conduct that he deems detrimental to the league. Article 46 also authorizes Goodell to hear any appeals.

Tom Brady. Ezekiel Elliott. Adrian Peterson. The NFL accused each of these superstars of very different kinds of wrongdoing—alleged equipment tampering, alleged domestic violence and child endangerment, respectively. Despite the dissimilarity of their alleged acts, each player was punished under Article 46. Article 46 is the part of the CBA that makes Goodell, as he is sometimes called, “judge, jury and executioner.”

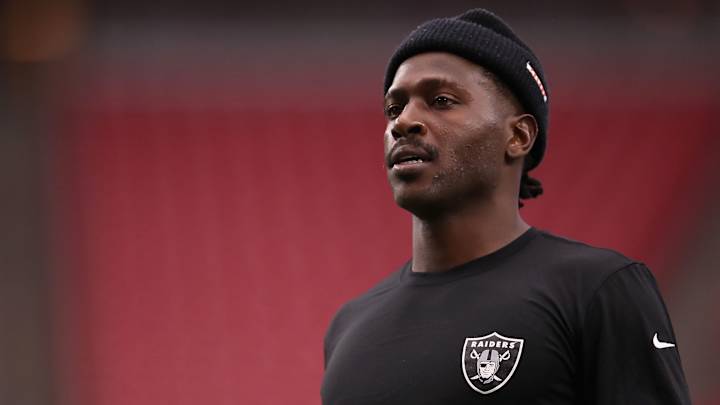

The increasingly bizarre saga of Oakland Raiders wide receiver Antonio Brown—who the Raiders intend to suspend after a heated argument with general manager Mike Mayock—leads to a less often invoked different portion of the CBA.

Welcome to a discussion of Article 42.

Article 42 concerns club discipline. It is the portion of the CBA that would become crucial should Brown challenge a suspension. It would take on even greater significance in the event the Raiders cut Brown and argue they do not owe him nearly $30 million in supposedly “guaranteed” money.

An unusual move by an NFL team to suspend a star player

Teams typically do not suspend players, particularly superstars, given that a suspension tends to weaken a team and reduce its chances for winning. Coaches, in particular, are wary of suspending their best players. In a league where merely one loss over the course of a season can dramatically alter a team’s quest for the playoffs, sitting superstars usually doesn’t make much sense.

Instead of a suspension, a team is more likely to fine or reprimand a superstar for a conduct infraction. To the extent a team wants to punish a player through playing time, sometimes the coach will sit him for a drive or quarter rather than formally suspend him.

Even though Brown, 31, is arguably the Raiders' best player and is inarguably one of the best wide receivers in football, he seems to be aggravating the team in a way that exceeds its tolerance level. Ever since the Raiders dealt a third-round pick and fifth-rounder to the Pittsburgh Steelers for the perennial All-Pro in March, and then signed Brown to a three-year contract worth as much as $54 million, Brown has been problematic.

The last month is evidence of this point: For part of training camp, Brown insisted on wearing a helmet that failed to comply with safety standards negotiated by the league and NFLPA. As authorized by the CBA, Brown twice pursued grievances over the helmet issue. As unauthorized by the CBA, Brown also missed practices and team activities.

On Wednesday, Brown surely aggravated team officials when posting on Instagram a photo of a letter from Mayock in which the general manager informed Brown that he owes $53,950 in fines. Brown added text to the phot. In the text, Brown claimed that Mayock’s decision to enforce basic rules reflected the team “want[ing] to hate” him.

The Raiders’ ability to lawfully fine and suspend Brown

The basic legal problem for Brown to contest either a club fine or suspension is that his union and the league have agreed to very specific policies concerning players’ contractual responsibilities. To that end, Article 42 contains numerous rules that players must follow or risk club discipline. Article 42 expresses these rules and fines in a schedule for club discipline.

Teams, for example, have the legal right to fine a player $695 for each pound he is overweight. A team can also impose the overweight fine up to twice per week. Alternatively, teams may fine a player $2,615 for each time he misses a curfew. As Brown has learned, an unexcused absence from training camp carries a $40,000 fine, which is imposed per day. Brown has also discovered that a missed meeting carries a fine of $13,950.

There are numerous other rules and associated monetary fines. The larger point is that in punishing Brown, the Raiders are relying on workplace conduct language that Brown’s union accepted.

Article 42 also authorizes teams to suspend players, without pay, for “conduct detrimental to the club.” Teams are generally empowered to determine which kinds of conduct are so egregious—and thus so distinct from the types of infractions associated with monetary fines—that they justify a suspension. A team can suspend a player for a period of up to four weeks.

The Raiders could cut Brown and probably avoid paying him almost the entirety of his contract

There is no indication, yet, that the Raiders intend to cut Brown. While Brown has been a headache and a distraction, he’s still instrumental to the team’s ability to win games in 2019. Unless the Raiders intend to “tank” this season, keeping Brown could pay dividends over the long haul. Along those lines, Brown might become less disruptive as he better familiarizes himself with his new employer and its work culture, and as he and his teammates play out the regular season.

The Raiders might also worry about the public relations backlash that would come by cutting Brown, a player who seems so central to the team’s plans. Even worse, Brown could then sign with another team, including an AFC West rival, and perform well for them. A suspension might thus be a better interim move for the Raiders.

On the other hand, it’s possible that the personality differences between Brown and Raiders’ leadership are so severe that they are irreparable. Raiders officials might also conclude that Brown’s continued association with the team would be so toxic that the “bad” outweighs his football talents.

The Raiders might also eye the potential massive salary cap relief they would likely obtain by cutting Brown. If the Raiders release Brown, the team could argue it only owes him a $1 million signing bonus.

Here’s why: Brown’s contract contains “guaranteed” salaries of 14.625 million in 2019 and $14.5 million in 2020. The guarantees are expressed in his employment contract through two addendums, one for each year. In contrast, Brown’s 2021 salary of $14.5 million has no such addendum and is not guaranteed.

The guarantees for 2019 and 2020 are worded with substantial protections for Brown. The team agrees that it would pay Brown even if it cuts him on account of his “skill or performance has been unsatisfactory as compared with other players competing for positions or if he is injured.

Yet the guarantees aren’t limitless in their wording. Specifically, the guarantees become “null and void” if “at any time” Brown “does not report to Club, does not practice or play with Club [or] leaves Club without prior written approval.” Further, the guarantees are voided if Brown “is suspended by the NFL or Club for conduct detrimental.”

Therefore, if the Raiders suspend Brown for conduct detrimental under Article 42, the team could attempt to deny payment to Brown of all but $1 million.

Obviously, that is the view most favorable to the Raiders. Brown, along with his agent Drew Rosenhaus, would be poised to challenge any suspension. If the suspension stands, it could serve as a predicate to the Raiders trying to cut Brown without paying him his guarantees.

The NFLPA would likely join in any fight. Even if the NFLPA questions Brown’s judgment, the NFLPA is a union. It is thus mindful of precedent and impact on future players, especially with regard to salary guarantees. Stated differently, if the Raiders can take a heated argument between a player and team executive and use it to void contractual guarantees, other teams would be more willing to impose the same punishment in similar situations.

Brown’s potential avenues to contest a fine, suspension or termination

If the Raiders’ punishments of Brown lacked without explicit authorization of the CBA, Brown would be well poised to contest the punishments through the CBA’s grievance process. Management generally can’t punish unionized employees in ways that extend beyond collectively bargained language. Employers who do so risk committing unfair labor practices and violations of antitrust law.

The problem for Brown—and, by extension, the NFLPA—is that it appears the Raiders’ sanctions are authorized by the CBA.

Still, Brown could pursue a grievance. He might have about 29 million reasons to do so.

To grieve a suspension, Brown would turn to Article 43 of the CBA. It contemplates non-injury contract disputes between teams and players. Article 43 calls for a neutral arbitrator (i.e., neither Goodell nor a person whom Goodell designates) to oversee such a grievance. An Article 43 grievance would last weeks, if not months, and involve the collection of evidence and the taking of depositions of Brown, Mayock, head coach Jon Gruden and other witnesses.

Brown’s best argument for a grievance would be that the Raiders simply have their facts wrong and, worse, are making things up to his detriment.

Perhaps Brown can prove that he didn’t miss practice or a team meeting. Or maybe Brown can show that his argument with Mayock was far less hostile than the Raiders contend and certainly not deserving of a suspension. There are rumors that the argument almost led to a physical altercation and Brown had to be restrained by teammates. We’ll see if those accounts check. Those teammates would be witnesses in a grievance.

The Raiders would try to rebut this argument by offering documentation, such as roster notes showing that Brown wasn’t at the team facility on a particular day, and by introducing favorable testimony, such as witnesses of Brown’s quarrel with Mayock who corroborate the Raiders’ account. The Raiders obviously would want to portray Brown in the worst light possible and as posing a danger to Mayock’s health and safety.

The team would also maintain that Brown’s missteps are cumulative and worsening: he began by missing practices, for which he was fined, and then (supposedly) escalated to nearly attacking Mayock. The Raiders could thus insist that fines didn’t deter Brown from worsening conduct and thus a suspension was justified.

Alternatively, Brown could charge that he was treated differently—and worse—by the Raiders than other players on the team who committed the same or similar infractions. Article 42 contains a “uniformity” clause. It demands that “discipline will be imposed uniformly within a Club on all players for the same offense.” If Brown could show that the Raiders looked the other way when his teammates committed the same kinds of infractions, Brown may be able to convince an arbitrator that the Raiders failed to satisfy the uniformity requirement. If footage from an episode of HBO’s Hard Knocks helps Brown prove that point, he could offer it.

Other possible legal remedies for Brown

If Brown were to fail in an Article 43 arbitration and if he then decided to “go the distance” in terms of challenging the lawfulness of a fine, suspension or contractual termination, Brown could petition a federal court to vacate the Article 43 arbitration award (ruling). This move would likely fail since federal law compels judges to greatly defer to arbitrators. Judges only vacate arbitration awards when they appear fundamentally unfair or appear to be arbitrarily decided. Based on what is known at this time, it seems unlikely that Brown could offer facts that prove the Raiders lacked the legal right to punish him.

Brown could also consider more quixotic avenues for legal redress. For instance, he could petition the National Labor Relations Board and contend that the Raiders punishing him constitutes an unfair labor practice. Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act prohibits employers from punishing employees for partaking in activities that advance the union’s interests. Perhaps Brown could assert that he is being punished for merely disagreeing with his boss (Mayock) about a workplace matter. Should such a punishment stand, it could serve as a precedent that damages the rights of other players. While that line of reasoning would be interesting, it would probably fail if Brown threatened Mayock in any way.

Brown could also sue the Raiders for defamation. He could insist the team falsely claimed that he engaged in threatening conduct, and that false claim damages Brown’s reputation and endorsement opportunities. As a public figure, Brown would have to prove actual malice. He could do so by proving that the Raiders knowingly published false and defaming information or had a reckless disregard for the information’s truth or falsity.

In response, the Raiders would contend what they claim about Brown is true—truth is an absolute defense to defamation—and, regardless, any claims related to a workplace grievance ought to be preempted by Brown’s contractual obligations to arbitrate.

The MMQB will keep you posted on the Brown situation.

Jenny Vrentas contributed to this story.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute (SELI) at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, where he is also a tenured professor of law.